Fifty years ago, in October 1970, all of Canada was gripped by events unfolding in Quebec. The FLQ (Front de libération du Québec), a violent separatist organization, kidnapped the province’s Deputy Premier and the British trade commissioner. As these events became national news, the FLQ emerged as a major part of a much larger struggle going back to Quebec’s “quiet revolution” of the early Sixties. A brutal element in what was otherwise a peaceful growing separatist movement, the FLQ had a longstanding impact on language and politics within Quebec and Canada. The federal government’s response to the FLQ’s actions, the only peacetime imposition of the War Measures Act, suspending basic human rights in Quebec, brought the October Crisis into the international spotlight. And it brought the phrase uttered by Trudeau “Just watch me” into the increasing linguistic and political divide between Quebec and the rest of Canada.

For many anglophones inside and outside of Quebec, the October crisis represents the first time many considered the unequal treatment of French Canadians within the country. Through their writing and manifesto, the FLQ further shifted the public French language to something more attainable and less formal. It was part of a growing movement of artists and intellectuals emerging after the quiet revolution that changed perceptions about Quebec’s French language. This focus on language represented a cultural need to be heard but also understood as a distinct culture separate from other francophone nations.

As part of their demands, the FLQ wanted their manifesto read live on the national broadcasters CBC/SRC in its entirety. After days of negotiations, the government agreed.

The manifesto sent shockwaves through the province. For the first time in many Quebecois’ lives, they recognized themselves in the language on TV and radio. The manifesto, written in joual (a colloquial French associated with the Quebec working classes), described unequal working conditions and systematic abuses against the province’s French majority at the hands of big business and the English elites. The speech resonated deeply, forever changing the landscape of Quebec politics and culture.

Language became the central agent of change, more so than any of the violence perpetrated during this period. In all its complexity, language became the central focus of the journalists and documentarians seeking to capture this lightning moment in Quebec history.

The FLQ was founded in 1963 as a response to a decades-long democratic struggle to improve French Canadians’ rights with little success. Its founders saw violence as an effective agent of change. Their goal? For a socialist insurrection against their oppressors, the overthrow of the provincial government, Quebec’s independence from Canada and the establishment of a French-speaking “workers’ society.”

Symbols of Federal “colonial” institutions became the easy targets of the FLQ’s first wave of attacks. From March to late May 1963, the FLQ carried out five violent assaults, mostly using bombs. Their targets included RCMP offices, railways, McGill University, and most infamously, mail bombs planted randomly over Westmount, a wealthy English neighbourhood. A 65-year-old man, William Vincent O’Neill, was killed when a bomb detonated at the Canadian Army Recruiting Centre. Walter Leja, a bomb defuser, was gravely injured in the Westmount attacks and spent most of his life in hospitals, where he died in 1992.

On June 1, 1963, eight leaders of the FLQ were arrested in a surprise raid. More arrests took place over the month. Undeterred, the movement continued. New cells emerged, and even as some key members of the FLQ were imprisoned, attacks and robberies continued over the next few years.

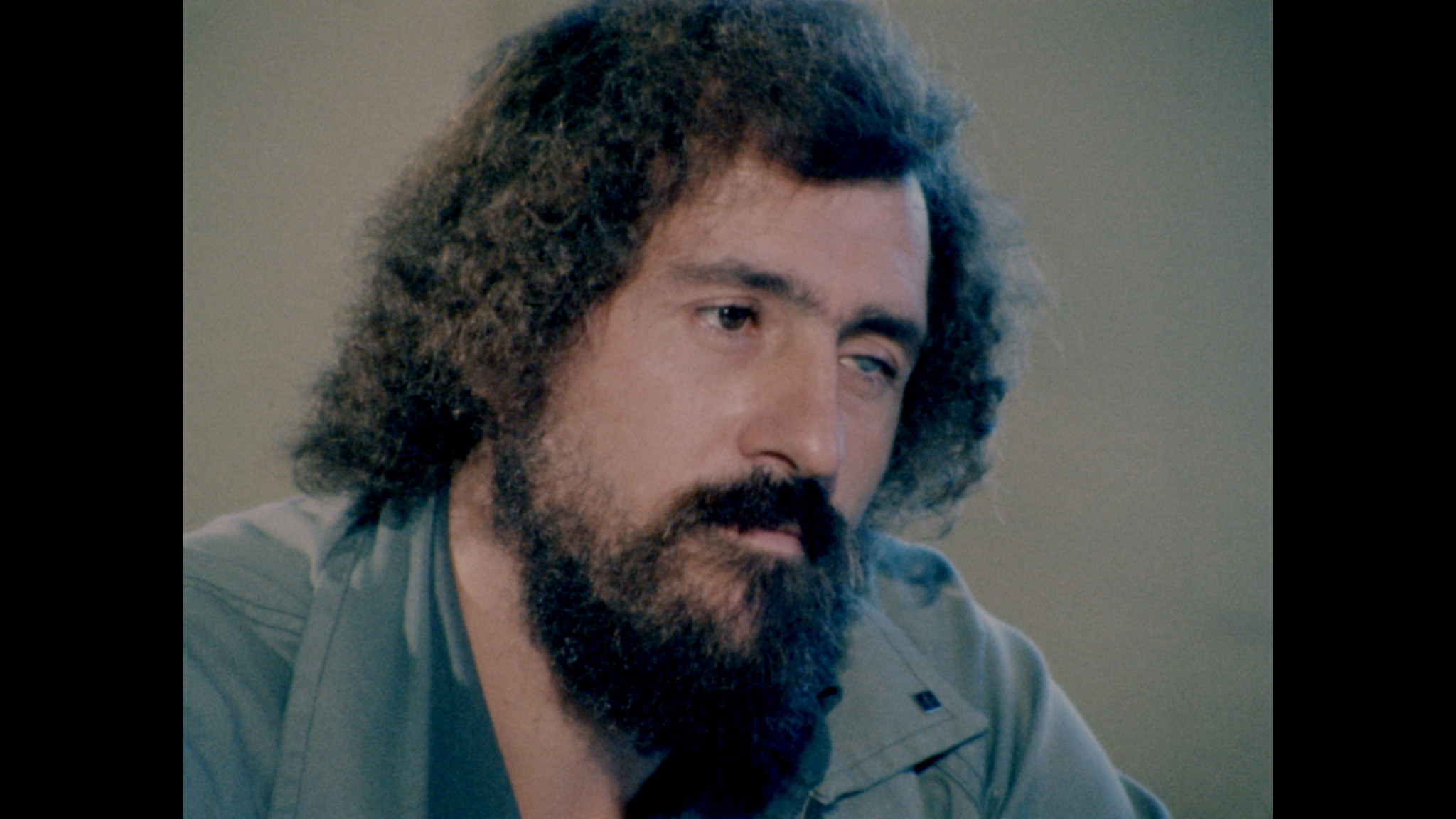

In 1967, the first film devoted entirely to the FLQ was released, appropriately called, FLQ. Director Jean-Pierre Masse interviewed four members of the FLQ; François Gagnon, Jacques Giroux, Jean-Denis Lamoureux and Raymond Villeneuve. They were young and gregarious as they discussed and debated the foundations of their movement. The documentary serves as a unique document of their radicalization as the young men spoke candidly about their ideas and experiences. Masse’s first question was straightforward, “Why did you choose violence?” We have shots of the men looking at each other around the room, smiling and uncertain. Then, Denis Lamoureux answers, “I didn’t choose violence in 1963.” As the shot changes, and the group now sits outside, he continues his thought. His actions were not violent; they were “counterviolence.”

The young men, mostly from working-class backgrounds, discuss their growing frustrations in Sixties Quebec. It became clear to them that the democratic struggle was not working, and concurrently, the dream of an independent Quebec could become a reality. But, if they wanted it to happen in the next 100 years, they needed to take radical measures.

For the first time on film, critical members of the FLQ discussed from their POV their involvement and actions in the first wave of attacks. As such, it is meaningful and retains archival value. In this case, language meant having the opportunity to have your voice heard.

Taire Des Hommes (1968) from Alexandre Piral on Vimeo.

One year later, another film about the FLQ would be released, this time by the NFB. Taire des hommes directed by Pascal Gélinas and Pierre Harel documents the events of June 24, 1968, during a parade on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, one of Quebec’s major celebrations. At that parade, members of the FLQ attempted an attack on a gallery where Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who was recently elected as head of the Federal Liberal party and would be elected as prime minister of Canada literally a day later, was seated. Chaos quickly emerged, and the documentary focuses on the violence that follows.

Just the title of Taire des hommes insinuates a focus on language. It’s a double-entendre that plays on the similarities between the words “earth” (Terre) and “behave” (Taire). It’s also a comment on the still-unfolding Expo 67 and the world’s fair theme, Terre des hommes, a utopian reflection on man’s innovation and relationship with the world around him.

While we see footage on the street, mostly disproportionate and often random examples of police brutality, the film is mainly composed of various testimonies of passers-by caught in the fray. The diversity of voices is quickly apparent. The different social classes emerge in their different tonalities and choice of words. Often, the film cuts from one voice to another, highlighting the diversity in linguistic expression and capturing the shared unease over the police’s brutality. Rather than focusing in on the FLQ attack, the discussion centres on the law and the government’s action.

By October 1970, the FLQ had gained new momentum. On October 5, 1970, two members of the “Liberation Cell” of the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross. Shortly after that, they released a list of demands, including the exchange of Cross for “political prisoners,” safe passage to Cuba and the CBC/SRC broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto. The government began negotiations and agreed to broadcast the FLQ manifesto in full on October 8. On October 10, members of the Chenier Cell abducted the Deputy Premier of Quebec, Pierre Laporte. Tensions escalated, and Trudeau imposed the War Measures Act on October 16, which meant the suspension of habeas corpus, giving wide-reaching powers of arrest to police. One day later, the FLQ announced the execution of Laporte. His body was found shortly after that. As police continued the search for Cross, the FLQ confirmed that he hadn’t been executed. Cross was released alive on December 4, 1970.

Action: The October Crisis of 1970, Robin Spry, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The full events of October are portrayed in an NFB documentary by Robin Spry, released simultaneously in English and French in 1973. Action: The October Crisis of 1970 does more than offer an overview of events jumping from one chapter to the next. Spry features extended political speeches and long testimonies. In both English and French versions of the documentary, there was a similarly dispassionate narration. Language comes to the forefront in various ways, in how the film is structured and how the events themselves unfolded.

The first long passage occurs as Spry’s camera records a TV broadcast of an announcer reading the FLQ manifesto. Seen in full, as it would have been for people across Canada, we are allowed a greater understanding of its impact. The specific linguistic nuances, which veer from poetic to crude, reflect a common language rarely seen on TV at this time. However, the original English translation does little justice to the specific violence of some terminology, especially regarding particular politicians, and also failed to capture how slang and English lingo is employed.

Broadcast before the murder of Laporte, the FLQ manifesto garnered sympathy from the average Quebecois. Their descriptions of oppression by the English and the French majority’s lack of opportunity, resonated with the majority population. Even as support for the FLQ died out, the manifesto reading became a huge turning point for the separatist movement in Quebec.

While the first half of the film is primarily devoted to an escalation of events, Spry’s documentary slows down towards the middle section. Spry shifts focus from recounting events to showcasing extended testimonies of politicians. Rather than reduce their speeches to snappy catch-lines, he gives room to their full addresses. While all around they condemn violence, some are more sympathetic than others to French Canadians’ oppression, demonstrating a growing divide across the country. Even in the title, “Action,” we understand that the politicians are speaking rather than acting. Aside from NDP stalwart Tommy Douglas, no one interviewed in Ottawa opposed the controversial implementation of the War Measures Act by Trudeau. The growing frustrations of the FLQ over the glacial pace of progress grew increasingly apparent.

Small nuances emerge through this approach, such as the news media’s calls for politicians like Trudeau or Levesque to “repeat” in English their speeches. Since they spoke with ease in both languages, Trudeau and Levesque became mirror images in this context. They were politicians who come to very different conclusions about Quebec’s future. Both men were also, integrally, viewed as passive and inactive by the FLQ.

Reaction: A Portrait of a Society in Crisis, Robin Spry, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Spry would follow up Action with a lesser-seen film, also for the Board, called Reaction: A Portrait of a Society in Crisis, released the same year. It is composed of a series of interviews with different anglophone communities in Quebec and their reactions to the FLQ crisis that was unfolding. The film opens with an explanation that the documentary reflects a specific moment in time. That, three years later, in 1973, when the film was released, the emotions had likely dulled, and the ideas expressed shifted. As a result, Spry decided to redact all names.

The film offers various viewpoints, from those who outright condemn the separatists’ movement to others more sympathetic to their cause. Many participants comment on never having given real thought to the idea of popular support for an independent Quebec before the events of October 1970. It’s a film that forces its participants, all assembled in different groups and contexts, to debate their feelings about what were then current events and possible futures. The language itself becomes an essential point of debate. Some members are frustrated at the idea that they might be “forced” to use French. Others, in particular a group of Hungarian immigrants, see it as an inevitability, if not a necessity.

In 1972, Joyce Wieland, an experimental Canadian filmmaker, made a short documentary on one of the FLQ’s most important members, Pierre Vallières (who also lends his name to her film). Considered one of the most critical voices of the movement, he wrote the still controversial Nègres blancs d’Amérique (1968). He would continue to support radicalism, including violence, throughout his life, as a means for political change.

Wieland’s film strips away nearly all context and rarely veers from a close-up of Pierre Vallières’s mouth as he reads out his ideas. The only shifts in focus happen in 16mm film reel changes, where the shot is reframed, Wieland occasionally speaks, and a shot of a wintry landscape can be seen. The film is controversial mainly due to Vallières’s rhetoric, as he equates the struggle of French Canadians with that of black people in America. He makes similar sweeping and reductive statements about the Indigenous peoples of Canada. His use of language is inflammatory and radical. Jonas Mekas, writing about the film for the Village Voice, stated:

“I was helped, when looking at the film, by Joyce’s concentration on the words, on the voice. She eliminated all visual distraction, including the speaker’s face. It’s the voice, the tone of the voice, and the meaning of what is said that comes through. The sincerity and truth of the voice comes through. Ms. Wieland displays in this film the maximum respect for what’s being said in it. The purity of her approach, her formal choice, only increases the sharpness of the truth presented in the film. “I look at this film also as a critique of most of the so-called political documentaries. … Joyce Wieland concentrates on the speaker’s voice, she presents Pierre Valliere’s’ [sic] voice in close-up, so that nothing is hidden. And the truth of the voice, the sound of the voice, the nuances of the voice, its vibrations, its colors merge so totally with what is being said that no other images are needed to make the point.”

Mekas’s analysis, though, downplays a certain level of the grotesque involved. The close-up, shot in muddy colour, is not a flattering one. The camera’s intimacy feels invasive and aggressive.

La liberté en colère, Jean-Daniel Lafond, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Decades later, in 1994, a much older Pierre Vallières returned in the documentary La liberté en colère, directed for the ONF/NFB by Jean-Daniel Lafond (latterly the husband of Canada’s Governor General Michaëlle Jean). In this film, he was joined by Charles Gagnon, Robert Comeau and Francis Simard. The film is divided up between a university presentation, a cabin trip and other speaking events. Intended as a reflection on the events of the 1960s and 1970s, the film also touches on the new struggle for independence and the ways in which time impacts on ideas and perspective. While remaining controversial figures, the former featured members of the FLQ, have been mostly accepted by the larger Quebec society.

Much of the film focuses on the tensions between Pierre Vallières, who stands firm in his radical beliefs (though he did renounce violence), and former FLQ member Charles Gagnon, who has largely abandoned them. While Gagnon saw, by 1994, the Parti Quebecois’s (PQ) popularity as a victory, Vallières saw the PQ’s allegiance with the status quo, in particular capitalist and patriarchal values, as inherently doomed. Tension is high throughout Lafond’s doc, especially when Vallières expresses frustration that Gagnon can’t distinguish their friendship from their differing rhetoric.

More than films released in the ‘60s and ‘70s, La liberté en colère shows that there are deep divisions concerning how the FLQ succeeded in shifting social ideals while failing to initiate the intended radical leftist changes. There’s a lot of focus on the concept of utopia, which Vallières continually invokes. Vallières seems out of step not only by his radicalism but also for his twisted optimism. Society, for one reason or another, seems gripped with disillusionment rather than hope, content but rather uninspired by the idea of sweeping political change.

With the most recent 50th anniversary of the October Crisis, we see another wave of documentaries about it. Félix Rose made a documentary, Les Roses, trying to make sense of his father and uncle’s direct involvement with the kidnapping and murder of Laporte. For the CBC, Geoff Turner hosted a podcast called Recall: How to Start a Revolution, which is as much about memory and time as it is on the specifics of October 1970. Both documentaries are reflections on a past that might not be so distant, but feel emotionally out of reach, with so many unique details and circumstances lost as the story is told and retold across the ages.

As the October Crisis stands as such a heavily documented event, the shifting perspectives on how it is felt and experienced today reflect in the shifting points of view of documentarians who have chosen to revisit the events. The original films made during the period illuminate in stark detail the tensions and moments that might otherwise be lost to history, while more recent films reflect on how revolutionary ideas fade and the details that stand the test of time paint an incomplete portrait of actual events.