In 1990, Luben Boykov and Elena Pokova fled communist Bulgaria, saying goodbye to their friends and family, not knowing if they would see them again. “Traitors to Communism!” Russian KGB agents shouted after them as they disembarked a plane en route to Cuba from Moscow at its refueling station in Gander, Newfoundland. The young couple ran from the angry passengers still aboard the plane, leaving behind their checked luggage to confront the snow and Newfoundland’s howling winds.

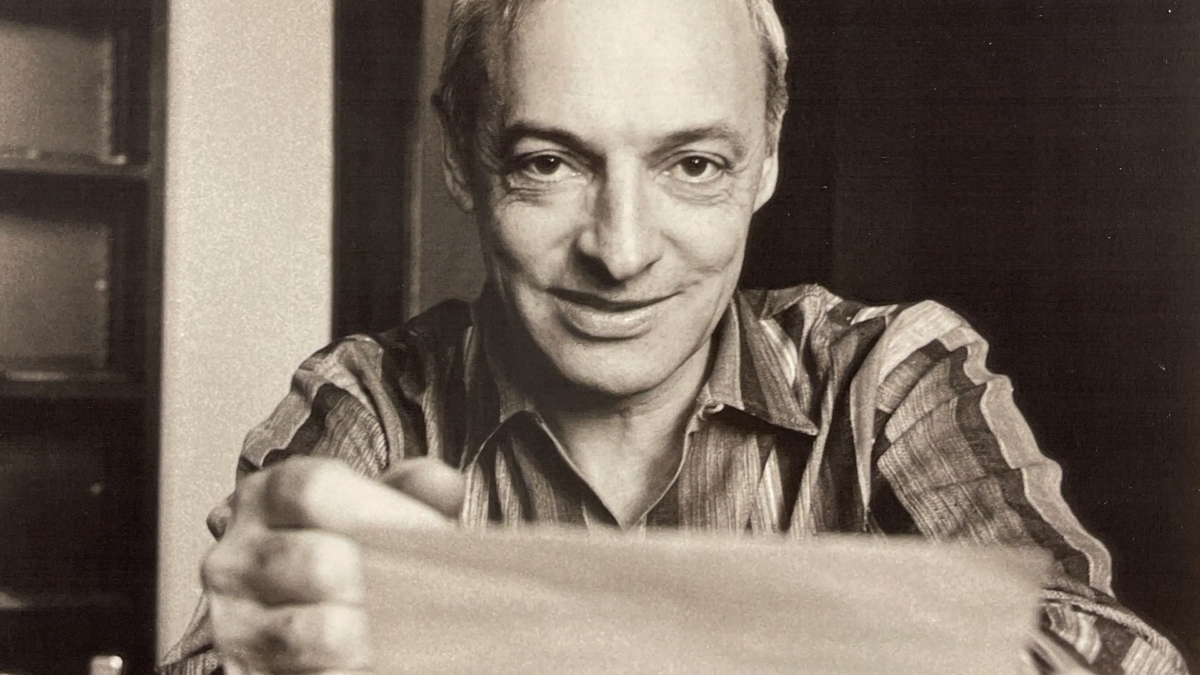

The documentary Luben and Elena is a portrait of a marriage, made by Bulgarian Newfoundland-based filmmaker Ellie Yonova in collaboration with the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). She captures their love story as it has grown and matured in tandem with the evolution of their artistic practice.

Over time, Elena and Luben have acclimatised to Newfoundland’s unique landscape and culture. They have both learned to use the surrounding nature as inspiration and material for their work. In order to feel grounded and at home in Newfoundland, Elena says she had to teach herself to love the wind, which she initially found so abrasive, even cruel.

Watching Elena paint, one gets the sense that her work is largely intuitive. It is unclear how much forethought goes into a painting before she begins, or if inspiration and self-expression entirely take the lead. Her paintings are bold in colour and brush strokes. They have a forcefulness to them that awakens the senses, much like the power of a strong cold wind. She didn’t work for a few years while her children were young, and when she started again her husband described her work as being done by someone who had been muted for a long time. A stranger once phoned Elena to thank her because her painting was the only thing “that gets [them] through the winter blues.”

Luben’s artwork, on the other hand, is more tranquil and earthy. A classically trained sculptor, Luben primarily works in bronze. When he moved to Newfoundland, there weren’t any foundries in the province for him to do his work, so he had to make one himself. Teaming up with his friend and environmentalist, John Evans, they created an environmentally friendly foundry and discovered new techniques to cast natural and local materials like grass.

Throughout the film, we see Luben collecting materials to work with, like tall grasses and rocks to be transformed into sculptures. As he has gotten older, Luben has become less concerned with the idea of immortality and permanence. He is now preoccupied with temporality, making sculptures from ephemeral materials.

“If I could make a sculpture out of air and manipulate air to the point where it could convey, at least for a brief period of time, a certain thought, emotion, idea, or feeling…this is the idea I’m moving towards,” Luben says. “The more fragile the better.”

He makes these remarks towards the end of the film, while in the hot volcanic climate of Sicily, but it is an idea both reflected and contrasted by imagery in the beginning of the film. The opening scenes are stunning shots of sculptural icebergs. (The iceberg is a natural phenomenon that, as we’re all too aware, will ultimately disappear due to human activity.) Luben is interested in manipulating the natural world with intention, whereas the iceberg is an example of how humans can shape nature, perhaps permanently, without any thought or intention.

Luben‘s approach to art is informed by his experiences, settling in different countries, adapting and embracing their different environments and cultures without feeling beholden to any particular nation. In doing so, he feels he has not had to compromise his ideals while growing as an artist.

According to Elena and Luben, it is both rare and a struggle for artists to hold their own ideals throughout the body of their work. Their fathers, who were also Bulgarian artists, introduced them to this complexity. Elena remembers her father telling her, “The sculptor is a servant of other ideals.”

“Most of the art in the Museum of Socialist Art is typical propaganda without any artistic merit,” says Luben as he and Elena stroll trough the Museum’s sculpture garden. In a secluded area of the garden surrounded by a canopy of trees is a large portrait of the Bulgarian revolutionary Zahari Stoyanov, sculpted by Luben’s father. His father was working on this piece when Luben and Elena departed for Canada, and it is his final work of art – his legacy. Despite Luben’s critical words on state sanctioned art, he sees merit in his father’s work and is moved by it.

This leads to a gap in the film as you’re left wanting to know more about their family history in relation to the history of 20th century Bulgaria, and how it has molded them as people and artists today. Luben has also done state sanctioned public art projects, but for Canada instead of Bulgaria, so you’re left to wonder how he reconciles it with his views.

When Luben’s father passed away, he created one of his most powerful pieces, two boulders stitched together with steel rope. The piece is called “My Father and I” and it symbolizes the bond between parent and son and any loved ones that are separated by great distances. The deceptively simple sculpture reflects Luben and Elena’s overarching philosophy: that one can be without a nation and still have a sense of belonging. They find belonging in each other and their family through the honesty and creativity with which they approach their relationships—to people and to art—no matter where they are. Alhough there are some missing pieces, Luben and Elena is ultimately a raw and honest look at a marriage filled with powerful art.

Luben and Elena is now streaming from the NFB.