People have a way of celebrating those who are the first to reach the top of the mountain without necessarily acknowledging the struggle they endured along the way. For Black pioneers in documentary filmmaking, their ascent often meant climbing solo with little support. POV reached out to award-winning filmmakers Selwyn Jacob, Sam Pollard, and Sylvia D. Hamilton to learn about some of the adversities that they had to overcome when embarking on their filmmaking journeys.

Working in film had long been a dream of Canadian filmmaker and producer Selwyn Jacob when he was a young boy growing up in Trinidad. Little did he know that all it would take was a magazine cover, featuring a Black man who had gone to the University of Southern California (USC) film school, to make his once cloudy path to filmmaking become clearer.

Travelling to Alberta to get his undergraduate degree in education, Jacob eventually went to USC in the mid-’70s, where he was one of two Black students in the film program. “I was 50% of the program” Jacob remembers, “so in terms of mentorship, there wasn’t anything.” He had to forge through the unfamiliar terrain on his own, making contacts any way he could. Jacob chased after guest speakers, like pioneer African-American actor Roscoe Lee Browne, in hopes of getting their contact information and conversing with them. Thanks to a Black woman who worked at the school’s film library, Jacob found another networking avenue, which allowed him to meet legendary filmmaker Robert Wise, who agreed to let him visit the set of the film he was making at the time.

Despite the connections made, Black Canadian filmmakers were not able to drink from the fountain of opportunities like their white counterparts. “There was no such thing as a film industry,” Jacob says when reflecting on moving back to Alberta after graduating from USC. While commercials and the odd feature film were being made in Canada, the few jobs available were not going to those who looked like him. Even though he was fortunate enough to be taken under the wings of Fil Fraser, the ground-breaking Black Canadian broadcaster and producer, who was producing a film with Jacob’s drama teacher, Jacob had to rely on his teaching degree to survive. However, even that presented a different set of hurdles he had to jump over.

“You could not really get a job teaching in Edmonton,” Jacob notes. As if exiled into a foreign land, individuals of Caribbean descent and other visible minorities were frequently assigned to teach in the countryside. “I felt I was being punished and pushed out to the boondocks,” Jacob recalls of his time teaching in a community 100 miles north of Edmonton. As fortune would have it, he was able to turn the lump of coal he had been given into a diamond. While there, he learned about a nearby community comprised of descendants of African American settlers that came to Canada in 1901. Their story became the basis of his first documentary, We Remember Amber Valley (1984).

Using various Canadian cultural grants to fund his early films, Jacob found himself wearing many hats on the productions. “I literally had no options. I couldn’t say I was waiting for a Black editor … I was the Black content in the production,” says Jacob.

It was only when Jacob attended the 1988 Toronto International Film Festival, then called the Festival of Festivals, with his film, with his film The Saint from North Battleford, that he felt the warmth of a community who shared his dream and passion for telling Black stories in Canada. Introduced to the Black Film and Video Network by Cameron Bailey, then TIFF programmer and now TIFF artistic director and co-head, he felt at home amongst the Black filmmakers, producers, critics, photographers, publicists, and actors who were determined to bring diversity to the Canadian artistic landscape. “I became a sort of long-distance member,” Jacob recalls. “I’d say I wish I had somebody, another Black person, to work with me.”

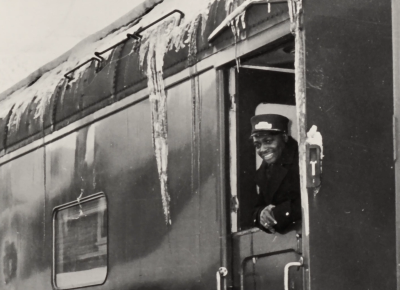

Jacob’s wish was eventually granted as his prolific career saw him working alongside creative minds of colour as both a director of documentaries like The Road Taken (1996), his beautiful and powerful portrait of Black sleeping-car porters who maintained their dignity in the face of racism when working on Canada’s railways, and as a producer for the National Film Board (NFB). Producing a wide range of documentaries that includes Obâchan’s Garden (2003), Mighty Jerome (2010), Crazywater (2013), Ninth Floor (2015), Because We are Girls (2019), and Now Is the Time (2019), Jacob has created space for Black, Asian, and Indigenous stories often neglected in Canadian film. Even now, a year and a half into his retirement from the NFB, he is still providing mentorship to the next generation.

The Road Taken, Selwyn Jacob, National Film Board of Canada

Having mentors of colour was greatly beneficial in shaping the career of filmmaker, editor, educator, and producer Sam Pollard. “Mentors are invaluable, that’s why I am a teacher,” Pollard says. While he was fortunate to work under the tutelage of Victor Kanefsy, who taught him the craft of editing documentaries, it was African-American filmmakers like George Bowers, St. Clair Bourne, and Henry Hampton who impacted how Pollard approached the medium of film.

Reflecting on the early years of his career, Pollard notes that “the biggest challenge I faced was to come to what I call a revelation that my Blackness shouldn’t be submerged in this notion that we should become a part of the American melting pot.”

Working with Bowers taught him not only a level of professionalism and discipline, but also that it was possible to be a working Black editor for feature films. Bowers was also instrumental in introducing Pollard to Bourne, a meeting that he considers a “personal milestone” in his career. Pollard cites his relationship with Bourne, which was formed when they spent six months in the editing room together working on Bourne’s film Chicago Blues (1986), as a key turning point for him. During their time together they discussed not only the film, but also the responsibility that they held as filmmakers of colour.

Pollard walked away from that experience a changed man. “I don’t have to say, ‘don’t call me a Black editor, just call me an editor,’” Pollard explained. “I was able to identify as an African-American editor and then, later on, as an African-American producer and director who could do any kind of film.” This affirmation of self was further fostered when he began working with Hampton on Eyes on the Prize 2 (1990). Shaping him as a director, Hampton showed Pollard another perspective on how to use documentaries to tell compelling stories.

One just needs to look at Pollard’s own career to see that the seeds planted by those who taught him have produced a bouquet of delicious fruit. Whether it is his editing work on the acclaimed Spike Lee documentaries 4 Little Girls (1997) and When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) or crafting his own nuanced explorations of the African American experience as a director, Pollard is always challenging his audience to consider perspectives different from their own. He gives just as much weight to films such as Mr. Soul! (2018) and Black Art: In the Absence of Light (2021), which both focus on the vital contributions Black artists have made to the art world and society, as he does to films like Slavery by Another Name (2012) and The Talk: Race in America (2017), which examine the relationship between race and policing in America.

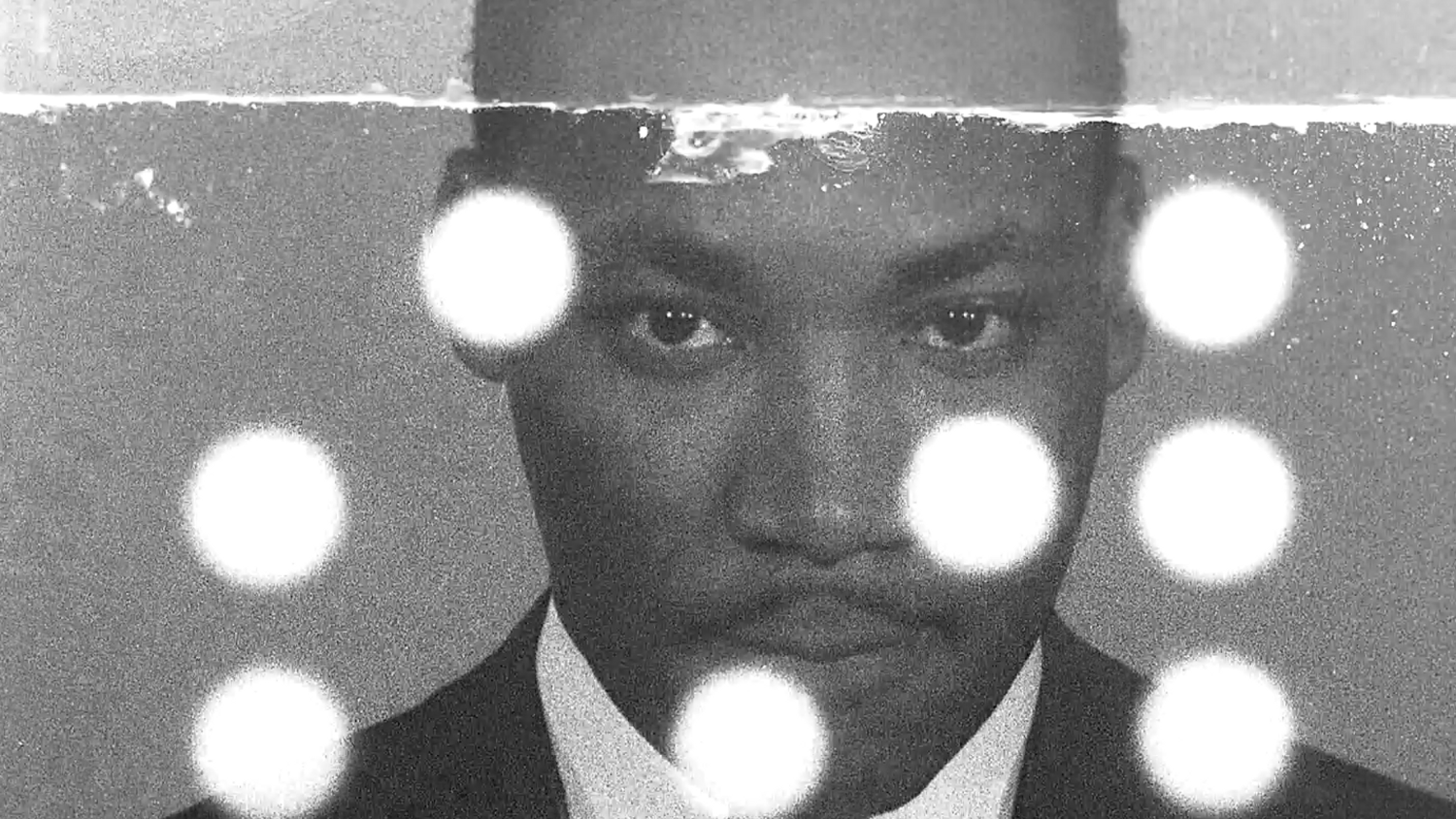

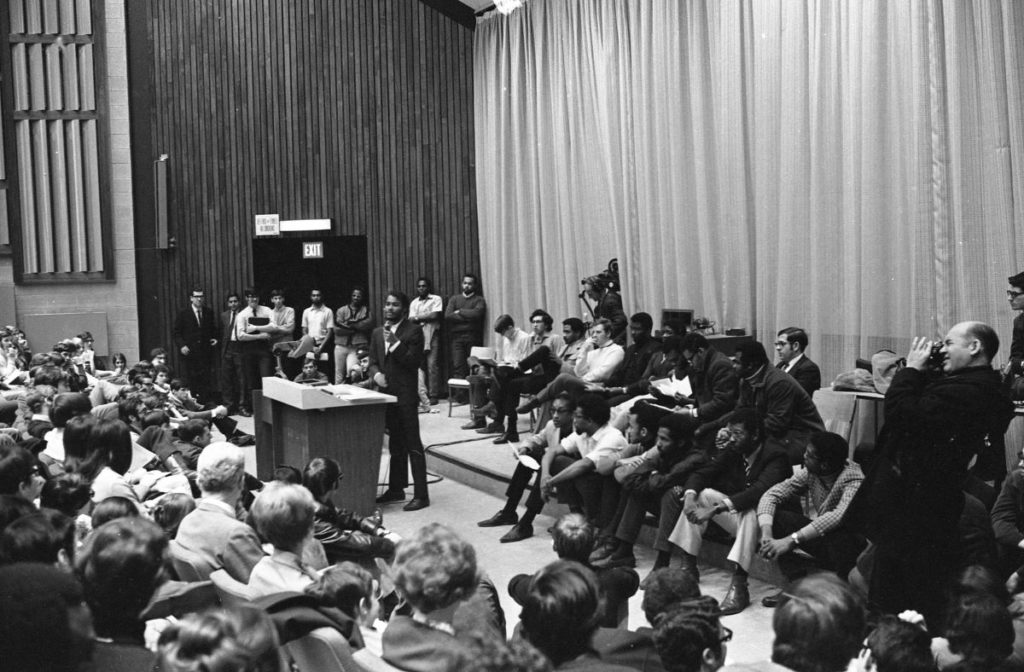

Showing that there are many dimensions to the Black experience, Pollard’s films always paint complex and thought-provoking portraits of his subjects, regardless of whether they are average Americans or renowned individuals. As he acknowledges, there are always additional obstacles when approaching stories about beloved figures. When it came to making MLK/FBI (2020), Pollard notes that “the challenge we had as a filmmaking team, myself and Ben Hedin, was: how do we tell this in a different way?” What they realized was that the role J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI played, using unethical and ruthless surveillance tactics to silence the famed activist and preacher, had largely been ignored in the revisionist history of Dr. King told today.

Although Pollard understands the importance of holding up a mirror to a nation’s sins, he knows not everyone is willing to see their own reflection staring back. As many filmmakers can attest, even getting the money to build the mirror can be a struggle. “Funding is hard no matter what colour the filmmaker is or what the film is about,” says Pollard. “It is doubly hard for Black filmmakers.” While MLK/FBI gathered funding in a year and a half, quicker than his previous works, it was still a challenge.

Securing the financing can often feel like a Rubix cube where all the necessary colours refuse to align. As Nova Scotian filmmaker, producer, journalist, educator, and poet Sylvia D. Hamilton notes, it is one of the primary hurdles that comes with making films. She recalls the struggle that Black Canadian filmmakers experienced in the ’80s and ’90s when it came to acquiring funding from film agencies and broadcasters. “We were not part of ‘the club’ and had to press, argue, shout, do whatever it took to at least get in the door,” says Hamilton. Unfortunately, getting in the door did not guarantee a seat at the table. As many found out, there was often only room for one Black story on a given slate. Hamilton recalls that they were routinely told, “Well, we funded a film like that … last year, or the year before.”

Citing the recent creation of the Black Screen Office, headed by Joan Jenkinson, as a step in the right direction, Hamilton also makes it clear that funding is only one aspect of concern. Noting the dearth of education on the films by Black filmmakers in Canada, she points out that equal attention should be paid to the filmmaker’s creative process. “Talk about the work from a craft-aesthetic perspective; how the work is made, what the artistic decisions the filmmaker struggled with are,” Hamilton says.

As a filmmaker who has continually helped to usher in new voices, she co-created the New Initiatives in Film program with the NFB to aid women of colour and First Nations female filmmakers, Hamilton knows the value of unpacking and fostering artistic visions. When reflecting on the individuals that influenced her in the early stages of her career, she also cites the likes of Fil Fraser and St. Claire Bourne as instrumental figures.

“Fil’s example showed me it was possible to work in the film production field,” Hamilton states when recalling their meeting at a conference for Black Artists. When she was pitching Portia White: Think of Me (2000), her acclaimed documentary on the cultural impact of White, the pioneering Black Canadian concert singer, it was Fraser, then President and CEO of Vision TV, who supported the project. The pair would eventually get the chance to work together when Hamilton directed an episode of the television series Hymn to Freedom.

If Fraser provided the proof that a career in film production was possible, then Bourne served as a reminder of the responsibility filmmakers have in telling diverse stories. “Everyone should have the right and opportunity to see themselves reflected in the cultural expressions of the land in which they live,” she recalls hearing Bourne say while attending a workshop for Black Canadian filmmakers.

The recipient of the 2019 Governor General’s History Award, Hamilton’s documentaries have provided a crucial voice for the Black experience in Canada. Whether celebrating the oral history and traditions passed down between Black women in Nova Scotia in Black Mother Black Daughter (1989), which she co-directed with Claire Prieto, or exploring systemic racism in the realm of education in Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia (1992) and The Little Black Schoolhouse (2007), her films expose the longstanding cracks within Canada’s mask of multicultural harmony.

While there is a certain level of trauma one must wade through when revealing systemic racism, these three filmmakers skillfully offer a sense of hope in their works. “I’m interested in finding ways to visualize all that we are, or as much of what we are as can be placed in the time limited frame,” Hamilton says. Understanding the multi-faceted layers of Black life, Hamilton is careful to not betray the trust her subjects have placed in her by exploiting their struggles. Pollard notes that his optimistic outlook is part of his personality. Despite being cynical about certain things related to the treatment of people of colour around the world, he acknowledges that “somehow we are able to keep going and keep fighting.”

Black Mother Black Daughter, Sylvia Hamilton & Claire Prieto, NFB

Part of this fight includes ensuring documentarians have the tools needed to tell all types of compelling stories. When asked about what piece of advice they would give to the upcoming filmmakers and producers, Hamilton raised the importance of self-care and removing negative individuals from one’s inner circle who “can drain your precious energy and creativity.” Noting that not all feedback is meant to tear you down, Jacob admits to struggling with constructive criticism early on as a filmmaker. “You have to develop a thick skin,” he states. “You may not agree with them, and you may not make that change, but show some appreciation because it takes a lot on somebody’s part to sit down and and say, ‘I am going to write you a note.’” Pollard also stresses the need of having a tough resolve to survive the ups and downs of the industry. “People are going to say you are not good enough,” he says. “You are going to have moments of self-doubt. But you’ve got to be tenacious. Even when you stumble you have to pick yourself up and move to the next project.”

While it is important to prepare the next generation to carry the torch that filmmakers like Hamilton, Jacob, and Pollard have lit, the film industry needs to do its part as well. Despite the promises of drastic changes during this racial reckoning, these declarations have been met with a cautious optimism. “We experienced a period in the ’80s (and even before that in the ’70s) when we heard much talk about equity, diversity, and institutional racism,” says Hamilton. She notes that statements without continuous accountability are nothing more than hollow words.

Pollard shares similar sentiments, recalling a ’90s front-page article in the New York Times Magazine saluting the new wave of Black filmmakers and Black stories. Unfortunately, that Black wave subsided quickly as the gatekeepers within the industry continued to surf in predominately white waters. Stressing the need to always be mindful of the sudden declaration to do better, Pollard states, “The question you always have to ask yourself is, how long will that last?”