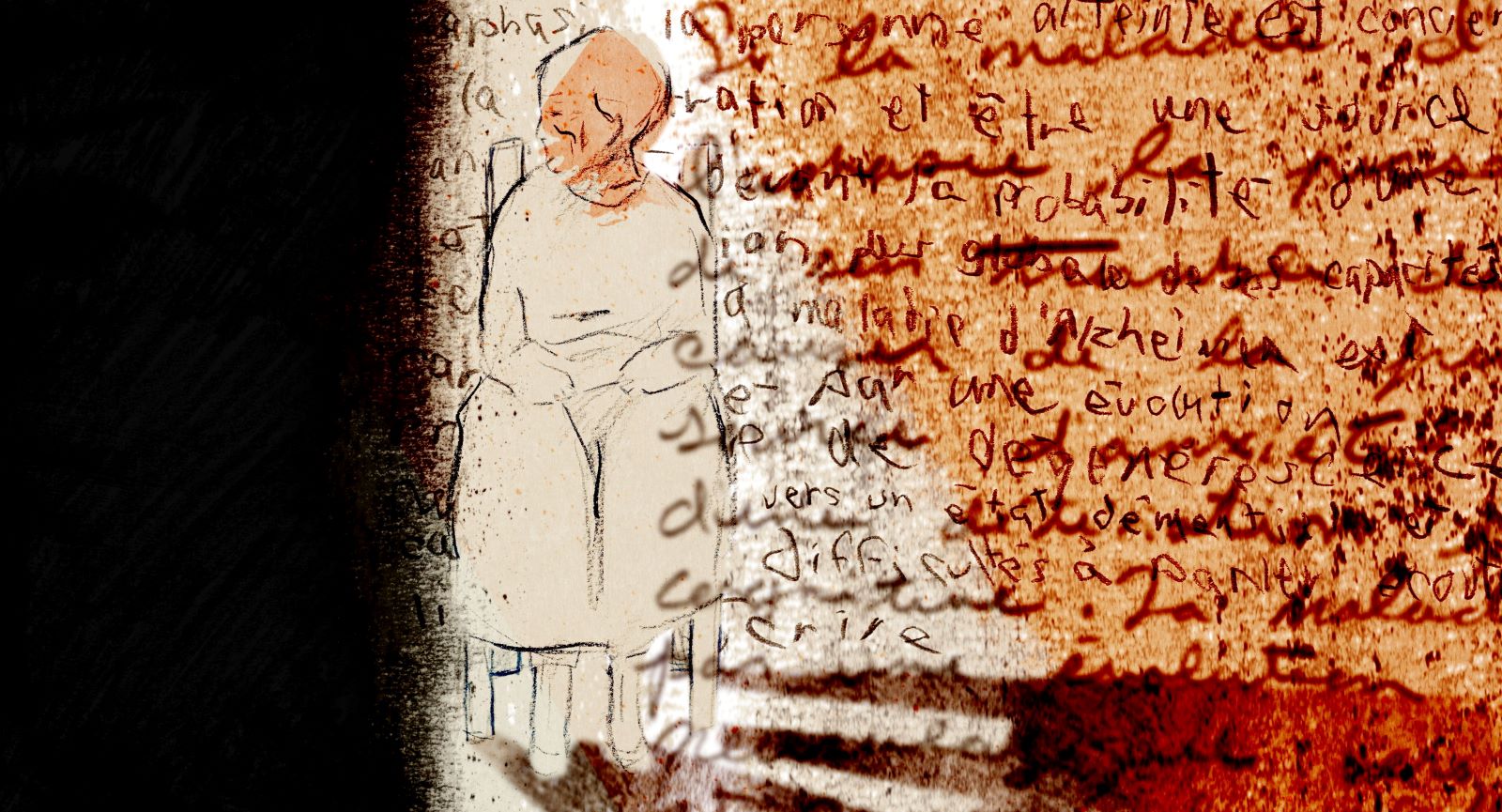

There’s a breathlessness to Aphasia, a 3 minute and 45 second short film by Montréal’s Marielle Dalpé. Her animation scatters across the screen, mesmerizing viewers while creating a deep sense of discomfort in the film produced by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). Confused text dances around the blank stares of a solitary woman seated in a room as her hands wring together, each element coalescing into a frenetic glimpse of a mind held hostage by aphasia, the neurocognitive condition that affects one’s control for language.

“Aphasia does not affect intelligence,” Clare Coulter narrates in the English version, which premieres at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. (Acclaimed French-Canadian actress Andrée Lachapelle, who passed away in 2019, narrates the French version, Aphasie.) A compassionate reminder for all of us that the confusion presented in those suffering from Alzheimer’s is not indicative of their precocity, but rather a symptom of a cruel disorder within a heartless disease.

Speaking with POV ahead of Aphasia’s debut at TIFF, Dalpé recalls a tender moment with her grandmother who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in her final years, “I was feeding her ice cream as her little snack in the afternoon.” The realization, though, of what their role-reversals meant intruded upon her: “The first time [doing this] was a violent moment, because [I’m thinking] I’m not supposed to do that, she’s supposed to feed me. But then it became a beautiful thing. She did that [for me] when I was a kid, and now I’m doing it back.”

The merciless nature of aphasia and Alzheimer’s disease brings life full circle in many ways as language seemingly becomes infantilised, and while one can’t help but feel it to be particularly inhumane, Dalpé introduces bits of humanity throughout the film, ensuring we never forget the living soul behind the illness. POV spoke with Dalpé about this condition, the significance of hands, and how she effectively created two films when she translated Aphasie/Aphasia from French to English.

POV: Rachel Ho

MD: Marielle Dalpé

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I don’t want to get too personal, but was Aphasia based off of an experience that you were dealing with in your own life?

MD: Yes, my grandmother had Alzheimer’s and aphasia. After she passed away, I did some research and there were other films that touch on the subject of Alzheimer’s disease. I never fully saw my story and her story represented: My grandmother never forgot who we were. I learned about aphasia and that was the main thing that was affecting her — the loss of language, not understanding symbols, and not being able to communicate. She was somebody that loved to read, go to the theatre, she was always writing, and going to so many book clubs. [Aphasia] was a big part of the Alzheimer’s disease that she was experiencing. Learning about it made me want to participate in the conversation about Alzheimer’s disease, [to] show another aspect of it and talk about aphasia.

POV: You mention watching other films about Alzheimer’s disease. I noticed that Aphasia is a lot more violent in tone than most movies I’ve seen on the topic.

MD: I wanted it to be aggressive, and yes, violent. What’s out there is often more — I say in French, ‘doux’ — it’s more soft. [It’s] about grieving, except it’s an acceptance of the disease. Those films really helped me and were good for me when I saw them, but there was a part of me that [thought], “But this disease is so aggressive.” It’s so hard. It’s hard for the person, it’s hard for the caregiver. I wanted to show the violence that was happening — it’s not a physical violence, it’s an emotional one.

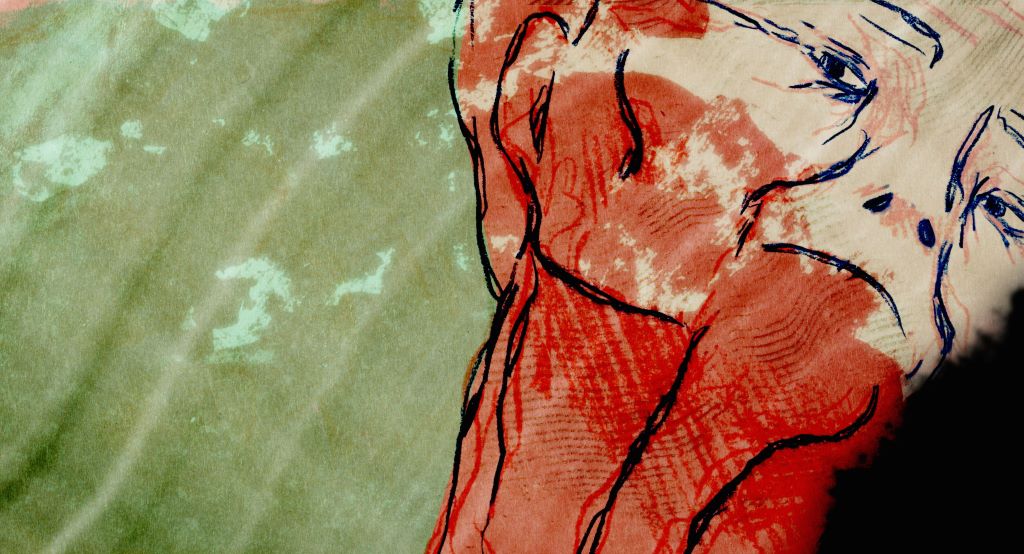

POV: I want to talk to you about the significance of hands in the film. What made you want to focus on this particular body part?

MD: Because there’s a woman on screen, people would [tell me], “You should show her suffering, show her trying to find her words.” I was really against that because my film is more of an experience for the viewer. I don’t want to tell the viewer what to feel. I want them to feel the film — the violence, the confusion, all of that. If I put emotion on her face, then I’m telling [audiences] how to feel, I’m telling them how she feels. So you’re less in the experience, you’re more in the observation.

With the hands, it’s a way of showing emotions without being direct. When you have just the hands rubbing each other, you as a viewer can interpret it however you want in that moment. You can see anxiety, desperation, just a comforting thing; it’s up to you to decide what that emotion is, but it’s still evoking an emotion. I’m letting the viewer have a bit more space to feel what they have to feel.

POV: The animation style you used is really beautiful and very effective. What techniques did you use? Was everything done on the computer or was it hand-drawn?

MD: I did what I call compositing. I use compositing as the main element for my animation, and in particular for this film. I was creating movement through textures [using] paint and crayons on paper that I photographed [Dalpé mimes fixing a camera overhead] and then her character was drawn on paper. The basis of [the film] is paper and real material, and then I put everything into the computer and finished creating [Aphasia] using that.

POV: There’s a distinct feel of polished illustrations contrasted with almost juvenile and “unkempt” sketches coming together. Was this intentional?

MD: I don’t know if I was thinking juvenile but definitely unkempt. I did some research of how aphasia evolves with people with Alzheimer’s [and] the writing would almost become childish. There’s a lot of writing in my film, and I would write certain words really well and then I would close my eyes and use my left hand to rewrite them. I’m not sure juvenile is the right term because we’re talking about old people and something that happens later in life, but it’s definitely a degeneration.

POV: I have a particular interest in language and how films are translated. There are two versions of your film: one in French and one in English. Was the film made in French or English first?

MD: The film was made with the French animation studio at the NFB and before they accepted my project I had already written and recorded the narration in French. When I arrived at the NFB, we took the recordings and reshuffled everything. Before there were even images, we edited the film, but just the sound.

When it came to the English version, we had to do it all again. Working with my sound designer, Luigi Allemano, when it was time to edit the English version, we had a base of information that I wanted in the film. I wanted the text to be very basic and informative, like information you get at the CLSC [Centre local de services communautaires, a network of free clinics and hospitals run by the Québec government]. But after that, we were starting from scratch. Both films have a very different feel. Things are not said at the same time and there’s a list of words that she repeats over and over again that is wildly different in English than in French. It was really important for me to make another sound so that it felt true and not just a translation from the French one.

POV: Let’s talk about Luigi Allemano — the sound design in your film is very evocative. You said that you didn’t want to tell your audiences what to feel, but was there a goal you had in mind for the sound?

MD: I had the idea for the sound that aphasia would be represented by glitches — aggressive sound that interrupts the narration. The other thing that I was certain of was no music. It’s only sound design. Those two things were really important, then we tried to figure out what are those glitches. At one point, Luigi wanted to try to do everything just with the voice recording [without] adding any exterior sound. That’s how we created the glitches and we found something…it all comes from the voice of Clare Coulter in the English version and Andrée Lachapelle in the French version. We didn’t want them to be digital glitches because that’s not tactile, real or grounded enough [for this] human disease. We needed to be very human with this film.