“It’s intensely personal, but it’s also about her and her work at the same time,” says All the Beauty and the Bloodshed director Laura Poitras on her subject and collaborator, Nan Goldin. The film, which won the Golden Lion at this year’s Venice Film Festival (only the second doc to do so), chronicles Goldin’s life and career as a photographer and activist with Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). Poitras examines Goldin’s recent campaign against the Sackler family of Purdue Pharma to hold them personally accountable for willfully profiting on the pain and suffering caused by their products amid the opioid crisis.

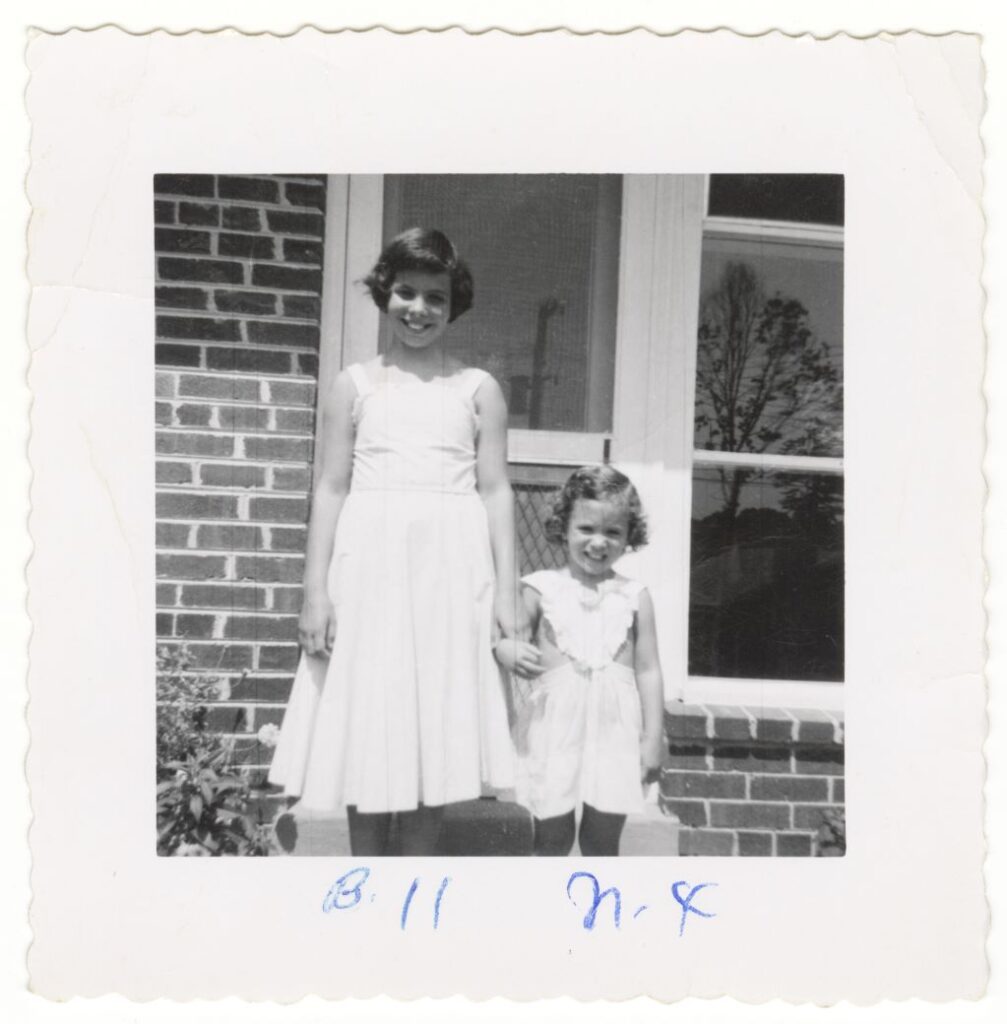

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed weaves Goldin’s present campaign through chapters that situate these activist art demonstrations within her oeuvre. As Poitras has intense conversations with Goldin about her childhood, surviving domestic violence, seeing her friends die senselessly during the AIDS epidemic, and, most significantly, watching her sister Barbara suffer through their mother’s cruelty, Poitras portrays the Sacklers’ ability to escape culpability as an extension of a social ill that continually lets powerful people off the hook.

Just as All the Beauty and the Bloodshed continues the progression of Goldin’s photographs that pass through the film in chapters about her collections The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, The Other Side, Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, and Memory Lost, the film marks the culmination of Poitras’ work as an artist. While films like Risk; My Country, My Country, and most notably the Oscar winner Citizenfour have examined the relationship between individuals and systems of power, her work has never combined studies on levels both macro and micro with such force. Art and activism perfectly collide to create one of the year’s essential films.

POV spoke with Poitras via Zoom ahead of the release of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.

POV: Pat Mullen

LP: Laura Poitras

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: All the Beauty and the Bloodshed sits well within your body of work but it also feels like a departure in that Nan Goldin is a collaborator in the film. What’s it like making a film where your subject is also a creative force in the work?

LP: Nan being an artist and having such a strong sense of vision was exciting, challenging, terrifying—there’s a range of adjectives I could use. She and PAIN began the filming of the work, so I was entrusted with the footage and to finish it. I guess that is a departure, for sure. The contemporary through line is similar to other films I’ve done, but I think the emotional depth is different. That Nan’s willing to talk about things and go places is rare with the territory that we cover. It’s intensely personal.

POV: Your films often feature this immersive verité with characters, and in this one, Nan’s voice is the backbone. Why just do audio?

LP: We had a camera crew and lighting when we did the original budget, but I never put on the schedule. It just never felt right. I thought that someday we’d do a master interview on camera, but then once I did the first sit down with just audio, I was so blown away by it. It was the section in the film [chapter 2] where she talks about, “I got thrown out of every school, every home,” and then she meets David Armstrong. I was so emotionally blown away by what happened in that interview, how intimate it was and emotional. That interview did kind of change the course of the film, because everything about her voice, the quality of the pauses, the words, and the emotion were so compelling. I’ve done this enough to know that if you introduce a camera, if you introduce lights, if you introduce another person, it would’ve fucked up something. What it would’ve up fucked was what felt to be so special in those audio interviews. We did those over the course of a year and a half.

POV: It works so well with the slideshow aspect too and her story adds a haunting quality to the photographs. What was the process of curating Nan’s work for the film?

LP: Vast does not begin to describe her archive. We made some choices about how we wanted to approach the film, and a lot of that happened with my collaboration with different editors on the film. There’s Amy Foote and Joe Bini, who I’ve known for many years, came early. He started talking about themes and chapters. We said there’s going to be this convergence of the past and the present between Witnesses Against Our Vanishing [a collection Goldin curated], the AIDS era, and the contemporary era. There’s this haunting parallel exists both in her life and in U.S. society with whatever failure of the government—a generation of people lost.

From there, we had to look at whom we chose to arrive there. It was clear that Cookie Mueller was essential. She’s one of the main people Nan photographed and David Armstrong, obviously. Once we had the individuals that we felt would ground the film, then we asked for those [photos] from the studio. It was very much a collaboration with the studio in terms of access.

POV: One thing we see in this film that we’ve seen in many of your other films are characters under surveillance. What is that feeling like, being watched?

LP: It’s been so long it’s become so normalized. Not even normalized, but I don’t remember before. It makes you think about everything. It makes you think before you type anything: are you gonna type it on your computer? Is everything being watched? It’s very pernicious, but, as a filmmaker, when Megan Kapler, a member of PAIN who you meet in the film, describes the terror of seeing somebody—there’s a man taking a photograph of her—there’s a kind of rawness to the emotion that I probably felt when I first was being followed. Now I’ve created layers of defense to pretend it doesn’t bother me anymore, but, of course, it’s incredibly disturbing.

POV: Do you think the profile you’ve gained, especially since Citizenfour, has maybe helped?

LP: There’s upsides and downsides, I’m sure. I’ve exposed secrets of governments. I don’t know that they’re happy about it, so I imagine I stay on their on their radar. [Laughs.] But on the other hand, I have a bit of protection, right? I don’t think they stopped following me, but I think they’d think twice if they were going to do something. Right now, the U.S. government’s efforts to extradite Assange are terrifying. They’re going after him for publishing he did in 2010. It just reminds me that the government has a very long memory.

POV: It’s depressing how the leaders change, but the politics don’t

LP: International politics don’t really change with the U.S.!

POV: PAIN’s campaign really inspires audiences to question institutions and follow the money. How do you navigate that while seeking funders, distribution partners?

LP: We live in a capitalist world and it’s hard to find spaces outside of that, but you also can make choices. The film is all about a complete rejection of the art-washing and whitewashing of dirty money and cultural spaces. I think we should all ask questions. If you look at how some films are being funded now, you’re going run into problems. How do you navigate that? I think it’s case by case. It’s story by story. It’s complicated. I do believe that independent filmmakers are navigating complicated distribution structures.

POV: In profiling an artist like Nan, what did you learn about yourself as an artist?

LP: It goes back to collaboration. I’ve always felt that collaboration is when you make work about people and it’s about people’s lives. Nan said, “I’d never do street photography.” Of course, she never does. She never films strangers. The people in her work are her friends, her lovers. I knew that about her work, but spending time with that, as we think about the questions around positionality and ethics, we know where Nan came from while approaching her work. It’s a great time to revisit those questions.