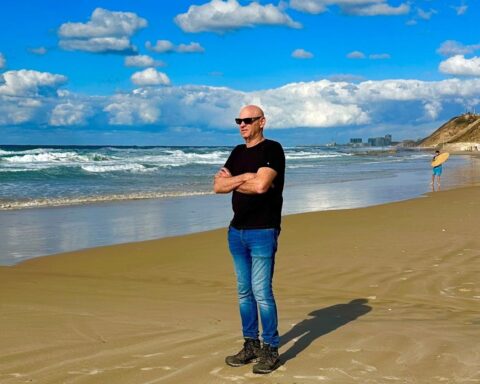

Larry Kent was the first feature filmmaker to make English-Canadian movies with the urgency of the European new waves of the 1960s but his work was barely seen by audiences and ignored by critics and, later, academics. Fifty years later, however, Kent’s pioneering Canadian independent films are screened at retrospectives — The Bitter Ash (1963) was shown at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival — and a remake of his Hastings Street (1962) will soon be released. And Kent is the same irascible independent looking forward to another Vancouver shoot.

Back in the 1960s, this country was so prehistoric, cinematically speaking, that the first Canadian feature Larry Kent saw was his own Bitter Ash.

***

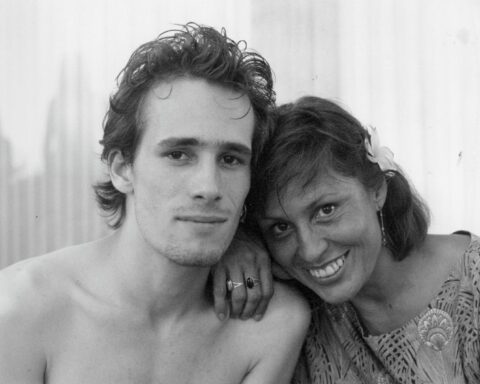

A young South African exploring the world in 1957, Kent’s planned stopover in Canada lasted a lifetime longer than he anticipated. He married, found work as printer at the Vancouver Sun, and enrolled in UBC’s (University of British Columbia) theatre department. As a child, Kent had whiled his days in movie houses. When he arrived in Canada his dream was to be an actor, not a director (“I think that Brando and Dean and Paul Newman were far more influential on me than directors,” he has said), so he became an actor’s director. “At UBC, I wrote an anti-Apartheid play which was very successful. But I just felt that the stories I wanted to tell didn’t fit the theatrical. I was in love with movies.”

There were virtually no crews or equipment or film actors in the city, but Kent met CBC cameraman Dick Bellamy and with an adventuresome cast from UBC — including Alan Scarfe, Patricia Dahlquist and Scott Hylands — set about shooting the short film Hastings Street, a tough Skid Row crime story. “I suddenly became aware of directing while I was making my first film.”

***

This August 2012 day in suburban Richmond, Kent-philes have assembled to re-make Hastings Street, which was shot in 1962 but because of sound and financial issues not released until 2007.

Vancouver independent mainstay Tom Scholte did one of the new voice-overs for the original Hastings Street and plays a cop in this feature version, which is being made by former Vancouver Film School colleagues of Kent. “This is like a cult of Larry,” says Scholte. “They adore Larry. He’s absolutely genuine and his tenacity is so infectious. Everyone who comes in contact with Larry is changed.”

Scholte first teamed with Kent for 2005’s Hamster Cage. “Larry has become the most important touchstone person in my life creatively now because of his endurance, his ideals, his dedication, his honesty about his own strengths and his own weaknesses. He is someone that in a moment of doubt I will talk to.

It’s not about follow the Larry Kent road to success because Larry has been a marginal and marginalized character in a lot of ways, and sometimes he’s been the author of his own position. But he gives me great courage whenever I talk to him.”

***

In 1962, Kent caught Lenny Bruce’s taboo-smashing act at the Cave nightclub just before censors cancelled the comic’s Vancouver run. “He didn’t have a hope in hell in Vancouver,” says Kent. Neither did Kent. His first feature The Bitter Ash got the Bruce treatment a year later, banned in the province after a screening at UBC. Although tame by today’s standards, its borderline profanity and semi-sex scenes were just too much for the era’s B.C. censors.

Prudish moralism defined Vancouver in the early 1960s. Since English-Canada had no feature tradition of its own, it was fortuitous that the pioneering filmmaker happened to be one in love with the French New Wave and Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Brando and Rebel Without a Cause. For Kent, taboos were waiting to be broken.

Kent’s Canada of the early 1960s was an urbane place filled with class alienation and sexual frustration and young people bursting to get out of the 1950s: the working-class tough who clashes with Vancouver bohemia in The Bitter Ash, the teenage sexuality of Sweet Substitute (1964), the pre-feminism feminist fleeing a stultifying marriage in When Tomorrow Dies (1965). Kent’s shoots left plenty of room for improvisation and innovation, workshopping Sweet Substitute with only a story outline, a precursor of the filmmaking later made famous by Mike Leigh. “We improvised every scene on audiotape. I went back, edited all the material and rewrote it keeping all of the rhythms.

“How can you be a director if you don’t know how to talk to an actor? There’s so much bullshit I’ve been reading lately that so-and-so’s a great director because he leaves the actor alone. The actor has to tell the story that you both agree to. He or she relies on you. And if there’s trust they can begin to improvise.”

While Kent’s films deal more with personal relations than overt politics, his leftwing views are never far beneath the surface. “I’m a lefty but my films are social documents. They’re about people in society. How people behave. Bitter Ash I think is one of the few films in Canada that really deals with working-class people—working in a boring job but needing to keep the wolf from the table.” A red-diaper baby in South Africa, Kent became a member of the Young Communist League, but was far too independent to accept any party line for long, turning instead to more anti-authoritarian variants of socialism. Had he immigrated to Hollywood instead of Vancouver he might have been blacklisted in the anti-left hysteria of the times. (One of the few advantages of moving to a country that didn’t make movies in the 1950s.)

Banned in most of Canada, Kent did take Bitter Ash to L.A., where he showed the film to Arthur Knight, a noted University of Southern California film professor and author. Knight invited Kent to screen it in a room filled with future filmmakers. “Years later in Toronto, Don Shebib told me, ‘I was at USC when you brought Bitter Ash there.’” Also in L.A., Sherpix, which operated theaters across the U.S., picked up Bitter Ash for its midnight screenings. So Bitter Ash joined the U.S. midnight circuit, where everything from Pink Flamingoes to The Harder They Come would break.

After When Tomorrow Dies, Kent left Vancouver for Montreal, where he remains, but his first four films are a chronicle of the 1960s’ West Coast and pre-hippie hip generation that relished Lenny Bruce, European film, Beat writings, the Civil Rights movement, and folk music. “Those movies have something to say about a time and a place and people. I was very much hated by the establishment. Making a movie on my own was something you didn’t do in Canada. It was anti-Canadian. If you wanted to make a film you went to the National Film Board or the CBC.”

In Montreal, Kent directed High (1967), a counter-culture heist movie that drew the ire of Quebec censors, and The Apprentice, a comic look at crime as a solution to economic woes, with Susan Sarandon in her first starring role. In casting the female lead he held auditions in New York and was in the unlikely position of choosing between a couple of young actresses with a future. “Susan Sarandon or Diane Keaton—and that was a tough, tough choice. I spent two or three days with each of them talking about the project. Both very intelligent, both really good. I hadn’t seen anything of Diane’s but I saw Joe and I really liked it and I really liked what Susan did.” (Read more about The Apprentice here.)

Kent was the first in English-language Canada with the determined, uncompromising sensibility that would come to define independent film, but was soon joined by Vancouver’s Jack Darcus and Morrie Ruvinsky, and Toronto’s Dons (Owen and Shabib) and Davids (Secter and Cronenberg). While never amounting to a Canadian Wave, they created a kind of scattered Canadian ripple in the 1960s and ’70s.

“In 1973, Larry Kent was a heroic figure for me, as a man who had made six(!) actual movies before I had yet managed to make any,” David Cronenberg recalled in 2003. “He had shot them in Vancouver and Toronto and now in Montreal. He was about to make another one. There in the halls of Cinepix I complained to him about the Canadian Film Development Corporation’s reluctance to invest in my proposed first movie, Orgy of the Blood Parasites. He said to me, speaking as though we were holding the biggest press conference in the world, ‘We are young, we are passionate, and we will not be denied.’ I loved him on the spot.”

***

“Bullshit!” Kent shouts in my direction. It’s two years before the new Hastings Street shoot and Kent and I are at the East Vancouver house of Scholte and his actress wife Frida Betrani when the grumpy old director takes exception to something I’ve said about cinema. Minutes later Kent will fall through his chair, destroying one of Scholte and Betrani’s favorite furnishings. Not a great day for Kent but nothing he has done or said leaves any of us offended because while his personality is one part cantankerous, it is also several parts loyal and insightful and bristling with creativity.

The new Hastings Street originated when its director Andrew Moxham met Kent when he returned to Vancouver for a film school workshop in 2004. “It started out by us sort of falling in love with Larry, which is easy to do,” says Moxham. “Either you love him or you hate him, usually a little of both. He’s this old guy who still has the same energy he had when he made Hastings Street. When you watch Bitter Ash or Hastings Street his work is unapologetic.”

Back on the Richmond set of Hastings Street, actress Leela Savasta is apologizing to actor Shane Twerdun, who has burst into her rundown hotel room. “I’m sorry,” says her beaten character, crouched among the full ashtrays and empty bottles. Twerdun takes a sudden punch to the head, collapses on the bed, and the two are ushered into an equally grimy hallway.

Twerdun, who co-starred in Kent’s 2011 feature Exley, and Moxham first suggested Kent remake Hastings Street. But Kent said no. “The film is 50 years old. I think he’s kind of over it,” says Moxham. So Moxham (directing) and Twerdun (acting and writing) went ahead. It’s the first remake of a Canadian film, taking intriguing short-film characters to their feature-length fruition.

For Twerdun, it’s all a matter of following the Kent no-budget template. “He’s mentored us. It’s passing the baton. It’s the film where you max out your credit cards. This is the one.” Younger Vancouver filmmakers aren’t the only ones inspired by Kent. Some of Toronto’s best have paid tribute to the director and his films, including Don McKellar (“pretty great”) and Atom Egoyan (“so ahead of their time”). Kent’s contemporaries have fond words too. “We were like twins,” says Quebec’s Jean Pierre Lefebvre. “We always admired each other.”

***

Kent had early chances to move on, including an offer from Roger Corman (“I never ever could listen to a producer. He was a hands-on producer. I would have been fired in one day.”) and talks with Jack Nicholson about shooting a film together after the actor saw Kent’s work. “He said, ‘Okay, but I’m going back to make a film first.’” Turned out to be Easy Rider. Everything changed for Nicholson and Kent couldn’t get the funding to proceed with their joint project.

Kent had no interest in pursuing Hollywood studio work and had a young family in Montreal. He moved from day jobs at the NFB and the Montreal Gazette composing room, while continuing to cobble together movie projects. Kent was a hired-gun on several Cinepix productions, including This Time Forever and Keep it in the Family, but he couldn’t bear working under the thumb of producers. “I said I’d never do it again. Producers are continually putting stupid ideas into a film because they think it’s commercial. I thought, ‘Fuck you, it’s not your money anyway.’ It was Telefilm’s money.” So he worked outside the film industry on purely independent projects such as 1992’s Mothers and Daughters.

In 2002, Kent came back to the West Coast for a Vancouver filmfest screening of Bitter Ash, and he was rediscovered by a new West Coast Wave of independents, including Scholte and Bruce Sweeney. “It was a magical event. People welcomed me and still do.” He put together Hamster Cage, about a scarily dysfunctional B.C. family, combining his old ensemble (Scarfe, Hylands and Dahlquist) with a new generation of Vancouver actors (including Scholte, Jillian Fargey and Carly Pope).

“It was great,” says Scholte. “I mean, it was madness, but I got to do things as an actor on Hamster Cage that I wouldn’t have normally done because he pushed me out of things that he’d seen me do before and challenged me in ways that were unique. Just being around his energy, commitment and drive, and the other actors I got to work with was phenomenal.”

The father of Vancouver cinema has no doubt about the character of Canadian film. “If you put a Canadian film on I know immediately it’s Canadian. There’s a kind of shooting that’s in a Canadian film, there’s a kind of sound recording that’s uniquely Canadian. I don’t know if it’s good or bad but it’s there. There is something unique about Canadian themes. A lot of Canadian films are closer to Scandinavia than they are to the Americans. The alienation and coldness of the northern country brings out a certain kind of human being. There’s no doubt about it. Much more inhibited, much more alienated, and you see this in both French and English film. We sort of have two kinds of films—quirky, very sort of avant garde and naturalistic, very sort of cold movies.”

He has no doubt either about the problems of Canadian cinema. “We weren’t given screens then and we aren’t given cable now. Cable television should be the staple of getting film off the ground but it’s only interested in one thing: dumped product from the Untied States.”

While Kent is a cinephile in love with European waves and old Hollywood, he has always been more about the future than the past. And he’s excited about the movie-making revolution that’s in the works. “I love it. People can make films easier, people can show them easier.”

Adds Scholte: “Not only has Larry got a sense of history but he’s the most current film-watcher I know. He’s sees everything and every Canadian film. He’s not going, ‘Ah, the kids these days.’”

In the Canada of the early 1960s there was no option but independent filmmaking and it’s that independence that’s kept Kent vital. Now he’s set to return to Vancouver to shoot another feature, She Who Must Burn, with Twerdun playing a preacher of the radical right.

“I realize I can still be making movies because I never became a commercial filmmaker,” says Kent. “If commercial filmmakers haven’t made it to the big time by their forties it’s over. Younger kids are coming up, there are new styles—-and, well, goodbye. I would have been finished by my forties. By being an independent filmmaker I can go on until I die. That’s why I never regret it. “

Larry Kent filmography

The Bitter Ash (1963)

Sweet Substitute (1964)

When Tomorrow Dies (1965)

High (1967)

Facade (1970)

Saskatchewan: 45 Below (1971)

The Apprentice (1971)

Keep It in the Family (1973)

Yesterday (1981)

High Stakes (1986)

Mothers and Daughters (1992)

The Hamster Cage (2005)

Hastings Street (1962/2007)

Exley (2011)