“It was just a summer job for them,” says director Bill Ross IV on casting the teenage stars of Gasoline Rainbow. “None of them is aspiring to be an actor, or they weren’t at that point, and it was an adventure. It was a just cool summer job. They genuinely wanted to do that.”

The Ross brothers, Bill and Turner, once again prove themselves the Coen brothers of hybrid cinema. Much like their previous works Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, Western, and Contemporary Color, Gasoline Rainbow explores the space between fiction and non-fiction by observing a cast of non-professional actors in their everyday setting. The brothers let the cameras roll, capturing the stars’ natural reaction to events as they play out. The authenticity of people and places fuels the story. The film furthers the Ross’s distinct body of work with a fine eye for the American West. It casts a quintet of high school graduates in an all-American rite of passage: the road trip.

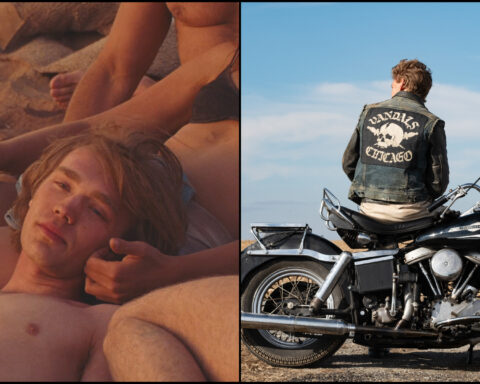

Gasoline Rainbow hitches a ride with the kids as they become adults in this offbeat coming of age journey. The stars—Tony Aburto, Micah Bunch, Nichole Dukes, Nathaly Garcia, and Makai Garza—let the brothers be their guides for a fateful summer in hangout-and-chill mode. The film’s episodic structure follows the kids as they get from point A to point B without much of a plan. Along the way, however, they encounter a cast of colourful characters—hitchhikers, random dudes going to parties in the bush, and the like—while unexpected twists force their journey down dramatic turns. Aesthetically, it’s the Ross brothers’ most beautifully shot film with handled cameras harnessing magic hour sunlight perfectly to capture these young people on the cusp of adulthood.

The film lets audiences spend two hours in the twilight of youth. It’s an immersive experience of what it feels like to be young, carefree, and travelling the world with nothing but the open road ahead of you only to realize that one eventually has to wake-up and see the horizon. Gasoline Rainbow may be the Ross brothers’ most mature film yet as it seamlessly straddles genres and generations. It’s a mellow journey well worth taking.

POV spoke with the Ross brothers via Zoom ahead of the MUBI release of Gasoline Rainbow.

POV: Pat Mullen

BR: Bill Ross IV

TR: Turner Ross

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: Has your way of making films become looser or more structured as the years and projects have gone by?

TR: I think one begets the other. They have become much more composed in terms of initial structure. What we’ve found in the last two projects, the more that we have composed the world, the more loose we can be within it and the more free that our collaborators can be within those situations.

BR: The idea dictates the approach and it just so happens on the last two, they needed a framework in order to pull it off. But it just depends.

POV: In Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, you created the bar of the Roaring Twenties. How authentic were the sets and locations in Gasoline Rainbow? Was this an ordinary camper van you were shooting in, or was it designed to fit the kids and the camera and you guys?

BR: We got the van a couple days before we started shooting. While we were scouting or casting, we’d be on the lookout for the right van, whether it would be for sale by the side of the road. It was not a picture van. It needed to be real. We needed it to feel like something the kids would have. I don’t even remember where we found it. All locations were real locations, but like Bloody Nose, they were set up for us to do what we needed to do.

TR: Just like the characters, there’s a veneer of artifice, a little bit of preparation, but not much. Bill and I scouted the world first and built out this path. It makes logical sense in terms of the landscape and a potential journey. Along the way, we found places that belonged within those worlds that would be conducive. Some of them required a bit more preparation than others, but primarily, it’s the real world. This a crew of seven people in an RV following a van and shooting every day linearly until we reached the end.

POV: How does it work when you’re making some of the big narrative beats? Say when the kids are out and they come back and the wheels are stolen from the van, do they know that’s happening?

BR: We made a promise to the kids and their parents that no matter the situation, they would be safe and they would be taken care of. But they did know that there would be surprises along the way. So, yes, while one of us is off shooting with the kids, the rest of the crew might be taking the tires off the van or getting cowboys to herd horses across the road.

TR: We try to keep any sense of production outside of the line of sight of people who are on the other side of the camera so that their experience is unencumbered by all the trappings of how it’s made so that they can be truly present in their situation.

POV: That scene with the horses is really great. The natural reactions are so wonderful and innocent. I understand that this was your first film working with a casting agent too?

BR: They were our friends. It sounds more official when you say “casting agent” but –

TR: They were two friends from New Orleans who started a casting agency and were our boots on the ground in the northwest while we came and went. They did street casting for three months, going through hundreds of faces and interviews and photos and documentary-style stuff because we’re also writing while we’re casting. We want to feed off of the real experience and the actuality of what is there, not the preconceived idea, so the casting changes as the writing changes and back and forth.

Ultimately we landed on these five, it could have been three, could have been one, could have been more like The Wizard of Oz. A lot of the marquee characters that they meet along the way were cast while casting locations, out of those spaces so that they spoke inherently from that world. It was the middle of the pandemic and we were trying to cast high schoolers as guys in their forties, so it seemed like we could use the hand…

BR: We would have been hanging out in high school parking lots.

POV: That’s kind of sketchy, I guess.

BR: Yeah, a little bit.

POV: Were there certain qualities in the teenagers? Or were you looking for the right people who had a good vibe together or the right look for the story?

BR: It needed to be kids that would do something like this. That was number one. But they’re each magnetic in their own way and each person needs to be a unique individual with a story to tell who would readily engage with the world and the scenario.

Then it comes down to dynamics. We met a lot charismatic people. This could have come out many different ways, but in the end, we had to have a really strong dynamic. They needed to move out into the world as an entity with no duplicity, each one a unique character and within the dynamic be interacting and having their own unique stories, but also bringing those out into the world. We’re relying on people not to perform or to invent too much. These people have to be movie stars of life. They have to pop out in the world and each speak well for their own experience because they’re bringing a lot of themselves. Even if there is a layer of artifice, they’re bringing a lot of themselves to the experience.

POV: Was there a learning curve in terms of how teens today speak and carry themselves in the world?

TR: They can’t help but be themselves, so we just had to follow along. So, yes, every day we were learning a lot. Whether it be terminology—

BR: “Deadass.”

POV: What?

BR: They said the word “deadass” a lot, which was, at that point, new to me.

POV: Well, I learned a new word today.

TR: They treated it in their own way. They treated it professionally. They understood what this was.

BR: It was interesting, the perception between the ages. This was the first time I’d been referred to as “Mr. Turner.” I hadn’t felt old until then. That was interesting. But we had a really great cohesive team. It’s what made it work—a lot of interpersonal relationships and being there for each other off screen.

TR: There really wasn’t a separation. We were together 24 hours a day and we really were like a travelling family circus. We all had to trust each other, depend on each other, and I think we all learned things from each other.

POV: When you’re working with non-actors, are there cases where you’re taking direction from them? How does the story adapt to their reactions to a situation?

TR: It’s all dictated by them once the camera starts going. If anything feels inauthentic, we know we’re on the wrong path. Mostly, we are creating the condition so that we can just follow that. We can be observers and mildly push things in certain directions. But if there’s ever anything that they overtly baulked at, and I can’t think of many instances, then it’s going to end up being performance and that’s not what we want. They’re there to have an honest experience in whatever way they see, but not to perform, not to do our bidding.

POV: Are there second takes when you’re filling or do you shoot as you go and get what you get?

BR: The hope is that there’s never second takes, and I don’t think there were any in this film.

TR: There aren’t even really takes. There’s no “action” or “cut.” We try to make sure it never looks or feels like a film set.

BR: Once the day begins, it just goes and it doesn’t stop until we have to.

TR: Bill and I are the only ones who know what beats need to be hit and what we need to get out of each scenario. If we’ve been after something for several hours and we’re not getting where we need to go, we might need to reset and regroup.

BR: There might be a prompt, like “alright guys, consider…” or “let’s move on to this topic,” or something like that. But no second takes. When we’ve tried that in the past on other films, you don’t use it. Especially with these guys, you break that wall. It is noticeably different. Once you break that energy, it’s unusable.

POV: How does that affect the edit if you don’t have multiple frames of coverage for a scene?

TR: We’re both shooting all the time. There’s always cameras on everything.

BR: It affects the edit majorly because you just get what you get.

TR: Sometimes it’s the only time it happened. But other times, we’re in a scenario for 10 or 12 hours and it’s going to be a two-minute scene, so those pieces are going to be there. We just have to be present for it to unfold, mostly not to fuck it up and just capture, to be there for the moment.

POV: You do that really well in the scenes where they’re running with the trains and hitching a ride in the cars. How did you pull that off? It looks quite risky, but I assume there was a production to it.

TR: There was a lot of external choreography that sometimes is unseen by the cast and always is unseen by the viewer. Situations might be multiple setups, multiple days of shooting with safety parameters. There’s a lot going on offscreen, not only for safety and legal, but because we had such a tight schedule and a low budget, there was only one shot to do any of these things. When you’re doing wild shit like that, it has to happen and it has to work. We had to do a lot of pre-planning to make it feel organic. They were never in any real danger.

POV: But it’s really convincing in the way it is shot. It feels very clandestine. I was expecting a security guard to come tearing out and start yelling.

BR: Some of that thread is still there!

POV: The post-graduation road trip is a coming of age ritual and you were there to see these kids go through that in real time. What was that experience like? By observing youth, what did you learn about growing older?

BR: It was really cool to see them have these new experiences and learn. This older person would have this knowledge of how the world can work, and they’re like, “oh, okay” in real time. And you can be different and that’s fine. There were a lot of days like that. It really felt cool to witness that moment.

TR: That epiphany was very real for them. It was a crazy gauntlet for us, and we were different on the other side, so it was a mutual experience.