“We consider ourselves a country that is big on equity. Well, not when it comes to sports,” says The Pitch director/producer Michèle Hozer. The Pitch, which screens in the Windsor International Film Festival’s Canadian competition after winning an audience award at Calgary, tells the story of the push to create a women’s soccer league in Canada. The documentary follows two-time Olympic medalist Diana Matheson as she seeks to translate the enthusiasm for women’s soccer she’s experienced on the world stage into professional opportunities for fellow players at home. It’s no easy task, though, as Matheson’s “Project 8” takes shape to establish women’s soccer teams in cities across the country.

Hozer (Sponsorland, Sugar Coated) admits that she doesn’t come to The Pitch as a soccer fan. She calls herself the “Ted Lasso” of the group and notes that the resilience of Matheson and other women easily drew her to the project. But like the American football coach hired for a British soccer league on the hit sitcom, she finds common goals and experiences to connect.

“My point was that it wasn’t going to be a sports doc,” Hozer explains. “It was going to be a more universal story, a bit of a David and Goliath story of these women trying again to get their rightful place. It should have been theirs a long time ago.”

Hozer says she got a tip about Project 8, now the Northern Super League (NSL), from executive producer Nathalie Cook, who joined Matheson’s campaign as a consultant following her work at TSN and Quebec’s sports broadcaster RDS. Matheson’s grassroots push with players like Christine Sinclair, Erin McLeod, Amy Walsh, and Rhian Wilkinson easily piqued a filmmaker’s curiosity. “Why is it on the backs of these former players to be the ones to put together a league?” asks Hozer. “As opposed to, say, starting something new, it was looking at decades of the fight of these women. The film is more about gaining justice than actually starting something new.”

The Pitch follows Matheson and business partner Thomas Gilbert beginning in November 2022 as the campaign gets off the ground. Conversations with prospective business partners raise the not-altogether new misconception that nobody wants to watch women’s sports. They do, though, and Matheson and company have the receipts to prove it. The audience for women’s sports experiences a “record shattering surge” these days. It makes good business to invest in women’s sports. But bites are hard to come by.

“When a men’s league starts, it’s normal to say it’s going to take five to ten years to see a return on investment,” notes Hozer. “But they’ve always kicked the ball down the court. There are naysayers in every industry. To Diana’s credit, she closed her ears to that noise and went to people who actually believed in what she was trying to do.”

The Pitch observes as franchises set up shop in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Halifax, and Calgary, gradually inching towards the minimum need for six teams to realistically establish a viable league. As Hozer follows Matheson, Sinclair, and other players, the conversations about the league have familiar echoes. Former player Amy Walsh, for example, shares how her career with Canada’s national team abruptly end when she became pregnant. She tells how the onus was on her to provide childcare, effectively putting her in an either/or position regarding her roles as player and mother. Soccer in The Pitch serves as a catalyst for wider conversations about equity.

“I always thought, what if you remove soccer player or athlete from the equation and you put a lawyer, filmmaker, doctor,” says Hozer. “If a female lawyer has done really well, and you tell the person, ‘Guess what? There’s just no room. No one wants women lawyers, so you’ll have to practice your trade outside,’ we wouldn’t accept it. And yet there is this myth that no one watches women’s sports and we accept to these women having to leave the country to pursue their dreams.”

It’s something to which Hozer obviously relates as a director, producer, and editor with the film industry’s own sluggishness towards opportunities for women. She points to festival line-ups in which she’s been included that trumpet gender parity and asks why that’s not a given. “We are half of the population, but [parity] is always championed as our goal and we’re not always meeting it. You see the parallels in trying to fight for your space: even though it’s owed to you, and you work just as hard.”

She relates Walsh’s situation to her own experience juggling motherhood with work, noting the need for changes in workplace attitudes. “Today, things are a bit different. You see babies on the field at the NSL. I think in our industry, it’s a bit the same: When I had a family, it was very important that I create my own space, my own room, so I can have both family and work,” says Hozer.

“Many times when it was time to go for the ‘daycare dash,’ especially as an editor, there were filmmakers beside me who said, ‘What do you mean you’re leaving at 5:30?’ My rule was that from 5:30 to 8:00, sorry, I have to do the mother thing. I have to take care of my kids. If they [colleagues] want to stay later, we’ll do it past 8:00 and then get my time afterwards. Many times they said are sort of like, ‘Maybe we don’t need to [keep working]. Maybe tomorrow we can pick it up.’ Or they would accept it. But you almost had to fight for that space whereas men don’t have to do that.”

However, one has to ask Hozer another question on the filmmaking side while telling this story: If it’s assumed that nobody watches women’s sports, is it hard to pitch a documentary about women’s sports?

“I think like Diana, there’s people who totally get the story right away and understand the value and understand the universal story behind it,” says Hozer. “And then there are others who just roll their eyes and say, ‘women’s sports’ and they’re not interested, or they separate sports from arts. If it’s done properly, you can go beyond the world of sports, and women can see themselves in the story despite coming from different areas of the world. And I’ll tell you, TVO got the story right away.”

Besides TVO, Ontario’s public broadcaster, The Pitch holds further proof that there’s good business in supporting women’s sports. The film features a partner in Canadian Tire, which certainly makes it unique with corporate investment in the Canadian documentary landscape. “Canadian Tire came in and gave us a distribution advance and some money for the film and for the impact campaign,” says Hozer, who notes that public bodies like TVO and the Canada Media Fund were on board with Canadian Tire’s participation.

“Canadian Tire had no editorial control. They were just happy to be part of the initiative,” adds Hozer. The Pitch has sponsors like Toyota, Coca-Cola Jumpstart, and Canadian Women in Film helping to drive the impact campaign, which coincides with the film’s festival run and, notably, the first year of finals for the NSL. “Diana put together the league, but I don’t know if younger audiences understand the complete struggle that she went through or the history behind how many women at different levels help build to where they are today. I think that is really important for doing this impact tour.”

Over the course of raising the money, however, Canada women’s soccer made headlines as the 2024 Olympic team found itself embroiled in scandal when it was discovered that coaches used drones to spy on the New Zealand team. (It’s been reported that the players didn’t view the footage.) The Pitch captures that scandal as another example of the players’ commitment to representing Canada as they prove to the world that they’re not cheaters but dedicated athletes who earned their spot among the best in the world.

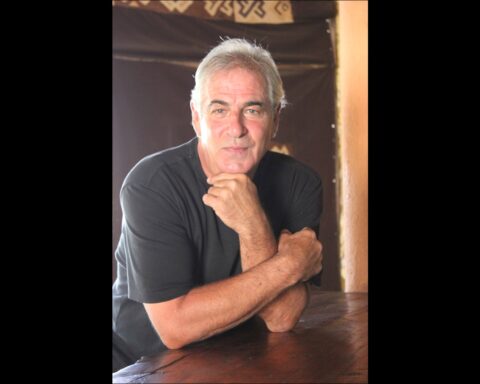

One of the figures embroiled in the scandal is John Herdman, the former coach of Canada’s women’s team from 2011 to 2018—covering Olympic bronze medal wins in 2012 and 2016—and a major supporter of campaign to establish the women’s professional league. Herdman appears in interviews in The Pitch, but Hozer notes that they predate the Olympic affair.

“It was right in the middle of the political upheaval at Canada Soccer,” notes Hozer. “There was change of leadership, and we were a bit of a pariah. Our cameras weren’t allowed in. John was there and we did an interview with him. Then a year and a bit later, this scandal happens. By fall of 2024, we understood John Herdman being involved in this story.” Herdman received an admonishment from Canada Soccer earlier this year, while coaches directly involved in the Olympic case swiftly received tougher sanctions.

While the scandal adds another hurdle for Matheson and company, the women in The Pitch generally stand by Herdman and his contribution to soccer in Canada. “What I think of John Herdman, what I think of the scandal is really not very important,” says Hozer. “It’s what these women believe, and I let them speak to the situation and speak to him. It was important for him to be part of the documentary because of his history of bringing that team where they were.”

While one could see the outcome as further evidence of men getting off easy while women are left to answer for them, Hozer instead looks to the pattern of perseverance, which pays off as the dream for the league becomes fully realized. “Diana could have done the route of opening an expansion team within the NWSL, the American League, but she chose the hard route. She wanted something here in Canada for Canadians to champion Canadian values,” says Hozer.

“Given where we are today, I think the world caught up to her. She created a league for women by women here in Canada. It’s a whole ecosystem of money staying within Canada, and isn’t this what we’re trying to champion now in 2025: to keep all the talent and all the resources and the trade within the country? She didn’t know that was going to be a priority when she started it, but the world has caught up to her and they see the value in what she has done.”