If you’re in need of a creative collaborator, a co-conspirator to carry out an artistic endeavor, you might recruit a sibling to help realise your grand schemes. A younger brother to help stage a play in the backyard, or a twin sister to operate the camera for your next cinematic triumph. Although you might’ve battled for command of the remote control, you ultimately matured with the same films and television shows, alternating between channels, and developing each other’s cultural fluencies. Fights that erupted over the first slice of cake or the last drop of hot water in the shower were opportunities to practice conflict resolution, and in cases where immediate reconciliation was delayed, the dust always settled eventually, and life resumed as usual. For these reasons, many—from Joel and Ethan Coen to Lana and Lilly Wachowski—have naturally elected their sibling to Grey Gardens (dir. David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, and Muffie Meyer; 1975) serve as a partner-in-crime in the filmmaking process.

When one is asked to summon the mental image of a director, what generally appears is an idea of a lone genius with an uncompromising vision, the gaze fixed upon a detail in the distance, a single digit gesturing toward something that demands attention. A figure of authority, the director holds a great concentration of power to make creative decisions and transmit them across the orchestral ensemble of performers, technicians, operators, and other crew members in a unified manner. But with a pair of conductors, how does the dynamic shift and transform? What can the addition of a kindred voice offer—new insights, advice, brutal honesty? What do successful directing duos have in common and how are these partnerships formed in the first place?

For Josh and Benny Safdie, the New York-based filmmakers (and sometimes actors), the ascent to critical acclaim and prominence in the independent American film scene began with their father’s love of cinema. Growing up, the brothers were exposed to a wide range of films, which they were often shown to express what Alberto Safdie could not: Kramer vs. Kramer, for instance, was invoked amid a custody battle to draw a comparison between the events unfolding in real life and the film. Besides his movie consumption habits, their father also made extensive use of a camera to obsessively capture home videos of the brothers, not only documenting their childhood as an observer, but acting as a provocateur, devising moments of tension behind the lens to manufacture fights. Of the effect this camera had on their origins, Josh has said, “It’s kind of the birth of why we were filmmakers.” When Josh, the artistically inclined older brother by two years, eventually tried his hand at filmmaking during high school, he enlisted the help of Benny, whose disposition toward the sciences proved helpful when it came to editing with computer software. Thus began their creative partnership, one forged by an unusual upbringing and complementary skill sets: an alchemy of nurture and nature.

Whether in Daddy Longlegs (2009), their feature debut as a directing team, or Uncut Gems (2019), the star studded crime thriller, a sense of realism endures across their body of work as a result of their lo-fi guerilla filmmaking. Each scene feels spontaneous and fleeting, the precious outcome of employing handheld camerawork, non-professional actors, and real locations without filming permits. Even with the preparation and staging involved in fiction, it’s evident that the Safdies are in constant pursuit of life’s contingencies, those elusive moments revealing of our world that can easily slip through our fingers if we’re not careful to grasp them in time. In many ways, the brothers are in conversation with the language of direct cinema, a style of documentary that seeks to capture reality, allowing its triumphs and tragedies to unfold with minimal interference.

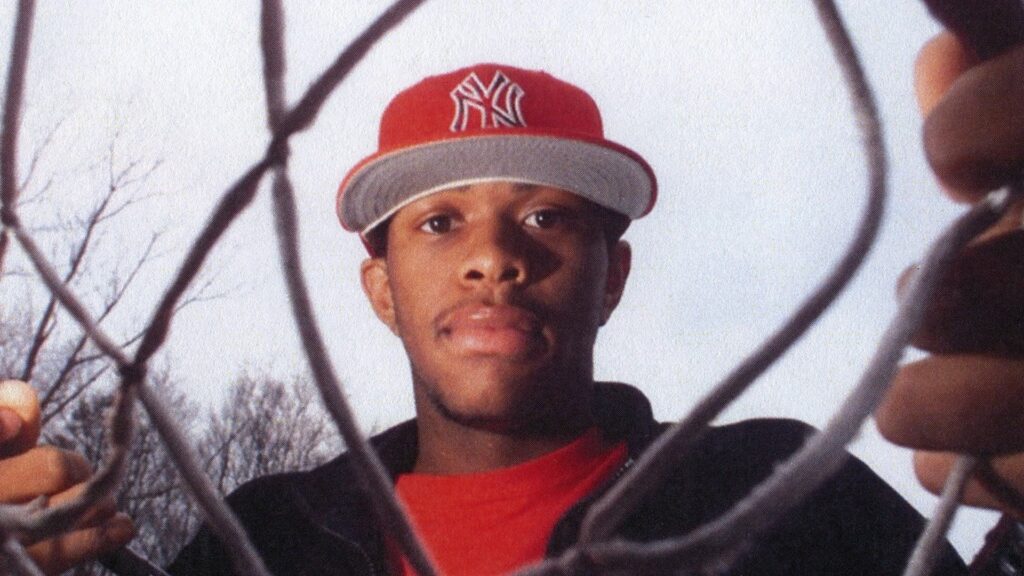

It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that Josh and Benny Safdie’s sophomore project as a team saw their first—and, for now, only—venture into documentary with Lenny Cooke (2013), which follows the titular high school basketball star leading up to the 2002 NBA draft. Weaving together observational footage, archival material, and interviews, the film is an intimate character study of a young prodigy vexed by misguided advice and a regrettable work ethic. Here, as in their other films, the Safdies are guided by their interest in examining class and wealth, laying bare the financial circumstances of their characters to probe their motivations and desires. An intimate portrait that combines their deep enthusiasm for film and basketball, the documentary displays the Safdies’ abilities to navigate nonfiction with the same sensibilities that have distinguished their narrative fiction efforts.

Often recognized as pioneers of direct cinema, Albert and David Maysles are another set of siblings who teamed up as directors. Five years apart in age, the brothers found their passion for filmmaking later in life after studying psychology during college. For Albert, who was conducting research and working in the field of psychiatry, the transition to film began when he travelled to the Soviet Union in 1955 to shoot a 16mm film titled Psychiatry in Russia, exploring mental healthcare and institutions as an extension of his work. Meanwhile, David’s entry into Hollywood arose through a fortuitous encounter: after being drafted into the army in the ’50s, he met a man whose uncle was Milton Greene, the still photographer for Marilyn Monroe. When he returned to the United States, he earned a job under Greene, serving as a production assistant on the films Bus Stop (1956) and The Prince and the Showgirl (1957). Feeling disillusioned by conventional methods of filmmaking that required take after take, he turned to documentary and began working with Albert in 1957 on Russian Close-Up and Youth in Poland.

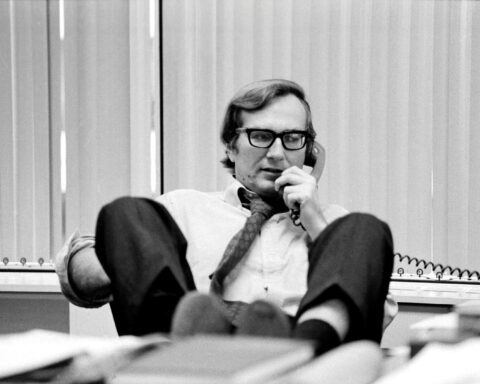

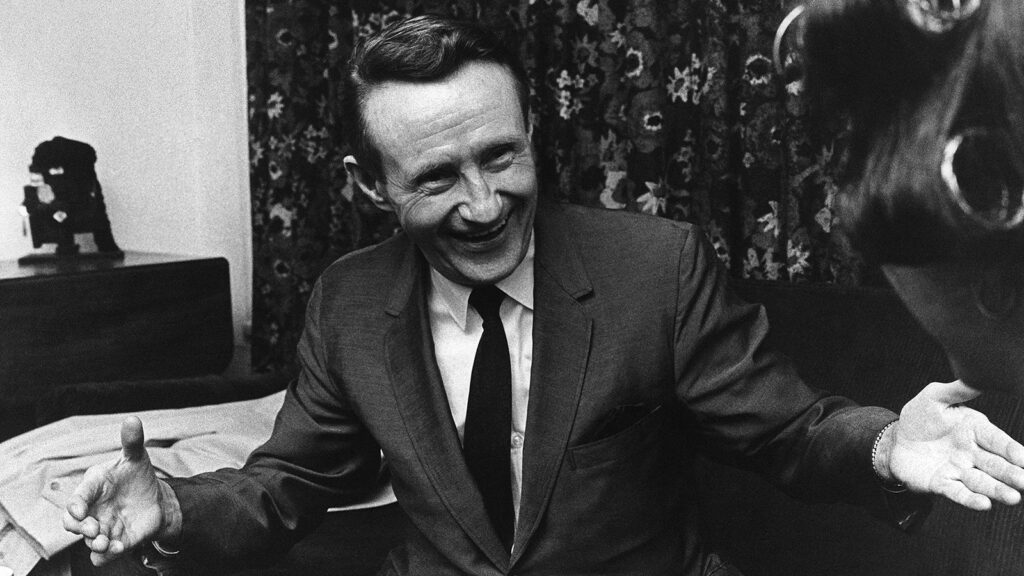

After Albert’s involvement as a cameraperson on Robert Drew’s breakthrough direct cinema Primary (1960)—a project that introduced new possibilities for documentary as a result of technological developments in lightweight cameras and synchronized tape recorders—the brothers reunited in 1963 for Showman, which follows distributor Joseph E. Levine from his New York and Boston offices to Cannes Film Festival to the red carpet at the Academy during the promotional campaign for the Sophia Loren/Vittorio de Sica film Two Women (1961). A voiceover with a certain lyricism carries across the film, first exalting Levine’s profile and successes, then interjecting minimally to provide context between changes of setting. Displaying his dealings with matters to do with publicity, marketing and business, the Maysles survey the vast operations and responsibilities that fall under Levine’s portfolio, demystifying a line of work that remains rather opaque to this day. Although the narration adds a layer of editorialization, which deviates from more familiar conceptions of direct cinema, their next venture, Salesman (1969) saw a development that resembled later iterations of the style. At feature length, the film offers the time and space necessary to reveal characters through their conversations, actions, and experiences, prompting viewers to draw conclusions of their own about the American dream.

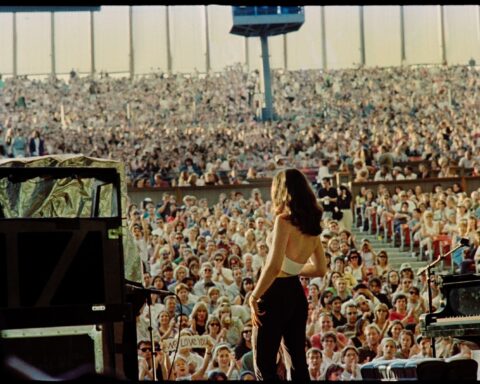

As the two formalized their partnership, they left Drew’s production company to found their own, and created a legendary pairing. Albert and David discovered a unique rhythm and became close collaborators, working together on candid portraits of artists and big personalities such as Gimme Shelter (1970) and Grey Gardens (1975). Up until David’s death in 1987 at age 56, their relationship was sustained by their complementary skills and ability to agree upon everything, a combination that landed the brothers as a pair of the most influential filmmakers in the history of documentary. “We were a natural combination. We didn’t have competing roles. I did all the camerawork, he did all the sound,” stated Albert in an interview.

Reaching further back, the origins of documentary can be traced to the siblings whose contributions exist at the origins of cinema itself: Auguste and Louis Lumière, born in 1862 and 1864 in Lyon, France. Like the Safdies, the Lumière brothers felt a profound influence from their father Antoine, a photographer and entrepreneur who emphasized the importance of curiosity and a varied education. With a prophetic last name and an upbringing that embraced the arts and sciences in equal measures, Auguste and Louis were fated to take over their father’s factory and work on developing new technologies for image-making. In 1895, Louis developed the cinematograph, a relatively lightweight, Turner Ross portable device capable of capturing, printing and projecting moving images, and shot his first film Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory.

Despite its straightforward appearance, the film—which depicts the opening of factory gates; a stream of men and women in hats, coats and dresses hurriedly exiting to the left and right side of the frame, with some on bicycles or accompanied by dogs; then the closing of the gates—required multiple takes and involved some degree of staging. Nevertheless, the 46-second black-and-white film was an attempt at recording actuality in the 19th century, displaying the movement of everyday life in a respectful and gloriously pictorial manner. A precursor to the genre, the film’s production methods are exemplary of a documentary’s capacity to evade strict classification, challenging what we understand about truth, immediacy and the director subject relationship. Despite successful public screenings of their early films, Louis ceased filmmaking after 1895 and trained “operators,” who contributed over 1200 films to the catalogue of the Lumière company, allowing the brothers to develop further technological improvements.

Though Louis led the invention of the cinematograph, the production of their first films, and the formulation of various processes from emulsions with improved sensitivity to autochrome (an early form of colour photography), the patents and papers filed were in both of their names, fulfilling a childhood promise that would forever seal their legacies as one. According to a biography by Michel Faucheux, Louis and Auguste, then aged 12 and 14, discovered a cave that opened to the sea while on a vacation in Brittany with their father. Accompanied by Antoine’s photographic equipment, the story goes that the brothers stood facing the waves and swore an oath to work together for life.

Confirming this arrangement, Louis stated in a 1948 interview, “If the cinematograph patent was taken out in our joint name, this was because we always signed jointly the work reported in and the patents we filed, whether or not both of us took part in the work. I was actually the sole author of the cinematograph, just as he was on his side the creator of other inventions that were always patented in both our names.” While the brothers would retreat from the film industry in 1905, parting ways to pursue other scientific interests—Louis’ in physics and optics, and Auguste’s in biology and medicine—it was clear that they operated in tandem, their desire to work together as well as their creative and technical aptitudes fueling their collaborative relationship for over two decades.

To this day, the possibilities of documentary form and technique are being pushed, pulled, bent, and stretched in far-reaching directions and throughout, inspiring works that blend elements of fiction and non-fiction. In 2023, brothers Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross premiered Gasoline Rainbow, a distinctive entry into the American road trip genre for its use of first-time actors and heavy improvisation in constructed scenarios. A coming-of-age crusade that celebrates the freedom and ecstasy of adolescence, the film follows the escapades and stunts of five high school graduates from Wiley, Oregon in search of a party billed as “the End of the World” on the Pacific coast. Backdropped by the vast desert landscape, the teens reveal their epiphanies and revelations about youth, hopes and anxieties about adulthood, and personal struggles involving addiction and deportation in their families.

Their first explicit venture across the threshold of fiction, the Ross brothers’ previous efforts were grounded in documentary with observational portraits of American life spanning across Ohio, New Orleans, Texas and Nevada in 45365 (2009), Tchoupitoulas (2012), Western (2015), and Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (2020). Working outside conventions that dictate a film should be slick and polished, the pair have developed a signature style of crafting films, which are handmade, tactile, and raw, contain evidence of the filmmaking process, and often prompt viewers to ask during Q&As whether a scene is “real.” While questions about staging arrive naturally with their tendency to embrace hybridity, the two possess an appreciation of authenticity located not in mere documentation, but a quality rooted in experience, time, and place, regardless of whether it’s observed or induced. On Gasoline Rainbow, this shared understanding allowed Bill and Turner to assemble separate cuts with the trust that the other shares common ground, then distill what was essential to each version before working on the edit collectively.

While both are credited as the directors and producers of each work, the Rosses have stated that some films do belong to one more than the other, with Western as an example of a project that found its captain in Turner, whose passion for the idea moved Bill. Prior to Gasoline Rainbow, there was a further division where Turner primarily managed production, while Bill spent time on post-production. But regardless of their division of labour, what matters most to the visionary pair is the pleasure of spending time together and building upon their relationship: “We’re sticking together because we enjoy each other’s company. And this is a shared language and something we’ve built, and it’s challenging, but it’s made our lives so much better,” Turner has said.

There are, it seems, as many ways to exist as collaborators as there are ways to exist as siblings. With diverse beginnings, abilities and roles, documentary has observed a number of siblings entangle their familial bonds with working relationships as creative accomplices. Though the period of collaboration varies from pair to pair, it’s evident that the sibling directors who find success have in common shared histories and perspectives, as well as distinct but complementary skills and interests that can be unified to produce a singular, cohesive sound that pierces through the noise.