I don’t know where to begin with Errol Morris. It turns out that the filmmaker, one of the top artists in his field and a delightful conversationalist, doesn’t really like it when you call his film a documentary. “Why do you use this word constantly?” he asks during our conversation about his new film The Pigeon Tunnel.

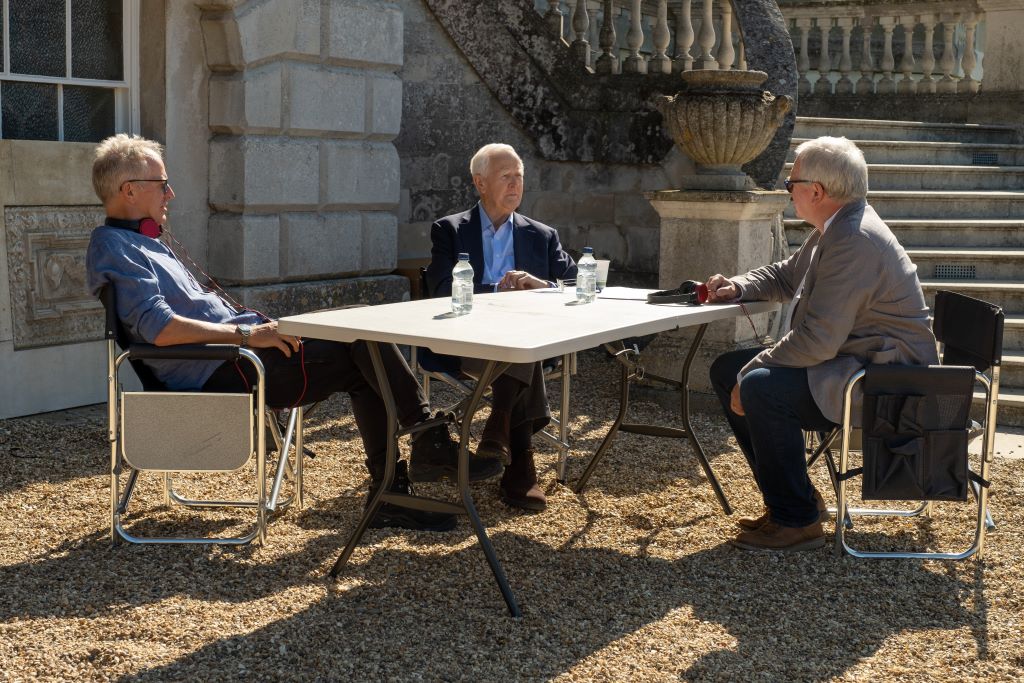

For context, I was asking Morris about a production note that said he had a crew of 100 people when filming at Wrotham Park, the estate of the late David Cornwell, better known as author John le Carré. I noted that a crew of such size was unusual for “documentaries.” (I also referred to Cornwell’s abode, which was used as a stand-in for Buckingham Palace on Netflix’s The Crown, as a “house,” so Morris might have been highly attuned to semantics.)

“What I do, they’re not strictly speaking ‘documentaries.’ They’re hybrid movies. They have elements of drama,” explains Morris. “I’m the progenitor of the kitchen sink approach. There’s interviews—very stylized interviews—shot with multiple cameras and mirrors. There’s drama. There’s found footage. There’s quotations from the various movies that were made from his novels. You name it.”

That approach obviously requires a lot of hands and it shows. In true Morris fashion, The Pigeon Tunnel has everything but the kitchen sink and is the better for it. While The Pigeon Tunnel adapts Cornwell’s book of the same name, the writer’s conversation with Morris evokes a desire to leave a final testament, much like the filmmaker’s interviews with former secretary of defense Robert McNamara in the Oscar winner The Fog of War (2003).

The Pigeon Tunnel marks Cornwell’s final interview and draws upon four days in which Morris sat down with the author. “He scared me—the daunting prospect of interviewing such a man,” admits Morris. “Ultimately, I really enjoyed it.” The film offers a meeting of the minds between Morris and Cornwell, and, documentary or not, it’s a pleasure to watch as the director and interviewee clearly hit it off. Their singular voices combine to create an adaptation of Cornwell’s memoir that speaks to their distinctive approaches to storytelling.

A Meeting of the Minds

The film, which debuts in theatres and on AppleTV+ on October 20th after premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this year, explores Cornwell’s life and work with inquisitive vigour. An engaging conversation between Morris and Cornwell forms the spine of The Pigeon Tunnel, named the author’s childhood memory of a posh Monte Carlo hotel that had a narrow passage through which pigeons would fly and emerge for patrons to shoot on the other side. The film weaves between the amiable, probing chat between Morris and Cornwell, while actors portray the “well-lunched gentlemen” who take aim at unsuspecting pigeons in a meticulously edited opening sequence that foregrounds the act of storytelling in Cornwell’s tale.

But don’t call these dramatic bits “re-enactments.” Morris doesn’t like that term, either. “I’m not re-enacting anything,” he says. “I’m just telling a story: a traditional movie story interlaced with interviews.”

As Cornwell converses with the director through the Interrotron, the device that Morris devised to let a filmmaker interview a subject “face to face” while capturing eye contact for the camera, it’s clear that a straightforward talking heads-style interview piece wouldn’t do the author’s story justice. “A lot of these are elaborate constructions involving green screen involving computer graphics,” Morris notes on the film’s cinematic touch, adding that he storyboards his scenes and works with a production design to get the story right. “No pigeon was killed in the making of The Pigeon Tunnel. When you see pigeons being blown to smithereens, this is done with computer graphics. It’s an elaborate production involving, I think, a lot more than you would see in a traditional drama.” Cornwell’s tale, like the espionage books The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Solider Spy that make John le Carré one of the world’s most popular novelists, is one of twists and betrayals.

A Story of Betrayal

As Cornwell tells Morris about his the mother who walked away from the family when he was five years old and a father who served time in jail for fraud and left the family in perpetual debt, the conversation frequently circles back to betrayal. It’s perhaps inevitable, given how much double-crossing is part of le Carré’s spy tales. But the family story is essential material, as Cornwell shares that his father, Ronnie, offers inspiration for the con artist Rick Pym in his 1986 novel A Perfect Spy. Other memories include the time Cornwell repaid his father’s debts by betting on horses, winning back his dad’s losses, and clutching a big bag of money on the train en route to reconcile matters with a bookie. Cornwell’s reflections about his father may seem cold, but they illuminate his stories about civil servants hardened by experience.

Later in the film, though, Morris tells Cornwell that one of the producers has a request: They want him to talk more about betrayal. The theme permeates the film, though, as John le Carré delivers one bestseller after another and Ronnie devises harebrained schemes to get his son’s money. “Betrayal certainly is a theme that runs through the entire movie, but there’s a lot of other stuff that is really not betrayal,” observes Morris. “His thoughts about the history of truth, about good and evil. If I got my back up about this whole emphasis on betrayal, it’s not because I don’t think it’s an interesting theme in general or an interesting theme in his life. I do think it’s an interesting theme in his life. But there were other things that interested me as well.”

The Credit Balance

Cornwell suggests that he found ways for Ronnie to repay him, though. He tells Morris during their conversations that “childhood is the credit balance of the author’s inspiration.” Morris relates to the writer’s credence, noting that he sees echoes of his own life, particularly family tragedies, throughout his work.

“I often think of my mother’s personal tragedy,” Morris says. “My mother was one of the most gifted people I’ve ever known: an extraordinary musician, graduate of the Julliard, almost a doctorate in French studies at Columbia. My father died when I was two years old. I don’t have any memory of him at all. What I do have a keen memory of is my mother’s struggles over the years to raise a family, my brother and myself, and a person who was always intellectually engaged in so many different things. I would like to be more like her if anything,” he explains, evoking a much different relationship with his family than Cornwell.

“My brother died suddenly, as did my father, of massive heart attacks in their forties,” Morris adds reflectively. “The sudden appearance of death in life and this odd probabilistic universe where anything can happen and everything does happen, that has been a central fixture in my work and in my life.”

Interviews vs. Interrogations

The theme of death is obviously present throughout The Pigeon Tunnel as it presents ghostly images of the author who died in December 2020. When it comes to the questions that can’t be asked in a follow-up, though, Morris doesn’t have any regrets. Both he and Cornwell knew the interviews for The Pigeon Tunnel would be the author’s last. “In the interim, since this interview was done and David died, there are all of these stories about his sex life, which are really not part of this movie,” Morris says, gaining momentum. “Was I interested in his sex life? I really wasn’t. I assume he had one. That’s okay. But did I have to make the movie a kind of exposé: ‘Did you do this? Did you do that? Are you lying to me? Are you telling me the truth?’ No! It’s not something that was at the centre of what I wanted to do. So kill me!”

Morris’s line of rhetorical questioning here echoes one part of The Pigeon Tunnel in which he and Cornwell debate what distinguishes an interview from an interrogation. The conversation playfully circles back to the interview process as Cornwell, displaying his years of wisdom gleaned through working in British intelligence, decides how to play his cards. But Morris understands that Cornwell’s diligence in selecting his words carefully tells a story of its own, particularly when paired with images of BBC adaptations of le Carré books, like The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, starring Richard Burton as Alec Leamus. (“One of the greatest performances I have ever seen on film,” Morris says.) Or Alec Guinness as George Smiley in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People. (“The perfect quintessential John le Carré figure,” says Morris.)

The Thin Line Between Disappointment and Satisfaction

“What’s going on here is that you have this combination, which I think is the essence of David’s art, of his biography, his personal history, the history of the world—the fact he’s sitting in Germany in ’61 and the Wall is about to go up,” observes Morris. “It’s one of my favourite things in the movie, the connection between these scenes in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, the movie, and actual raw documentary footage from the Berlin Wall itself, a parallel between this piece of fiction and reality. That tension is there throughout everything he did. That’s the fun part of moviemaking—being able to make connections, tell stories, and tell stories in a different way than what you might expect. I like the movie. I don’t usually like what I do, but I think there’s something interesting there.”

When prodded about why he often doesn’t like his movies, Morris admits that it sometimes simply amounts to disappointment. “I always think I could have done a better job or a different job,” he notes. There is however, one exception: “I was happy with The Thin Blue Line [1988] because I stumbled on a case by accident and did the impossible,” he says of his landmark true crime film that proved a breakthrough for non-fiction storytelling with its hybrid approach. “I got a man out of prison and showed that the chief prosecution witness against this man was the real killer. Who gets to do that, ever?”

Looking back at The Thin Blue Line and the innovative approaches to film that it’s inspired, Morris, like David Cornwell, finds something to be admired in having such a distinct voice. “I still like to think that I do things differently than than other documentarians, other filmmakers,” he observes. “I like to think that I’ve evolved my own personal style and what a big surprise! I kind of like it.”