If you’ve seen Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies, you’ve met Jim. And probably never forgotten him.

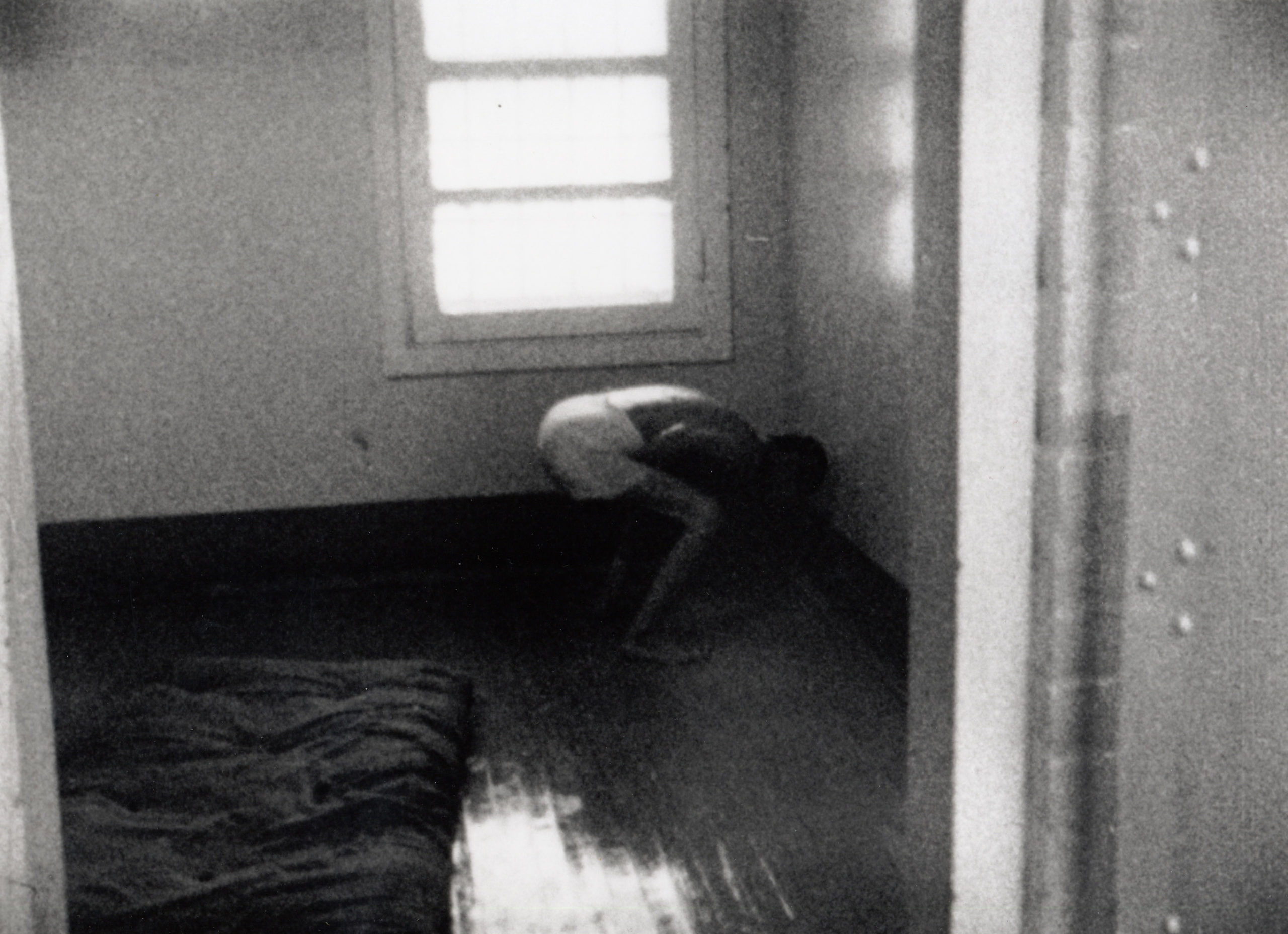

Jim is the man in the movie, shot at the Bridgewater State Prison for the Criminally Insane in 1966, who got Wiseman into a lot of trouble. Kept in solitary confinement for 17 years, Jim is seen in the film enduring what we can only interpret as a daily routine.

Like most Bridgewater patients designated dangerous to themselves, Jim is kept naked, and that is how he appears as he’s taken for a shave, a hose-down passing for a shower, force feeding through a tube inserted into his stomach through a nostril, and relentless reprisals from staff over the issue of keeping his room clean. (This we assume is a form of inside professional humour, as Jim’s room has nothing in it to keep clean.)

Throughout this ordeal Jim, identified only as a former school teacher, does his best to keep his temper intact, and we can tell from his demeanour—he pounds the floor in rhythm with his bare feet; holds his temper in check despite ample provocations to lose it; swings emotionally between resignation and indignation—that Jim is a man who has put up with a lot. We don’t know how many years he has been experiencing the kind of internal disturbance that landed him in Bridgewater (though the term “criminally insane” suggests he’s not there for just talking to himself ), but we do know, based on what we see of this day in Jim’s life, that 17 years at Bridgewater may not be the best way to get one’s mind in functional working order.

That’s what makes Jim’s resilience all the more remarkable. Inspirational, even. Throughout the blunt grooming and feeding session, Jim vacillates between chatting with and cursing his handlers, shifting from Tourette’s-style rage outbursts to chatty bonhomie about matters like the weather. The staff clearly gets a rise out of him—one guard revealing a particularly persistent determination to get poor Jim as pissed as possible—and everything in their manner conveys a certain bored overfamiliarity with Jim’s eccentricities and responses. He’s being goaded because he’s so obviously goadable—“What’s that you said, Jim?”, “How come your room is so dirty, Jim?” The doctor we see administering the feeding tube, who is elsewhere heard explaining to inmates how hopelessly crazy they are, is so nonchalant he smokes while pouring Jim’s dinner into the funnel attached to the tube.

But listen to Jim when he’s asked if he wants to take a drink from the water fountain. Naked, he leans over the spout and, just before wetting his mouth, which we see bleeding from the shaving razor, he lets fly with this: “On the house, is it?”

The one-liner doesn’t get much of a laugh, either from the guards or from us in the audience, particularly if we’re seeing Titicut Follies for the first time. The movie’s a little too intense for that. But if you can get the distance required to appreciate the irony, Jim’s crack comes not only as a welcome riposte to the brute treatment he’s getting, but a genuinely stirring sign of life, intelligence and spirit. It suggests he knows exactly where he is and how it works; that he’s probably considerably smarter than his keepers and tormentors; and that there’s a certain level where Jim is only as crazy as the circumstances he’s in. In that moment especially, the very idea of madness shifts from something afflicting Jim to something afflicting Bridgewater. That the shaving sequence is intercut with images of Jim being prepared for burial, and being treated with far more dignity in death than he was when alive, could not have gone down easily for people worried about their careers. And that’s how Jim got Fred Wiseman into such deep shit.

A young law professor at the time, Wiseman got the idea to film a documentary at Bridgewater while taking students there to observe how a state mental institution worked—or didn’t, as the case may be. He went through what he thought at the time were the proper channels, requesting permission to film inside the facility and agreeing only to shoot when he was given a verbal okay by the staff. It was they who determined whether a subject was fit for filming by Wiseman, they who held ultimate power over whether or not the treatment of a guy like Jim was suitable for public consumption. And they decided it was, at least until somebody higher up actually had a chance to see Titicut Follies and be suitably and reasonably appalled. Nobody in the film looked nearly as bad as the hospital and its staff did, and nothing in the film made the hospital and its staff look quite as bad as Jim’s morning shave, shower and liquid meal.

And so the troubles began. Mortified by the final cut, state and institutional authorities sought to block the film on the basis that it violated the privacy of the inmates, and especially Jim. The verbal agreement Wiseman had reached was deemed irrelevant and insufficient, and Titicut Follies was banned from public screening or distribution until 1991. It was said to be the very first movie banned in America for reasons other than obscenity or national security.

In justifying the decision in 1968, Massachusetts judge Harry Kalus wrote that Titicut abounds in: “crudities, nudities, and obscenities. 80 minutes of brutal sordidness and human degradation. A hodgepodge of sequences, the camera jumping helter-skelter. There is no narrative, each viewer is left to his own devices as to just what is being portrayed.” Therefore, “No rhetoric of free speech and the right of the public to know can obscure this [picture] for what it is: trafficking in human misery, degradation and sordidness of the lives of these unfortunate humans.”

As Wiseman recalled nearly 50 years later, “Eventually there was a trial in Massachusetts. The most important issues at trial were, first, that the film was an invasion of privacy of the man who’s shown naked in his cell, and, second, that I had breached an oral contract giving the state editorial control of the film. At the time the film was made there was no right of privacy in Massachusetts. The judge, for the first time in Massachusetts’s history, found a right of privacy to exist. On the editorial control issue, [then-Lieutenant Governor and future Watergate player Elliott] Richardson simply asserted it. Neither I nor any other filmmaker, unless we were completely mad, would have ceded editorial control to three people who knew nothing about filmmaking.”

Among the things evidently not known about filmmaking, at least among those offended or horrified by Titicut Follies, is that the camera only records what happens in front of it, so what one does in its presence will be recorded and, if pertinent to the emerging narrative during editing, is there to be seen and possibly to provoke a reaction. Apparently oblivious to how the conduct of the staff at Bridgewater might be interpreted by viewers, the authorities whom Wiseman has always insisted had granted him permission suddenly nullified the arrangement and sought to have the movie almost entirely blocked from public view. (In the original ruling, the film was deemed acceptable for screening only to professional groups.) While a certain naiveté on the part of the Bridgewater staff participants might be attributed to the fact that Wiseman and his tiny crew were using equipment small and portable enough for the filmmaker to slip in and out of situations more or less unobtrusively, we might safely venture that something very different from concern about the inmates’ right to privacy was at work. Like the privacy of the staff, who were caught doing what they presumably do every day. That, and the impact on viewers of seeing someone like Jim.

What Jim’s presence in Titicut marked was something almost unprecedented in documentary film up to that point: a person afflicted by mental illness who was being looked at without judgment, flinching or the convenient distancing of clinical categorization. Jim, as naked and vulnerable as a man can be, is presented in all his stark idiosyncrasy. Yes, he is clearly someone with severe clinical issues, and yes, he would seem to qualify for most people’s idea of what it looks like to be mentally ill. But what Wiseman gets to with his careful presentation and contextual framing of Jim is a sense of what it feels like to be in Jim’s situation. By looking so closely at Jim in his literal and figurative nakedness, we are compelled to consider and accept him as a human being subjected to grotesquely unfair, insensitive and most certainly traumatic treatment. And by making Jim such an absorbent figure for the flow of our empathy, Titicut Follies became a movie about something very different than anyone at Bridgewater or the Massachusetts state government expected or were prepared to accept.

Instead of offering a portrait of a system working to address a problem, Wiseman had made a movie about how badly vulnerable and sick people were being treated by their own government. He’d made a devastatingly effective movie that showed mentally ill people being treated like animals. Worse, he’d made a movie that suggested the real animals were the staff, while the real people, in the sense of being so flagrantly worthy of our sympathy and outrage, were the poor souls who found themselves locked up at Bridgewater. This was One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest without the fiction or implied redemptive catharsis. Or Planet of the Apes stripped of allegory. This was something that had actually happened somewhere, and there was no redemption in sight.

It is an incalculable pity that Titicut Follies was so inaccessible to so many for so long. Like Allan King’s contemporaneous, equally verité and also banned Warrendale (also about questionable, but considerably less medieval, institutional practices), Follies’ influence as both an exposé and a documentary milestone has been diminished by the limitations placed on it by being aborted from its context. Had it been available to wider and less professionally interested audiences, the film might not only have hastened the reform of facilities like Bridgewater, it would be accepted for the landmark it was in terms of the documentary treatment of the mentally ill.

What Wiseman found in Jim was a figure so compelling in terms of insurgent human will, and yet also so clearly afflicted by powerful mental disorders, you couldn’t help but feel his struggle. You couldn’t help but wonder what 17 years of this treatment must have done to Jim, or what it might do to you. You might even wonder if you would have what it took for Jim to stay alive that long. (I know I wouldn’t.) But such wonderings are why Titicut Follies remains as provocative and pertinent today as it was 50 years ago. Even leaving aside the fact that the conditions visible in the film remain largely intact and unchanged in an alarming number of places around the world, Wiseman’s movie still holds you by the throat by sheer force of empathy: it was the first movie to look so nakedly (so to speak) at madness but with such astute sensitivity to the human beings beneath. Besides, it then reasonably asked, who’s really crazy here? Is it Jim? Or is it a system too deluded to even see itself?

Titicut Follies is available on DVD from Zipporah Films and will soon be available on Kanopy streaming.