Love him or hate him, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates is well known for his philanthropic endeavors, while his late friend and former coworker, Ric Weiland, has received significantly less recognition for his noteworthy philanthropic contributions. In Yes I Am: The Ric Weiland Story, filmmaker Aaron Bear sets out to right this wrong, establishing Weiland as a humanitarian and pivotal LGBTQ activist.

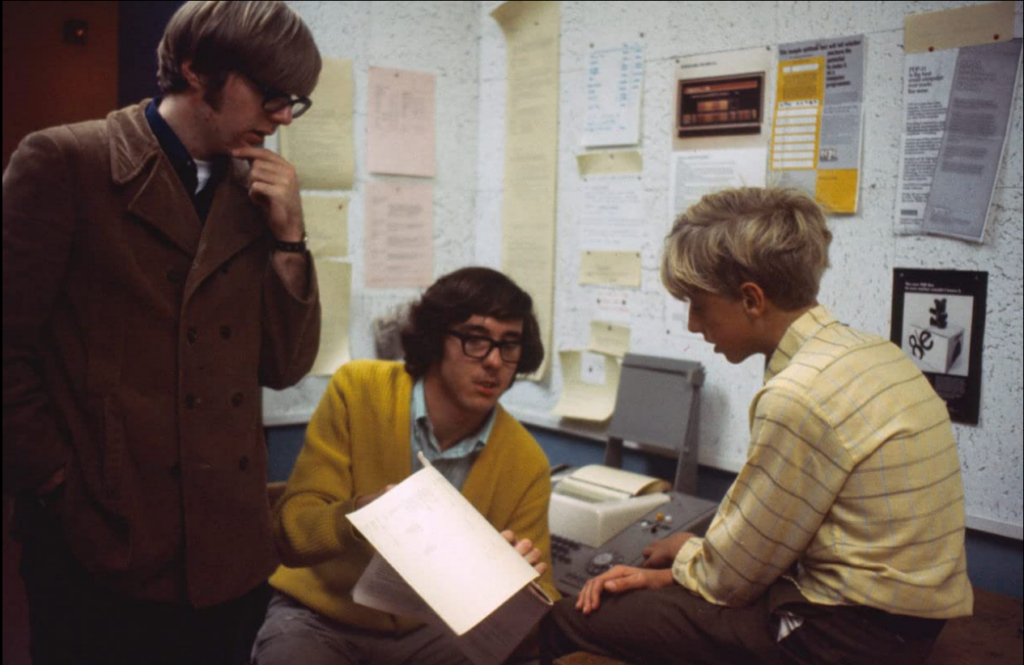

A talented computer programmer, Weiland was one of the first five Microsoft employees. In the tenth grade, Weiland and his friend Paul Allen, along with two eighth graders, Bill Gates and Kent Evans, formed their preparatory school’s computer club, the Lakeside Programming Group. A few years later, Gates and Allen founded Microsoft in 1975 and invited Weiland to join their new venture as a programmer and developer. He briefly left the company to attend a few semesters at Harvard Business School, and then returned as the project leader for Microsoft Works.

Gates credits Weiland with being instrumental to the company’s success. In personal journals, narrated by Zachary Quinto, Weiland confesses to not being as interested in personal computing as Gates and Allen. He approached his work as a programmer as a mode for creativity, stating, “Computers are the art form I relate to.” In an interview with Gates, he says that Allen and himself were more self-centered about their work, determined to prove they were the best. Weiland, on the other hand, “didn’t have anything to prove.”

By 1988, at the age of 35, Weiland retired, having amassed an enormous amount of wealth through Microsoft stock. At a loss with what to do with so much time and money, he developed a second career as a philanthropist.

Those closest to him describe Weiland as quiet and hard to read, yet he didn’t hide his identity from those in his professional or private life. Coming out to Gates, Allen, and Evans at the age of 17, being gay while working at Microsoft never posed any issues for him.

However, he recognized that many people in the LGBTQ community did not have the same experience, nor were they afforded the same opportunities. Thus, one of his biggest accomplishments as an activist was delivering a speech at a General Electric shareholders meeting, urging them to put an end to discriminatory hiring policies. His work with The Pride Foundation has attributed him as being an architect of the shareholder strategy to change corporate policy.

Weiland began his advocacy and philanthropy work in the midst of the AIDS pandemic, which had a profound impact on his life. He buried many of his friends through the ’80s and ’90s, and tested positive for HIV himself.

The film uses a montage of archival footage, mostly news clips, to illustrate the socio-political climate during the AIDS crises and the barrage of misinformation contaminating the airwaves about the virus and the LGBTQ community. The film’s structure hints at the juxtaposition between the beginning of the information age with the mass production and dissemination of misinformation.

Dr. Hans Peter Kiem has dedicated much of his career to finding a cure for HIV. Weiland invested a large sum of seed money to his research, enabling them to gather preliminary data to secure further funding from the NIH (National Institutes of Health). Over the course of his life, Weiland donated more than $20 million to over 60 organizations.

Despite being a champion for human rights, Weiland felt disconnected from others. He perceived his wealth as a barrier in making personal connections. He expressed being unfulfilled in his social life and often attributed it to an inherent fault in himself. “Maybe I am not finding these kinds of relationships because I am not the person I’m meant to be,” he pondered in his journal.

His ex-boyfriend Ben Sharpe recalls upsetting Weiland when Sharpe would tell him he loved him, “I really did love him, but I think he felt like he didn’t deserve it.” Suffering from chronic depression for many years, Weiland took his own life in 2006.

Bear’s film serves as more of a eulogy than a biopic, relying heavily on interviews with Weiland’s close friends, colleagues, and romantic partners to secure his legacy. Sharpe says he worries that people will just remember Weiland as a very rich man without knowing who he really was. Through the use of Weiland’s journal entries and testimony from those dearest to him, the film avoids framing a portrait of the plights of an exorbitantly rich man, to focusing on a story of human suffering and triumph.

Yes, I Am: The Ric Weiland Story screens at Toronto’s Inside Out LGBTQ Film Festival from May 27 to June 6.