The theory was so ludicrous it seemed almost designed to become tabloid fodder. When Randy Shilts’ epic book on the AIDS crisis (and the political response to it), And the Band Played On, hit stands in 1987, it painstakingly detailed the moral, ethical and criminal negligence of the Reagan Administration in its response to the emerging AIDS crisis.

But despite its tome-length and the rigour of Shilts’ research, the book contained one giant erroneous theory: a bad bit of misinformation that, sadly, became conventional wisdom and stained much of Shilts’ legacy.

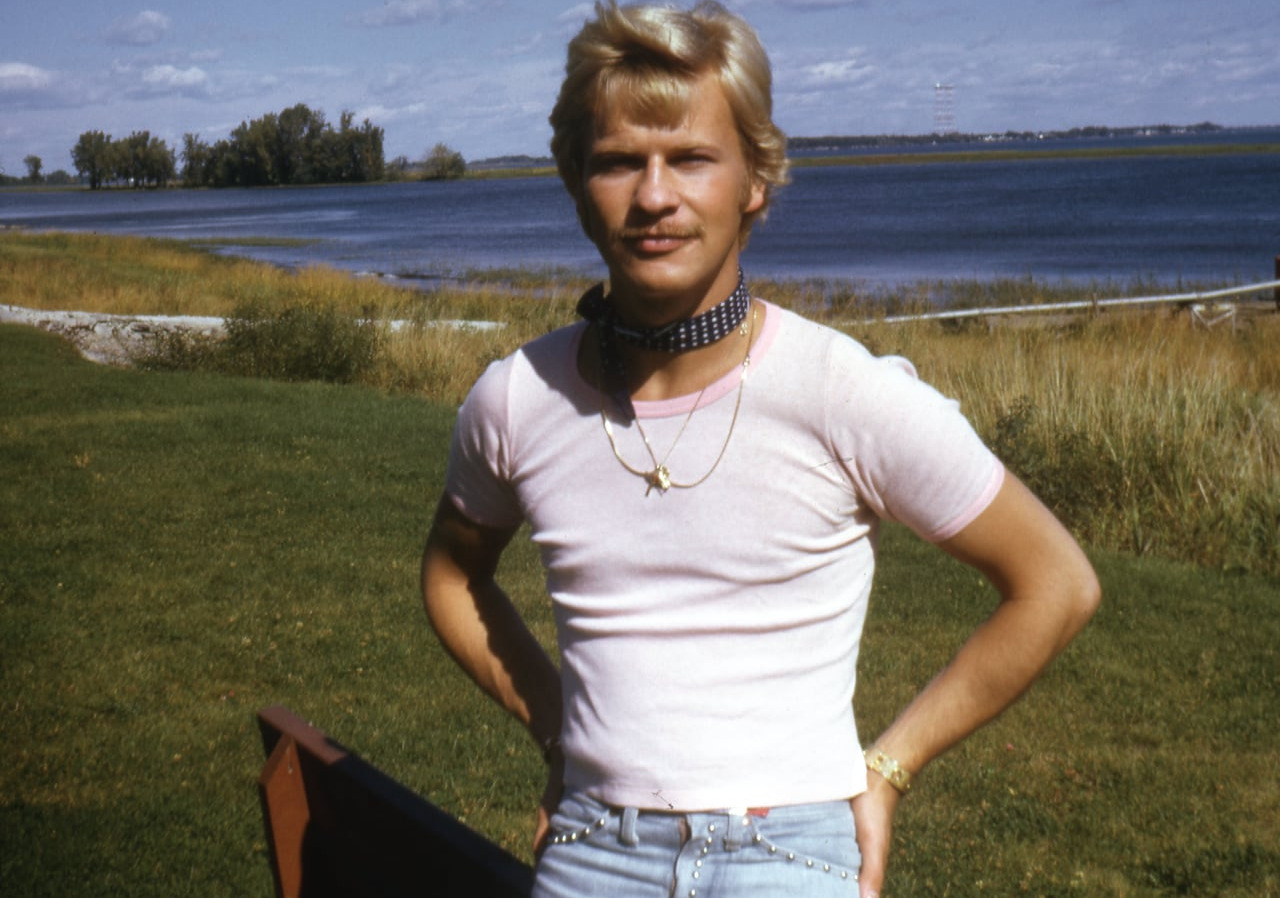

That was the idea that California scientists had identified ‘Patient Zero,’ the first person thought to have brought HIV to North America. While only a minor part of the book, the media — looking for a gay vampire of sorts who they could demonize — seized upon this idea, and stories on a promiscuous Quebecois flight attendant, Gaétan Dugas, soon popped up everywhere. Once the story made 60 Minutes, where it reached a massive audience, the utterly dubious theory had become an accepted truth about the epidemic’s origins.

The Patient Zero theory has since been completely debunked, and now Toronto-based filmmaker Laurie Lynd delves into the life and legacy of Dugas, who was so unfairly maligned after dying from AIDS-related causes. The film, Killing Patient Zero, features an array of archival footage and tells the story not only of Dugas’s legacy, but also what living through the early years of the epidemic was like. Lynd interviews a broad range of people — from Fran Lebowitz to Toronto writer Richard Vaughan to Dugas’s friend Rand Gaynor — in his exploration of the misguided theory and its fallout.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must acknowledge that Lynd interviewed me for the project and I appear in the film. (Lynd asked me because of an article I wrote for Xtra after the Patient Zero theory was abandoned once and for all.) It was a fascinating experience, because in the hours that Lynd interviewed me, I re-examined my life during those years. They were painful ones, and Lynd does an exceptional job of bringing them into clearer focus.

I spoke with Laurie for POV from his Toronto home.

POV: Matt Hays

LL: Laurie LyndPOV: When did you first become aware of the so-called Patient Zero?

LL: I was first made aware of the so-called Patient Zero when I read Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On in the late 1980’s, after I’d moved back to Toronto. Prior to that, I had lived in New York City, from 1982-1986, at the height of the worst of the AIDS years, and even though I went to fundraisers and such at Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), I think I had blinkers on for much of that time. It was reading Shilts’ (mostly) masterful book that fully woke me up to the prejudice and hatred that was inhibiting greater, quicker progress on the treatment of AIDS.

And, of course, it was in reading Shilts’ book that I first encountered Gaétan Dugas aka “Patient Zero.” I’m embarrassed to admit that when I first read the book, I totally bought into the Patient Zero story and Shilts’ hugely inaccurate version of Dugas. With hindsight, I recognize that my reaction was in no small part due to my as-yet-unacknowledged internalized homophobia, as well as Shilts’ persuasive writing, which we can see now clearly created ‘good,’ ‘respectable’ gays vs. ‘bad’ prodigiously sexual gays, i.e. Dugas. And internalized homophobia subsequently became a key theme for me, which I’ve been able to explore in three films, so far: The Fairy Who Didn’t Want To Be a Fairy Anymore, Breakfast with Scot, and of course, now, in Killing Patient Zero (KPZ).

POV: And was John Greyson’s film, Zero Patience, when you first doubted it?

LL: I had the great good fortune to meet and work with John Greyson in 1991, when I produced his remarkable short film, The Making of ‘Monsters’ at the CFC Canadian Film Centre. Knowing John and then, of course, seeing his incredible film, Zero Patience, totally woke me up to the ridiculousness of the whole Patient Zero story and to the homophobia behind the need to assign blame for this disease.

POV: What was the toughest thing about making this film?

LL: I think the toughest thing about making this film was revisiting, and in a way, re-living the ‘AIDS years.’ It is a war without an end, in a way, and prior to working on this film, I had (mostly) let it recede to the back of my mind. When I lived in NYC in the 80’s, I was an avid theatregoer (and still am) and yet I didn’t see the original production of The Normal Heart, at the Public, and easily could have. I’m still baffled by the fact that I missed it, (with Brad Davis!) and attribute that to the ‘blinkered’ view I sustained to survive those years. When I subsequently saw the brilliant Studio 180 Production in Toronto in the 2010s, I was devastated by it… I came out sobbing and wondering again why people hate us so much.

I mention this because I had the same reaction in making this film: it was deeply upsetting to be reminded of the virulence of the hatred we experienced as gays and lesbians in the ’80s and ’90s. It was similarly upsetting to relive those awful uncertain times, when so many of our friends and lovers were needlessly dying in the face of an establishment that didn’t seem to care.

POV: It was an incredibly harsh time, not just because of the disease, but the reaction to it, by members of the political class and media.

LL: Yes. Beyond the horrors of the disease itself, I realize now that to have our sex lives discussed in the mainstream press, derided as the reason we were getting — and spreading — AIDS, effectively re-shamed me as a gay man. It subtly, powerfully further complicated my sense of self-acceptance.

So it was quite emotionally devastating to live in the world of this story for the intense year and a half it took to create the film. Much of it was triggering for me: as an out gay man who lived through, and miraculously survived, the plague years, I was constantly surprised to realize how much I’d (deliberately?) forgotten about those horrible times. I felt (and feel) it has been a great honour for me to be able to tell my version of this story. As one can tell from the film, not only do I want to debunk, forever, the Patient Zero theory, but I also want to tell a contemporary audience the horrors of what homophobia wrought on my people before and during the AIDS crisis.

It still astonishes me that much of this seems to be forgotten. I don’t think I’ve ever felt as passionately engaged with my work as I have been on KPZ. But it definitely took a toll… one that isn’t the same, of course, as for those whose daily lives are touched by HIV, but one that festers. I fear that internalized homophobia, which we all battle, is an intergenerational trauma that will be with us for a long, long time, regardless of the wonderful civil liberties we now enjoy in the west. I try to tell straight people that the battle is far from over—not until I can, without hesitation, disclose the sex of my partner to a repairman in my home, say, or hold my partner’s hand in an En Route on the 401, it’s still not an equal playing field out there for LGBTQ people.

POV: One of the things I really liked about the film is the way you include the voices of women (like Fran Lebowitz). The AIDS crisis brought queer men and women together in way that I found incredibly powerful and inspiring.

LL: I was delighted to include as many women’s voices as I could. B. Ruby Rich was top of my list as I deeply admire her work (not least because I’m grateful she included me in her seminal New Queer Cinema article for The Village Voice in the 1990s). Fran Lebowitz was a long shot, but I thought, ‘Why not ask her?’ And someone like Priscilla Wald was a natural because of her brilliant book, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative. And of course, one of the many remarkable things that came out of the AIDS years was how gay men and lesbians came together in a way they never had before. I knew from the start that I wanted to make sure the voices of women were heard in this documentary.

POV: I know Gaétan Dugas’s family has never done media interviews. Did you reach out to them for the film?

LL: Save for a brief interview with [the Quebec City French-language daily newspaper] Le Soleil at the time of the Patient Zero story breaking in the fall of ’87, the Dugas family has never spoken to the press. I deeply admire their principled stand, particularly in light of the tell-all culture we live in now.

Killing Patient Zero is based on a wonderful book by Richard McKay, Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic, and Richard was in touch with the family — a delicate, slowly building trust he was able to create with them. My Quebecois producing partners reached out to the Dugas family and there was a moment when it seemed as if they might participate, but in the end, they decided to continue their silence, a decision that I completely respect.

It remains a concern of mine that KPZ will rekindle, for Dugas’ family and friends, the difficult time when the ‘patient zero’ story was first erroneously circulated in 1987. My fervent hope is that the greater good, in thoroughly rehabilitating his name, will justify the story’s re-emergence.

POV: What’s the most powerful response you’ve had to this film?

LL: I’ve been quite blown away by how many older gay men (and others) came forward at the end of each of the three screenings we had at Hot Docs, to thank me for making the film. I think the AIDS survivors (and all the lives lost) sometimes feel like a forgotten generation — and it is incredibly powerful to see our lives given the attention that this film does.

POV: Killing Patient Zero joins a number of other films, including How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger, that look back at the AIDS crisis, which for a while everyone seemed to have forgotten about. Why do you think there’s this renewed interest in HIV and AIDS now?

LL: I’m not sure why there is a renewed interest in HIV/AIDS now. I wonder if it is, in part, due to the remarkable resurgence in the popularity of documentaries, and that many queer filmmakers are recognizing how much of our collective history hasn’t been told — particularly around the AIDS years. I think, too, it is a testament to the maturity of the queer community that there is a greater interest in remembering what we’ve been through. It’s a shared history that can better unite us.

Killing Patient Zero opens July 26 at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema.