Geographies of Solitude is a compelling ode to Zoe Lucas, a self-taught naturalist and researcher who has lived on Sable Island, which is 300 km off the coast of Nova Scotia, for more than 40 years. Lucas is dedicated to documenting the ebb and flow of life on this remote island, from seal births to horse deaths, in detail as well as the violation of this pristine place by marine litter.

Jacquelyn Mills’ sensuous film honours Lucas’s ongoing commitment to the unique ecosystems on Sable Island via innovative eco-friendly image and sound recording techniques and poignant 16 mm footage. It invites us to reflect on our own relationship with the natural world. Geographies of Solitude had its world premiere at the Berlinale Forum and its Canadian debut at Hot Docs.

Mills is an award-winning filmmaker, cinematographer and editor from Cape Breton Island, who is now based in Montreal. Her 2017 film In the Waves, about her grandmother confronting the fragility of life, premiered at Visions du Réel and won best medium-length documentary at the RIDM.

POV spoke to the director prior to the Canadian premiere at Hot Docs 2022.

POV: Megan Durnford

JM: Jacquelyn Mills

POV: You first heard about “a woman who lives alone on Sable Island” while watching TV as a young child. At what point did you imagine creating a film about Zoe Lucas?

JM: I didn’t even realize that I wanted to be a filmmaker until I was in my 20s so it never crossed my mind that I would end up making a documentary about Zoe and Sable Island until my 30s. But I always felt really drawn to the place and the work that she does there. When I completed In the Waves, my last documentary, I reflected on the kind of work that I want to bring into the world and the kind of energy that I want to bring because we are living in some pretty chaotic times. The idea of creating a film that focuses on a sacred relationship to the natural world came into my mind and it felt really right. Immediately, it clicked that Zoe and Sable Island would be the perfect subject to explore that sort of concept.

POV: You had heard about Zoe and Sable Island for so long, I assume that you had some preconceptions. Did any aspects of Zoe or the island surprise you?

JM: Yes, everything surprised me. I didn’t have a big preconception about what it would be like to be there or to work with Zoe. I just had this very basic impression of her and the place. I was going into it very “open” to what was going to happen. Even conceptually, the way that I was approaching the film. I didn’t have an agenda. The first trip was just to experience the island. I was OK if I didn’t film anything. I just wanted to get a really clear impression of the place and the impact that it can have on you. I was completely blown away by the island and the experience of being there, and also Zoe’s work, her knowledge of the place, her generosity in collaborating with me. She ended up being in every part of the film. She guided me and pointed me to all the right spots. It was incredible, just to be there, to experience the results of her studies that span decades. Witnessing the persistent litter that washes ashore in such a majestic setting was quite disturbing. It moved me a lot and motivated me even more to put more of myself into the film and honour the work that she is doing to conserve the island and to spread her educational message.

POV: You had to deal with numerous physical constraints in order to make this film. It was your choice to shoot on celluloid as much as possible, only using digital when necessary. How did that constraint impact the film?

JM: I am somebody who works really well within limits. The limits of shooting on film help me to be present and to receive what’s around me at the moment (as opposed to filming everything I see and then figuring it out in the edit). For me, having such little film stock and ability to capture moments was actually a really rich process and it made me very creative and really fully feel like I was there on the island. I was a one-person team for the first two shoots so I had the whole set-up on me which was quite constricting.

You [had to] have the light reading ready (which could change at any moment). You have to have a rough idea of what the light is and be able to switch it just by eye if it changes quickly, which it often did. There’s blowing sand, wind and snow. I was using 50-year-old equipment from a co-op in Montreal. I was on this sandbar and if one little piece of this equipment [stops working]–if anything happens, if sand gets in it–that’s it. I can’t get more gear. I can’t order more film if the film gets compromised. There were moments when I was about to film, and I realized that a full battery was suddenly dead because it was so cold. So I would have to find a place to put all the gear, walk all the way back, get another battery, go back to the spot–and then it’s all different, right?! But the journey of walking with the battery–to me, that was the film. As I was walking with the battery, I would say: this is the process and the things that I am seeing and feeling.

POV: Did you have a backup plan?

JM: I did have a digital camera. I didn’t expect to use it. But in case I was going to use it, I got one that I could shoot at night because Zoe had mentioned to me that the stars on Sable Island are remarkable. I ended up using this camera quite often at night. I would film all day, clean the gear, prep it for the next morning and then go out for hours at night. Because it was a nighttime-sensitive camera, I could see so much through the camera that I couldn’t see with my own eyes. I was so enthralled with that process that I kept going out at night and filming more and more.

I had no idea how I was going to open the film. When I got to the edit stage, I did many simple assemblies, and one of these was the nighttime material. While editing, I was staying at a place in nature. I was under the stars one night and it struck me that, yes, this is the exact mood that I would like the viewer to enter into this film: the feeling of being under the stars. I put it [nighttime footage] there at the beginning, and it never left!

POV: Apart from this film, you have directed two others about the fragility of life and searching for meaning in the natural world. What is your personal rapport with the natural world?

JM: When I spend time in the natural world, it gives me the space to reflect on my own relationship with nature and society and the energy that I want to contribute to the world. It is an essential part of my well-being and my artistic practice. I’ve devoted my work—and I’ll continue to devote my work—to that sense of how we can heal the natural world and ourselves through the world. It is very dear to my heart. I have never considered myself a political filmmaker. I really appreciate environmental documentaries and I think that there is an important place for them in the world right now. But for me, personally, I feel that my contribution is more about an experiential relationship with the natural world. It is about a sensorial experience and immersing yourself in a remarkable place and then having a bit of stillness and quiet for these deeper instincts to emerge.

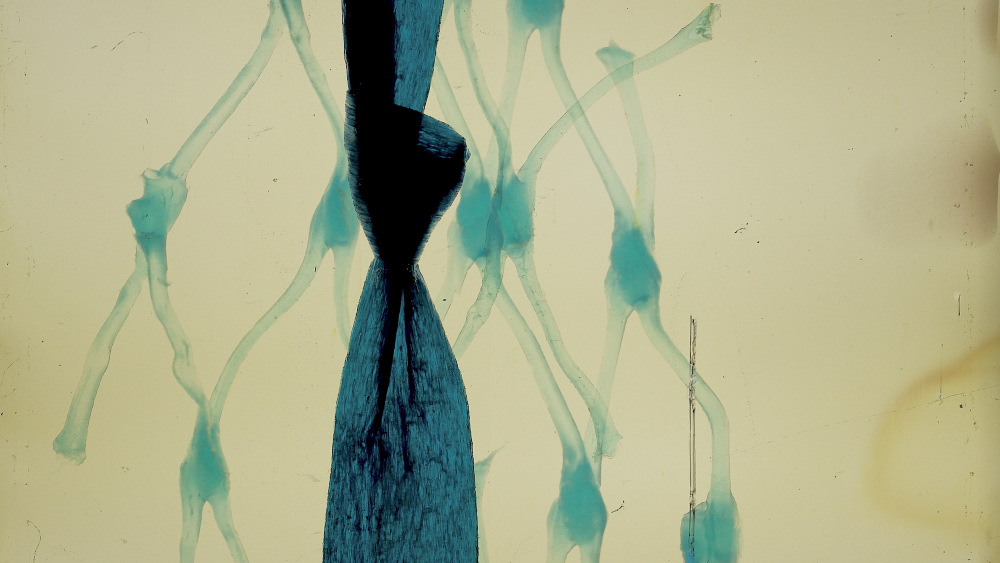

POV: Geographies of Solitude features numerous experimental image creation techniques, such as exposing film in starlight and developing film in seaweed. What was the rationale for employing these techniques?

JM: The inspiration was “How can the natural world make a film?” How can I draw from as many elements in the natural world as I could think of to create a film? It was almost like its own project. Whenever I wasn’t on Sable Island, I was working on those experiments (during three artist residencies in Iceland). I was quite impressed by how many actually turned out, when you process with organics you would think it would be pretty unstable. Also, I was splicing real-life elements to film. I worked with Frame Discreet in Toronto and they were able to scan these pretty bulky film splicings (that could have done some real damage to the scanner!). There was a lot of serendipity and a lot of searching for more ways to explore the many layers of the subject matter in this place because I am so impressed with Zoe’s commitment to the natural world that I was trying to find as many ways as possible to honour that.

POV: Goldenrod sprout, snail, juvenile worm and beach pea are listed in the music credits. Can you explain?

JM: That was done with electrodes that were contacted to living organisms. Electrodes record their electric currents. From that pattern, we created a MIDI pattern. Which note is played and the length of the note, overlapping of the notes: that is the pattern of the electric current of a living being. Also, throughout the film, you can hear the footsteps of different invertebrates. As they climbed over the contact mic, I could record their “footsteps.” It was a total accident the first time! Then I started doing it on purpose after that point.

POV: Could you tell me a bit about how you and Andreas Mendritzki collaborated on the sound design for this film?

JM: Andreas and I have been collaborators since film school [about 15 years]. He helped me to do many things on Sable Island. I would record surround sound while I was there at each setting and I would do my own foley because I was shooting on film so a lot of this stuff was not synced. So I had this big sound bank of Sable Island (including sounds recorded using contact mics and hydrophones) and it was all pretty much organized because there was so much material. As I was editing, I couldn’t help but draw from the sound bank. I am so passionate about sound.

It actually helped me a lot with the structure of the film because the sound would “fill in” the scene. Doing the sound design as I’m shooting is actually part of how I edit a film. Andreas really helped to bring the film further in a lot of ways, technically and creatively. Something that really surprised me when it screened in Berlin—and it was the first time that I saw it with the completed 5.1 sound design—I really felt like I was on Sable island! Feeling the wind and the sand and the “edge” [you feel like you are on the edge of the world when you are there] was a beautiful surprise. The winds are coming at you from across the ocean, and you feel it.

POV: Zoe plays an invaluable role; collecting, categorizing and recording everything from seal births to microplastic contamination on Sable Island. Who will take over this role once she is longer able to?

JM: That’s a great point and it crossed my mind many times. It will have to be a team of people! I don’t think that any one person who could fill Zoe’s shoes. She is the president of Sable Island Institute. I think her goal is to continue the brand audits and a lot of the studies that she started with the team at the Institute. The goal and the dream is to continue that work into the future.