One of the most significant films touring the documentary festival circuit this fall is by the Argentine filmmaker Lucrecia Martel. Nuestra Tierra (aka Landmarks, although the direct translation is Our Land) is the first feature documentary by Martel, who has achieved international acclaim for her narrative fiction films. Her anti-colonialist drama Zama (2017) won first place in the TIFF Cinematheque poll of “best films of the decade” in 2019, having garnered near universal accolades from critics around the world. With Nuestra Tierra, she continues her scathing analysis of the history of Argentine culture, which includes–as it does in North America–the exploitation of Indigenous peoples.

Nuestra Tierra recounts the legal case surrounding the murder in 2009 of Indigenous leader Javier Chocobar by a white Argentine businessman Darío Amín. An altercation took place when Amín, who was accompanied by two former police officers, Luis Humberto Gómez and Eduardo José del Milagro Valdivieso Sassi, attempted to evict Chocobar and other members of the Chuschagasta community from their land. Claiming ownership of the land, which has minerals, and armed with a pistol, Amín shot and killed Chocobar.

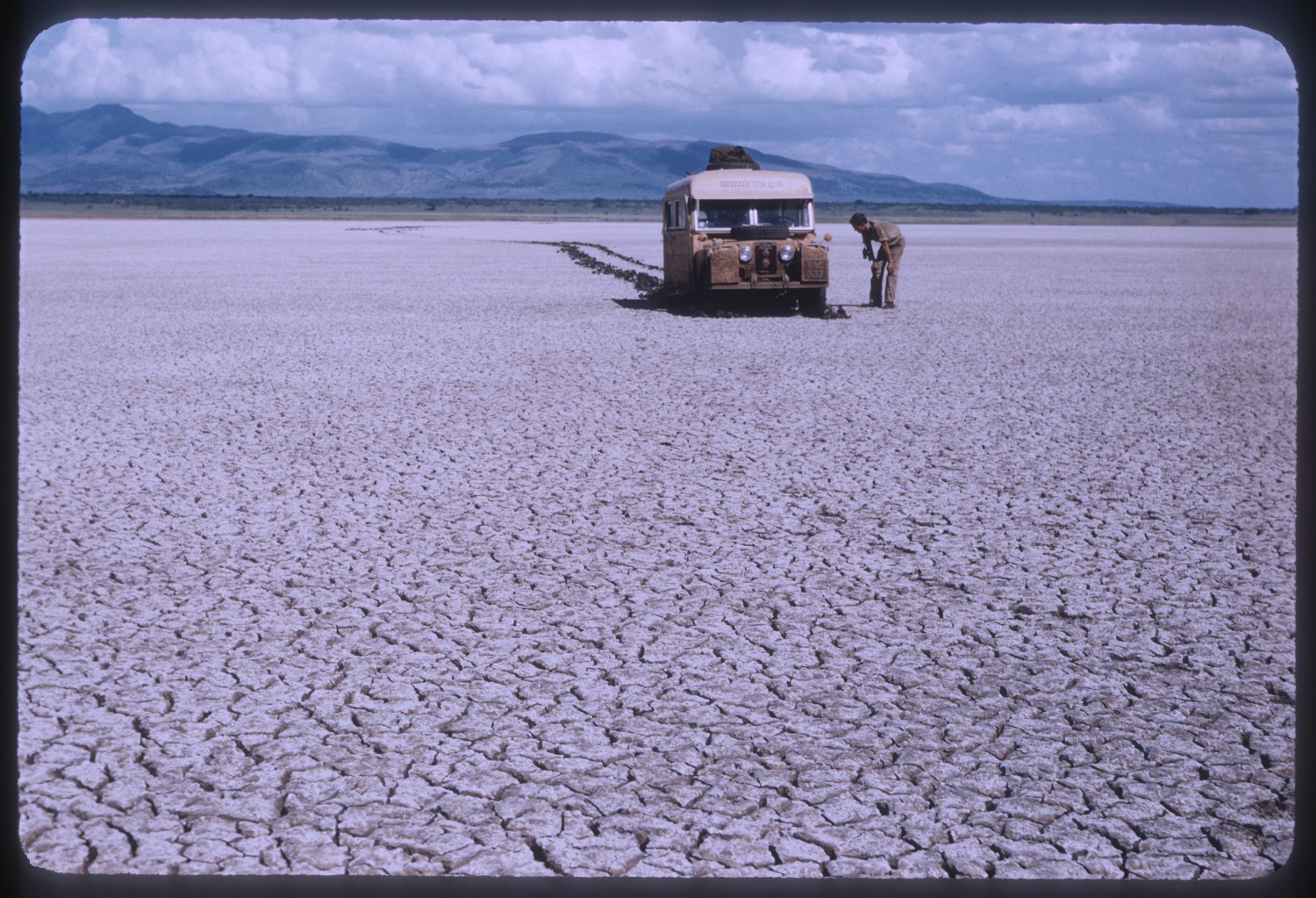

Although the event was tragic, it was fortuitous that the murder was recorded on video and broadcast on YouTube. Even with visual evidence backing up the case, it took nine years of organized protests for the judicial process to occur in 2018. Martel’s film offers highlights of the trial, the controversial footage of Chocobar’s shooting and interviews with many of the Indigenous leader’s family including a plethora of historic photos of his wife and her ancestors. Always a fine visual artist, Martel’s eye doesn’t desert her when showing beautiful shots of the land of the Chuschagasta, which remains with the community despite the efforts of Amín and his cohorts.

While the community eventually wins the case, Martel’s film shows the racism that is still in evidence in Argentina. As one of the characters says, when asked to remember what he learned in school about Argentina, “Few said that it was a country that had been inhabited by Indians, and few said that Indians still inhabit it.”

POV’s print editor Marc Glassman was allowed to submit questions to Ms. Martel via email. She replied after TIFF, where Nuestra Tierra had its North American premiere, but before her film will screen at the New York and Vancouver film festivals. Her answers are thoughtful and revealing.

POV: Marc Glassman

LM: Lucrecia Martel

POV: How did you reorient your cinematic strategies to make a sophisticated documentary instead of a narrative fiction film?

LM: Fiction trains us in the construction of verisimilitude. And that is a flashlight in the complex web of a country’s history. History is an act of will of the generations that benefit from it. It establishes an order that legitimizes the access of some to the possessions of others. History is a very particular case of fiction, the most successful of fictions. A nation is founded on myth, never on facts. I think we call a documentary any attempt to establish an order that explains what has been left out of the origin myth. In fiction, actors die and rise again. In documentary film, death is definitive. Perhaps that’s what separates fiction from documentary.

POV: You employ home photographs as an important visual motif in Nuestra Tierra. What did you want to evoke with the images?

LM: We used these photographs because when we saw them, we understood things that are difficult to convey in words. The value of the archive in this film is immense for Argentines. The relationship between Indigenous people and the urban periphery is immediately understood by looking at the photos. Internal migration in Argentina is something that isn’t discussed in school because it is the scar of the failure of all political experiments.

POV: The footage of the shooting is upsetting but ambiguous. Why did you show it many times? Did it truly help the trial?

LM: The images are as violent as the words spoken there. The history of a neighbourhood leaves traces in the language. I’m not talking about subtleties. On the day of the crime, we know that a high-ranking police officer showed up to take the camera. The Tucumán police chief was a relative of Luis Humberto Gómez. This indicates that they feared what they had recorded and preferred to make it disappear. But the community members didn’t hand over the camera until it was registered as evidence by another police officer, and that prevented it from disappearing. In the statements of the attackers and their witnesses, the violence was very clear. Eloquent in their bad faith. But what would have happened if that video didn’t exist? It was the word of one against the other. And the word of people whom history considers extinct has no value.

POV: How difficult was it to gain the trust of members of the Chuschgasta community?

LM: It wasn’t easy. We’re so caught up in misunderstandings, mistrust, and centuries-old disappointments. I think when I presented the film, something happened among all of us. Perhaps cinema has been far removed from Argentine rural issues. Argentine cinema is very urban.

POV: How does the filming of this court case further your powerful critique of Argentine society?

LM: I wish I didn’t have to give this explanation and that the film was enough. Perhaps it would be good to clarify that I’m not criticizing Argentine society. Films are opportunities to start conversations. I present image and sound shows to my fellow countrymen, to see if, together, we can invent something that makes us happier. Because if happiness is what we know… it’s not enough. It’s a minuscule happiness. There are people who hate talking about happiness as if it were the family basket, an index, something concrete. For the body, it’s crystal clear. I have a good approximation: walking without fear. If we could all walk without fear, the happiness I’m referring to would be happening.

POV: How did you achieve the extraordinary evocations of Indigenous land in the film?

LM: I think the secret lies in the way the Chuschagasta speak. The forms of speech in the hills. It seems to me that the tones of the Chuschagastas’’ voices relate to the space in a way that perhaps will be understood in the future as a document of possession.

POV: What were the storytelling limitations in making a documentary instead of a fiction film?

LM: The spectacle of sound and image is a land without limits. Isn’t it incredible to be able to say that about something on this planet? It has to be said because there are many young people who want to study law, and we need more storytellers. I think fiction is something we think we invented, and documentary is something we think happened. In both cases, we are talking about believers. But in fiction, death is a farce.

POV: Do you feel that making the film unsentimental helped to make the Indigenous cause more compelling?

LM: We sought a way to convey to the viewer in a short period of time feelings, thoughts, that took us years to understand. We discovered the Ascending Spiral [a great visual motif] while editing the film with Jerónimo Pérez Rioja in Salta. That’s what we call those moments when we understand something we’d seen and heard a thousand times, and suddenly it reveals its power. I hope I never forget those moments. Justice isn’t necessary if we listen carefully; it’s a great discovery I want to delve deeper into. I’m not talking about who’s telling the truth or who’s lying but, [I’m talking] about distinguishing what a better future holds. I had discarded most of the material that makes up this film until I was able to see it, thanks to my colleagues. That’s why we have to do things with other humans. A community is what we need; the worst in an individual can be diluted, and the best can be enhanced.