“When it’s done intentionally to look real, it’s almost impossible to detect,” says Another Body director Reuben Hamlyn. The filmmaker, speaking via zoom with fellow Another Body director Sophie Compton, explains the deepfake process that’s both at the centre of their film and a mode for its delivery. The documentary tells the story of two young women, “Taylor” and “Julia,” who discovered horrifying pornographic videos with their faces inserted on the bodies of other women. The videos are products of the artificial intelligence (AI) practice known as deepfake in which users can manipulate images to alter identities. The rapidly developing technology outpaces the laws that govern it. Another Body tracks the women’s stories, notably Taylor’s, as they investigate who is behind the deepfakes.

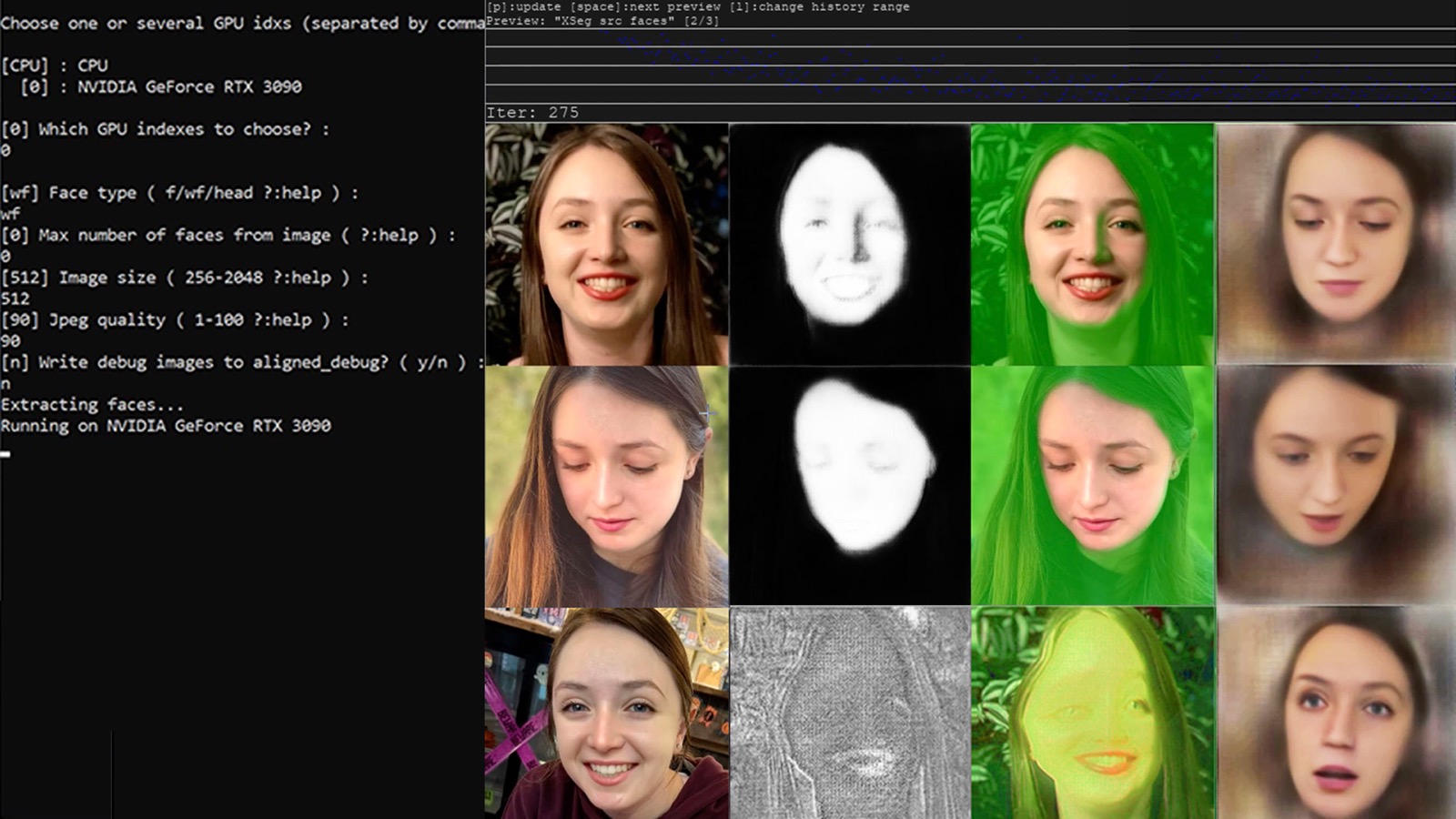

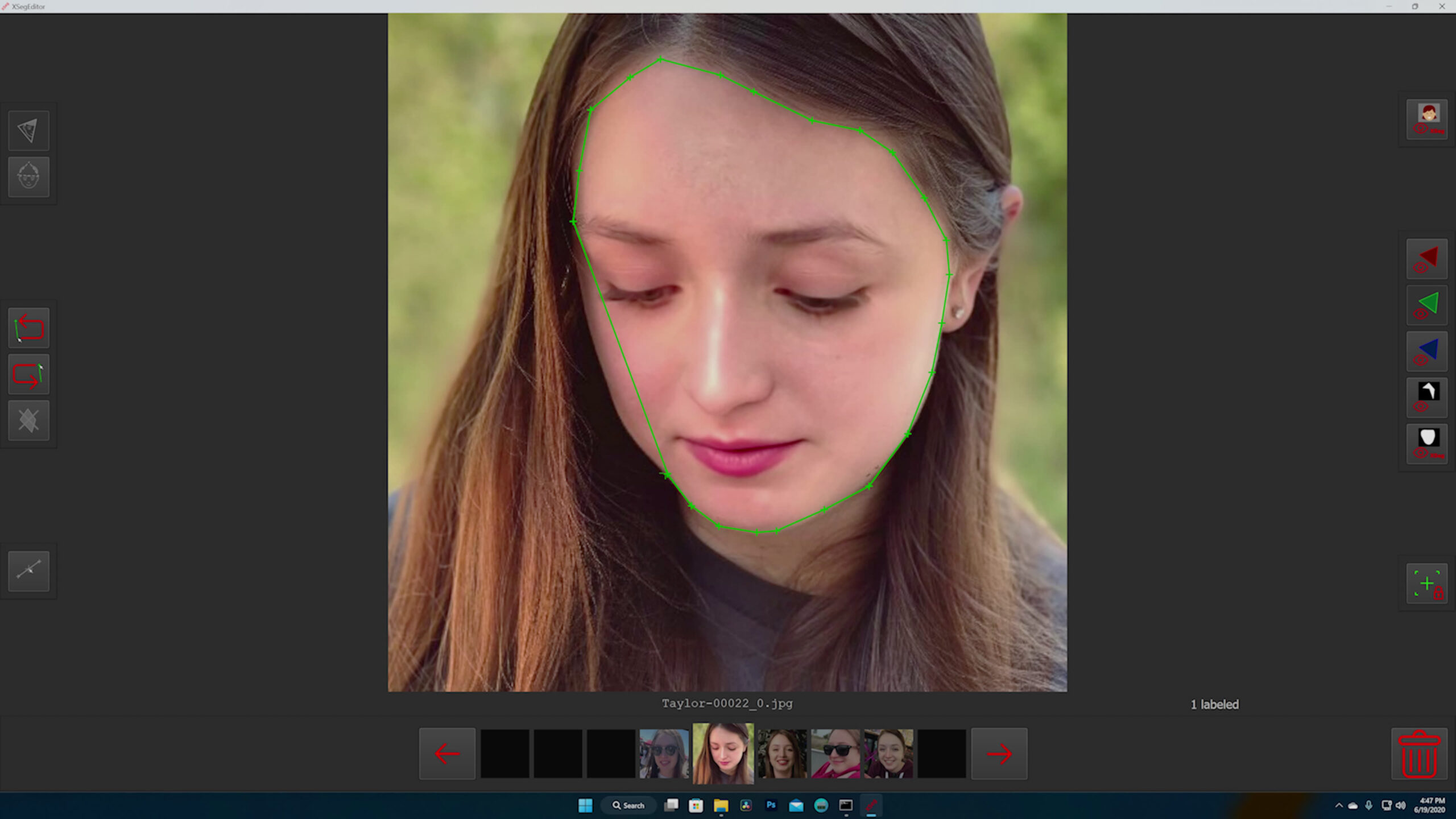

Another Body further demonstrates the sophistication of artificial intelligence by masking Taylor and Julia. Just as their names are pseudonyms, their faces are deepfake disguises. Another Body reveals its construction to viewers partway through, however, illustrating the role that context plays in the ways in which images are made and received. It surprises through the uncanny manipulation of images to compel viewers to understand how deep the rabbit hole goes.

The investigation leads Taylor and Julia to a former schoolmate, “Mike,” with an extensive portfolio of deepfakes, including YouTuber and influencer Gibi AMSR, who uses her platform to amplify the voices of women expected to remain silent. For Compton and Hamlyn, these stories are just the beginning of a pervasive web of predatory violence. The filmmakers harness the power of documentary to take their efforts raising awareness for image abuse through the #MyImageMyChoice campaign to a wider audience. It’s a timely conversation starter with the ethical boundaries of AI recently proving a sticking point in the actors’ strikes and the President Biden signing an executive order to curve the limits of the developing technology. As far as true crime goes though, Another Body tells just one of many cases.

POV spoke with Hamlyn and Compton by Zoom ahead of the theatrical release of Another Body.

POV: Pat Mullen

SC: Sophie Compton

RH: Reuben Hamlyn

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I understand that you found Taylor while performing online research, but how did outreach work knowing that she’d had a traumatic experience online?

SC: We reached out a month after she’d been deepfaked. We spent a lot of time thinking about how to reach out, made sure that we were giving resources and support, and ideas for lawyers, as well as being transparent that we were making a film, but not trying to push that on her. It’s a testament to her character that she was curious and interested and willing to speak. She’d noticed that I’d clicked on her LinkedIn and thought, “Who’s this British filmmaker looking at my LinkedIn? That’s so weird.” This was a moment when she was getting a flood of messages from random people.

We did reach out to other people, some of whom we ended up being in touch with, but a lot of people didn’t reply for completely understandable reasons. Taylor was one in a million. So much of this [film] is about deep trust and instinct. As soon as we spoke, we felt an affinity for each other that enabled her to sign onto the project essentially after one call, which is unbelievable given the onslaught of other people who have been contacting her negatively.

POV: I wonder if the LinkedIn trail helped because she could see who you are?

SC: We made sure to be really clear about who we were. I put a link to my personal social media and to our activism work—we’d already started building our campaign at that point. The fact that we’ve been activists and in the trenches with her making the film has been so essential while handling such sensitive subject matter. It felt like a proposition that wasn’t extractive.

POV: How much of the story did you know before getting into production? Were you aware of the extent of Mike’s activity?

RH: We were aware of very little at the start. As Sophie mentioned, when we got in contact with Taylor, the videos had been uploaded a month before. I think Taylor had discovered them two weeks before. We’d also seen the deepfakes of Julia, got in contact with her, and saw that she went to the same university as Taylor. We made the assumption that they were from the same target, but we didn’t put them in contact. We didn’t know if they were friends; we just interviewed both of them. When they naturally discovered each other’s stories, they came together. All those twists and turns were totally unknown to us at the beginning, and we were rolling the dice.

We are very lucky to be able to follow this story, although it’s disappointing that Taylor didn’t find the resolution that she was seeking. But it’s inspiring to see her growth and, ultimately, we believe it was a cathartic process for her to reflect on her experiences and excise the negative emotion through the process of sharing her story.

POV: How much are stories like those of Taylor and Julia consistent with other stories you’ve encountered through your activist work? Do people find resolution in other stories?

SC: The sad reality is that they got so much further than almost anyone else that we’ve spoken to. The vast majority of people do not identify their perpetrator, and therefore there is no legal justice and there is no resolution personally or privately. It’s only because Mike did this on such a huge scale that we were able to triangulate it. He left so many breadcrumbs. In that sense, it’s unique.

This abuse aims to shame, silence, and minimise people’s lives. It has that effect profoundly. I do wonder what would’ve happened if we hadn’t have been there, if Taylor hadn’t discovered Julia, and then reached out to Gibi. In Taylor and Julia’s case, they managed to transform this horrendous thing into something empowering: going to the White House, speaking to Gibi, the way that Gibi then was able to put her message out publicly and there was this flood of support—that never happens. Gibi was the first person in the ASMR community to speak out about this. There are very, very few actors and actresses talking about this publicly.

RH: In a scene that was cut from the film when we were streamlining the edit, Taylor does get a detective assigned to her case. That never happens. The only reason why that happened is because her dad had a friend who had a cousin who was at the state police. Using that connection, they put some pressure on and she was assigned a detective. Without that connection, that would never have happened. Even that was very insufficient with the way she was dealt with by them. It really shows quite how dire the situation is for most people.

POV: How do you work with participants like Taylor and Julia to share their stories without re-traumatizing them?

SC: Re-traumatization is different from being triggered. We can be afraid of things that might trigger us, but sometimes that can be part of a healing process. When we went into the investigation session, we thought carefully about how to support Taylor before and after. We made sure we were there on the call throughout if anything was needed, and we made sure that she had the support that she needed emotionally and psychologically in terms of therapy and that it wasn’t connected to us, the production team. We didn’t want it to feel like it was dependent on her delivering. We were all confident that, although it was going to be painful, she wanted to find out the truth.

You’ve just got to keep remembering the human costs and the reality, but also where this sits in the broader goals. If it’s just for the film, then that’s one thing, but if it’s also for her closure and for her own investigation, then it becomes worth it. You have to work on your own internal process for when something feels like it strays too far. It’s a subtle judgment, but as a documentary filmmaker, you have to develop a strong access to your gut instinct. This process has made us feel the reality of the healing that happens when someone gains access to sharing their story.

RH: This film is built around trying to limit the risk of re-traumatization and make a cathartic experience for her. The decisions not to make a typical vérité film and for Taylor to self-record are partly tied to the themes of the movie, but it’s also given that she has issues with mental health and was in a vulnerable state. It felt good that she had agency over how and when her story was told. She’s the one turning the camera on and turning it off. But the amount of pornography and the way that we depicted the pornography in the film was a real question and it shifted.

It’s tricky because you don’t want it to be gratuitous. At the same time, you are fighting against people who don’t understand this form of pornography, and you need to show it in some way to convince them of it. In our research phase, we had conversations with Noelle Martin, who was the first person to speak out about being targeted by deepfakes. She implored us to not shy away from it and to show the horror of this community’s activity.

POV: You talked about trusting your gut and the role of a filmmaker, and there’s recently been a lot of attention paid to mental health practises for documentary filmmakers. How do you keep yourselves well while dealing with the responsibility of telling these stories and accessing all this material?

RH: The stark reality of it is that you don’t always. We were in a very supportive team and we could speak amongst each other, but there are times when you can’t afford to spend two hours in a communal therapy session. There are times when you have to drive forward to complete the film. There’s not enough money in documentary and deadlines are so tight. There’s rushes to get cuts complete, to meet festival deadlines. Documentary filmmakers take on a huge amount of responsibility for their subjects. It’s a very intimate and close relationship where trust is incredibly important and you are managing that. You are managing relationships with your whole team and as co-directors with each other, and then of course your own mental health.

It’s a lot to take on without prior training. There’s not a good guide for best practise and how to do this. You often have to navigate these difficult, ethical, and emotional quagmires while you’re in the production process and the editing process, and just doing the best that you can. Sometimes it’s hard to get everything right ethically as well. Sometimes we caught ourselves being like, “This isn’t right,” and we’d have to roll back and reorient. It’s difficult practise, but the outcome is so important. The amount of time we’ve spent on the phone together over the last four years has made it all possible.

SC: It’s important to build space because bad decisions are made in stress, panic, and fight-or-flight. I lived in the countryside during the making of this film, and that was essential. Making this kind of work forces you to do the internal work that we don’t do unless we’re carrying such responsibilities. You need to process your emotions and draw your own boundaries. Making documentaries, whilst it can be incredibly challenging, forces us to get our mental health life in order, in a way.

I think that the most challenging parts of this industry are often the ways that the industry itself and the financing models stand in the way of you doing your best work. The hard part is when you have to put down tools for a year, or two months, and leave survivors or contributors in a certain state. The mechanics of the industry are really obstructive to the cathartic and healing process of involved and the storytelling.

POV: One thing that I think is related to this topic is the care you take for Taylor. At what point did you decide that she would not appear as her real self?

RH: From the beginning we knew we would deepfake her. So few survivors had spoken out at that time because they’d become subject to a huge amount of abuse for speaking out. 4chan itself is known for the mob harassment, and we didn’t want to be responsible for putting our subjects in that line of fire. When we spoke to Taylor, we immediately offered it and she thought it was such an exciting thing to do: to reclaim the technology. She’s an engineer, she loves new technologies. It’s also a great demonstration of how powerful this technology could be for people who have only seen ridiculous deepfakes of Nicolas Cage’s face on Arnold Schwarzenegger’s body, which doesn’t look real.

POV: How did you approach the manner of integrating Mike’s story and that investigation into the film? There are no laws to protect Taylor or Julia, but Mike is protected by laws like libel and defamation.

SC: We felt like the chance of Mike bringing a libel case would be pretty slim. We’re confident that he’s the perpetrator and therefore he would be outing himself. Obviously, you go through the legal review and make sure that your information is watertight. Everything that we said in the film, we’d 100% stand behind in the court of law.

RH: Mike isn’t his real name, it’s a pseudonym as well, so I don’t think there’d be grounds for defamation nor libel because we didn’t use his real name.

SC: Gibi is currently pursuing a legal case against him based on this evidence. The lawyers believe that it’s extremely compelling evidence, so good luck to him if he tries to bring a defamation suit against us.

POV: How do you balance the role as activists and filmmakers?

SC: Having an impact campaign alongside the film creates a unique ecosystem where both sides enhance the other. The more work you do on the activist side, the more conversations you have where you’re building your audience, you’re building your research, you’re getting a much deeper sense of the issue. Plus, it’s the core of your marketing campaign. It’s the core of the champions for the film, and you work out each and every step along the way what can be done to solve this issue.

Now we’ve moved the conversation further to highlight how tech companies like Google, VISA, MasterCard, PayPal, and internet service providers are the infrastructure that allow these sites to continue and to be found and to be accessed. Biden released an executive order on AI on [October 30]. We thought it was going to have loads about deepfakes because we’d been involved in the White House’s report. They invited some of our survivors down and we were waiting with great excitement to see what this great announcement was going to be. It doesn’t actually seem like the material conditions have been particularly altered for survivors, so we’re back into fight mode. In terms of the industry and how documentarians work, we are not the experts—we are just the storytellers.

POV: Can you elaborate on some things you’re hoping to see addressed that weren’t in the White House’s order?

RH: Deepfakes needs to be criminalised. I’m against incarceration, but hardly anyone will actually go to jail because local police forces are so bad. But what I think it will create an ethical standard where consumers and creators will no longer be like, “Well, it’s legal. That means there’s nothing morally wrong with it.” People defer their ethics to whatever the laws of the land are. It will also make it harder for porn sites like Mr. DeepFakes to host this content and will interfere with it being a viable business model. It also will help us put pressure on companies like Google from directing people towards it, and we can then start going to internet service providers and being like, “Why are you hosting these websites? They’re hosting illegal content.” That’s a useful tool for us to target places that are driving people towards these videos.