The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart

(USA, 110 min.)

Dir. Frank Marshall

Frank Marshall has produced some of the biggest blockbusters in cinema history, including the Indiana Jones and Back to the Future franchises, and shaped many extraordinary non-fiction features throughout his decades-long career. With The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart, he takes the helm of a feature doc for the first time as a director, telling the remarkable story of how three brothers left their homes in Australia to conquer the music charts.

The story of the brothers Gibb has been told many times before, with Marshall’s film drawing significantly from interviews conducted for Martyn Atkins’s 2010 film In Our Time. We learn about the young lads who emigrated from England to Oz, were pushed to the stage by their supportive father, and then returned following local success to try to catch the eye of Brian Epstein, the same musical guru who managed the Beatles. Parlayed to Epstein’s employee Robert Stigwood, the trio would find almost immediate success thanks to their beautiful harmonies and Lennon/McCartney-esque melodies.

After their initial chart topping, the three brothers—Barry, Maurice, and Robin—grew apart, only to reconcile and find a new sound at Miami’s Criteria studios. Here they’d help launch the disco sound to stratospheric heights, only to be caught up in the backlash that ensued.

If this was all the film showcased, it would be a fine if placid biographical film and a run-of-the-mill remembrance of this era of music. What sets the film apart, however, is Marshall’s clever incorporation of contemporary artists reflecting not only on the legacy of the Bee Gees, but on how certain key elements of their story – siblings working together, the nature of backlash after success, etc. – are far more universal than may first be expected.

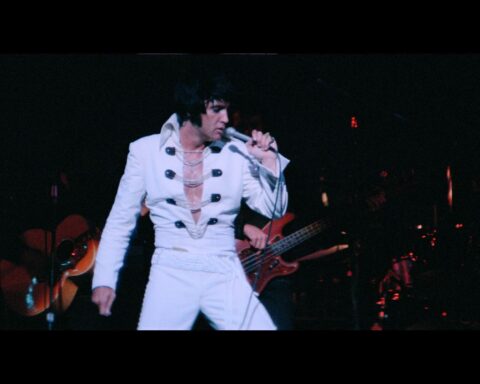

The film begins with Barry Gibb, the sole surviving brother, on the grounds of his Miami home. His long hair is grey and thin on top, but his eyes remain sharp and his voice strong. “I am beginning to recognise that nothing is true,” he intones. “It’s all down to perception.” The perception of the Bee Gees has always been couched by their grand success with Saturday Night Fever. The soundtrack became a phenomenon, and remains one of the highest selling records of all time. Yet the band was much more interesting than the one explosive hit, and their continuing relevance and legacy is far richer than may first be understood.

Marshall’s film provides a decent-enough overview of the biography of the band, but it’s even more fascinating as a tale of ambition and hubris instead of the simple pop story it could have been. The dynamic between successful brothers is nearly biblical in its mythic status, and it’s easy to find correlation with other groups that went through similar turmoil, from the Kinks to the Beach Boys, the Osmonds to the Jacksons. It’s all the more revealing. “When you’ve got brothers singing, it’s like an instrument that nobody else can buy,” claims Noel Gallagher who shared the band Oasis with his brother. Working with siblings is “the greatest strength and the greatest weakness you can have” in a band, and it’s this paradoxical nature that Marshall’s film keenly illuminates.

Nick Jonas, another musician famously from a band of brothers, speaks from a place of understanding. He talks about the “complicated” nature of finding great success with the people one grew up with. Each interviewee speaks as a fan of the Bee Gees, but also sees within his or her travails the band’s own familial challenges and how the regular jealousies within any group are exacerbated when members share a family bond.

Eric Clapton helps take credit for sending them onto Miami. Justin Timberlake makes a strong case for how their vocals were like horn lines, joking that he’s not intoxicated while making that (valid) claim. Chris Martin from Coldplay speaks about the nature of backlash, and how there’s a now accepted cycle that with the rise to pop superstardom, the cynicism and attacks will be amplified. With the Gibbs, this vitriol was relatively new, and the bile and hatred of the “Disco Sucks” movement, which was often fuelled by homophobia and racism as much as musical taste, complicates the narrative even further.

It’s these more philosophically rich elements that raise Marshall’s film above the fray, resulting in a genuinely probing and profound look at this remarkable group. The brothers were in a constant state of reinvention, and the film does wonders to establish them as songwriters and craftsmen rather than simply riding a fad. The studio experimentation and connection to some of the production icons of the era such as Arif Mardin firmly establish them at the forefront of defining the sound of that era, yet the band never neglected to champion the African American artists from whom they drew so much inspiration.

It’s telling what’s been left out of the story – a single frame of the band holding up a platinum record references their Sgt. Pepper musical movie, a schmaltzy production that nonetheless further solidifies the connection between the Bee Gees and the Beatles. Additional tabloid elements are glossed over, and it would have been remarkable to hear from the likes of Barbra Streisand or Dolly Parton directly. It would have been interesting to hear Barry Gibb in his contemporary interview dive more deeply into the causes of the backlash, how they may have taken the oxygen away from other artists who helped establish the sound, etc.

In the end, we’re left with something far more than a traditional rockumentary. We’re left with a celebration in the best sense. The film grants new listeners the ability to be wowed with the breadth of output, and old fans can reflect on the band in a new light. We’re invited to look beyond the glitz and gloss and find musical sophistication that continues to resonate with contemporary productions. Marshall’s present this story with great musicality, taking seriously the craft of what was done rather than focusing on the betrayals and backstabbing.

It’s hard to think that a band with this level of enormous financial success would be in any need of resuscitation. However, Marshall’s film makes a strong argument that beyond the poppy and punchy dance beats, the Bee Gees were a group of sophistication and seriousness that’s been overlooked by many with layers of intrigue that surpass their specific story. The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart is a specific yet universal tale that excels amid a sea of formulaic contemporaries, delivering a poignant, profound examination of some of the most enduring songs from the era.

The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart is now streaming on Crave.

1