Beautiful Scars opens with a moment of pure chaos. Musician Tom Wilson, best known for his work with Junkhouse and Blackie and the Roadie Kings, is driving to a gig. He’s stuck in traffic and nearly crossing the line between being fashionably late and being an asshole. He then realizes that the car’s out of gas. Wilson’s on his phone and he’s freaking out—not just because he feels like a jerk, but also because it’s his first day with director Shane Belcourt’s crew. The cameras roll throughout the meltdown.

Belcourt, who was in another car at the time, admits that Wilson’s vulnerability before the camera crew is a perfect introduction. “When you see Tom go through it, you see that he’s a lot like us,” reflects Belcourt. “You see that he’s going to speak very openly. He’ll break the fourth wall, which invites everybody in.” The first moments of Beautiful Scars will have the viewer hooked with Wilson’s no-BS honesty.

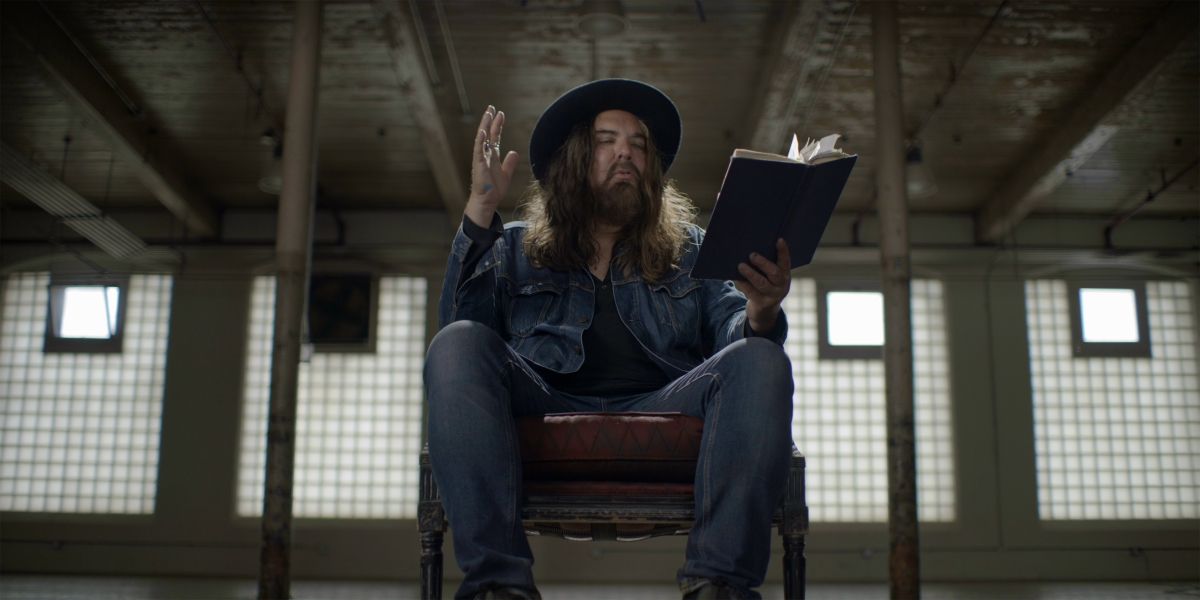

The film, which premieres at Hot Docs, adapts Wilson’s 2017, wonderfully received 2017 memoir Beautiful Scars. It lets the rocker comment upon the memories he narrates poetically yet unsentimentally in the book. Beautiful Scars largely focuses on the revelation of Wilson’s parentage, namely the discovery that his parents, George and Bunny, are not his biological mother and father. Instead, he learns that his Mohawk “cousin” Janie is actually his birth mother and that his roots are in Kahnawake, not Hamilton. Belcourt’s doc lets Wilson further explore the Indigenous identity he’d only begun to confront in his book. Beautiful Scars is a rollicking and therapeutic extension of Wilson’s memoir. It poignantly confronts the questions of identity and belonging that have exploded since its publication.

Wilson the Raconteur

Beautiful Scars draws upon eight six-hour interviews with Wilson, spread over a month. Extensive audio conversations offer context, while cinema-verité footage provides colour. The benefit of time affords the doc ample evidence of Wilson’s authenticity and knack for storytelling.

This audio base also helps, since COVID-19 interrupted production almost as soon as it began. Belcourt says he initially saw audio as a remedy amid COVID. “Whenever you’re not seeing someone on camera almost exclusively, that’s an audio-only interview,” he explains. Belcourt says that phone calls and audio interviews with Janie, as well as Wilson’s daughter, Madeline, and his friend, drummer Ray Farrugia, added substance and colour to the backbone of the project.

Tom and Janie

Belcourt initially envisioned Beautiful Scars like Eric Clapton: My Life in 12 Bars (2017) or MLK/FBI (2020), which layer audio and archive, after COVID hit. However, Belcourt admits that the limited amount of archival material left something to be desired. He says that he and his producers knew in their guts that shooting with Wilson would take the film where it needed to go.

While Beautiful Scars benefits greatly from Wilson’s on-screen magnetism as a raconteur, its strengths are the events it captures following the book’s publication. The film features emotional accounts from Janie as she revisits her painful separation from Tom. Although Janie originally declined to be interviewed for the film, Belcourt says his conversations with Tom and Madeline gave her confidence, as did the assurance that an Indigenous filmmaker would handle their story responsibly.

Janie’s presence affords Beautiful Scars the finale that Wilson’s memoir anticipates. The film follows Wilson and Janie back to Kahnawake where she signs the official registry declaring herself Tom’s mother and asserting his right in the tribe. Surprisingly, Belcourt notes that this serendipitous finale was never planned. It just happened by chance. He says they documented Wilson’s return to Kahnawake, and the rocker asked him if he could wait a few minutes while Janie signed some papers. Cue a moment of documentary gold as Belcourt asked what Janie was signing and if he could come along, which led to the film’s emotional moment in which their connection comes full circle.

Art and Identity

As Belcourt chronicles Wilson’s efforts to connect with his Mohawk roots as a musician and as a painter, the doc illustrates how he navigates his roots through art. The film includes an original score by Wilson, which Belcourt likens to the work Gustavo Santaolalla, the Oscar-winning composer of Babel (2006) and Brokeback Mountain (2005). As Wilson finds a second wind as an artist, he displays an honest reckoning with what it means to express his Mohawk heritage responsibly given his platform.

“For me, one of the key aspects of Indigenous connection is that you don’t just make a claim and then go to all the events and step in front of the mic,” explains Belcourt. “I took the opportunity to work with Tom because he never had that approach to his Mohawk identity. That was important to me. He wants to do this in an authentic way as a community member.”

Belcourt says that recognition fuelled the verité scenes, and shaped Beautiful Scars beyond a conventional rockumentary. “I wanted to show Tom engaging with his community. He is still learning and discovering what his connections are and what his colours are.”

A Story of Reconciliation

As the film goes beyond the pages of Wilson’s memoir, so too does Belcourt extend the portrait beyond the musician’s family. Beautiful Scars considers the larger scope of families fractured by colonial violence. This thread arises when Wilson reflects on an encounter at a book signing for Beautiful Scars. He tells Belcourt that a reader thanked him for his story and called him a fellow Sixties Scoop survivor. Wilson pauses and notes that he’d yet to process how his situation reflected the range of families torn apart by the settler state.

“What excited me about this project was that it was so personal between Tom and Janie,” explains Belcourt. “I wanted to let them tell their first-hand experiences and see the interpersonal dynamic, but in the spirit of Tom’s book, which was conversational from his perspective.” Belcourt credits Wilson’s family, particularly his daughter Madeline, for providing perspectives that helped illuminate questions of trauma and reconciliation. Moreover, by keeping the discussion within the family, Belcourt’s film retains the intimate scope of Wilson’s memoir without relying on talking-head experts.

“I identify with the family dynamics.”

Belcourt says that his ability to relate to the familial relationships ultimately drew him to the project. He’s always had a clear connection to his roots through his Métis/Cree-Michif father, Tony Belcourt, who served as the first president for both the Native Council of Canada and the Métis Nation of Ontario. However, Belcourt notes that his father’s activism complicated his ability to identify with his community as the family left Lac Ste. Anne for Ottawa.

“The issue of identifying with a community that is not the one that you grew up in is something that I could relate to with Tom,” observes Belcourt. “He’s trying to be authentic about who he is and allowing the complexity of Indigenous identity to include him in a modern context.”

Belcourt adds that one of Wilson’s most revealing confessions actually didn’t make it into the film due to their lively crosstalk. “He said, ‘I feel like I’m putting on this Mohawk costume.’ I was like, ‘No, Tom. That’s not the case. The reality is you’re taking off the costume that you thought you had to wear because that’s who you were told you were,’” explains Belcourt. By the film’s end, it’s evident that Wilson’s healed, whether by removing the costume or by metaphorically opening his wounds to let them mend.

“I think that taking off layers to find an authentic self is a universal,” says Belcourt. “That’s the part that I mostly connected with in Tom’s story.”

Beautiful Scars opens at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on June 17.