To be on the road is freedom: a long stretch of highway unfolding into a future horizon of unknown spaces and chance encounters. There’s a reason road films remain a well-worn trope in cinema. Think of award winners like Nomadland (2020), Paris, Texas (1984), Thelma and Louise (1991), and classics like Wild Strawberries (1957) and Easy Rider (1969). But far fewer documentaries rely on this device, and even fewer are directed by women. It’s a gamble to get into a car with only a faint idea of where you’re going while just hoping for the best. It’s also actively discouraged if you’re hoping to get any sort of funding from a broadcaster or funding body.

The freedom to roam and explore, with plenty of room for stumbling, was not always a privilege that women were granted. “Power and patriarchy can’t afford women the possibility of quest, because within these structures women are valued as agents of social preservation and not agents of social change,” says writer Vanessa Vaselka in her 2012 essay about women hitchhikers for American Reader. “You can go on a quest to save your father, dress like a man and get discovered upon injury, get martyred and raped, but God forbid you go out the door just to see what’s out there.”

Road stories have long been the domain of men, and yet women’s curiosity and instincts have propelled a specific type of road documentary that generally avoids frontier and imperialist motifs and focuses more on liminal spaces and less visible aspects of travel such as memory and time. It’s telling that the vast majority of women-led road documentaries have been produced in just the last 30 years, when considering the road-trip film has been around since the 1930s.

Perhaps the most widely known road documentary from a woman director is Faces Places (2017) by Agnès Varda with street artist JR. The idea of the quest is portrayed at its most playful here with Varda and JR travelling across France taking photographs of everyday people and wheatpasting large-scale images—sometimes several stories tall—onto the sides of buildings. Factory workers, miners, service people, farmers, and even animals are memorialized. In one small town, a brother and sister’s ancestors are printed large and pasted onto the side of a building. In another village, one of the oldest residents of a now-quiet mining town is emblazoned on the outside of her house. “JR is fulfilling my greatest desire, to meet new faces and photograph them so they don’t fall down the holes in my memory,” said Varda while making the film. Faces Places is relatively conventional in its telling, but Varda’s charm, particularly when paired with JR’s stunning mural work, celebrates the stories of ordinary people. “What I liked was meeting amazing people by chance…chance has always been my best assistant”—a telling admission by the legendary French director.

In L.A. Tea Time (2019), Montreal filmmaker Sophie Bédard Marcotte sets out on a quest to meet one of her filmmaking icons, Miranda July. She summons the best parts of the buddy road film when choosing to bring along her good friend Isabelle, who also doubles as cinematographer. In Marcotte’s goal to reach the elusive July, she inadvertently makes a road film inspired by her other cinematic heroine, Chantal Akerman. Finding herself lost in the Arizona desert and still no closer to connecting with July, she encounters the spirit of Akerman in a pink cloud hovering above her head. The French feminist pioneer of structuralist cinema speaks to her from above: “When I make a documentary I have an idea for a subject, but I don’t know where it will lead me. I go in without an idea and I think that’s my greatest strength. I try to be a sponge and take in what I see. But all the while I try to be, how should I put it, a sort of floating listener or observer.” This spirit of discovery is what urges Marcotte and her friend Isabelle forward in a clever documentary, which is much more about exploration, female friendship, and the desire for self-knowledge than meeting a famous director or surveying the American West.

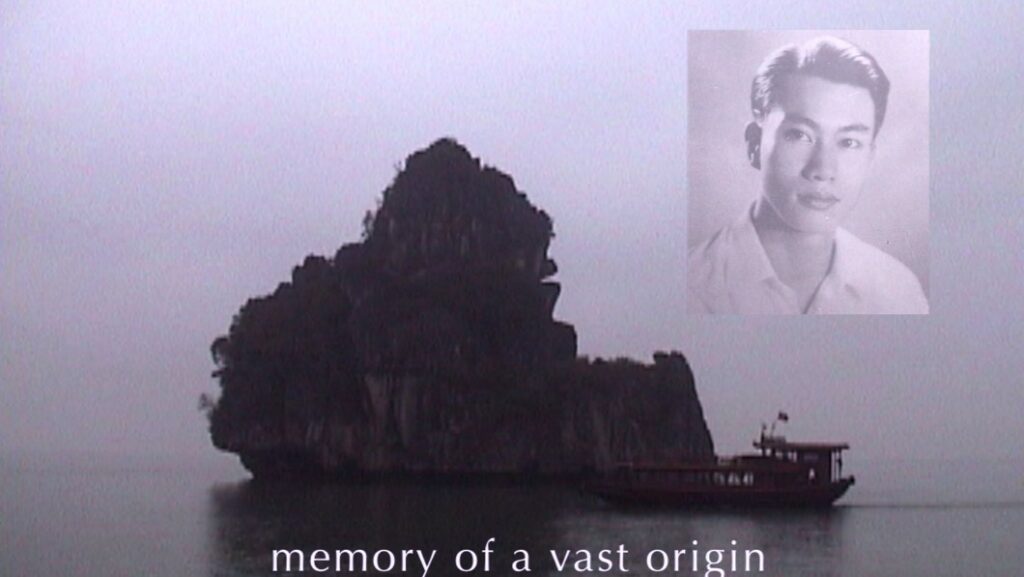

Trinh T. Minh-ha takes an opposing approach to the road documentary in her 2016 film Forgetting Vietnam. In it, the Vietnamese-American director and theorist travels home rather than abroad, gathering footage she shot during trips to Vietnam between 1995 and 2012. Her film is an ode to the landscapes, mythology, songs, and women of Vietnam while also marking the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. It’s a travelogue of an emigrant who left as a teenager capturing the “scent and sound of memory” of a place that is at once familiar and foreign.

Historically, so much of the storytelling about voyaging and travel has been about conquering nature and people. In Forgetting Vietnam, Trinh highlights the tension between traditional folklore that centres on the land and its citizens with present-day Vietnam and its long-reaching shadows of colonialism and war. She overlays shots of women working onto footage of Vietnam’s countryside taken from a train. “Her land. Her country. Scorched. Mined. Bled red.”

Trinh’s film tells a different kind of travel story: one that is anti-imperialist and experimental, offering numerous avenues of interpretation to the viewer. The filmmaker points her camera to the land, the waterways, and the liminal spaces that bind these regions together. She is particularly interested in filming boats in water. In an interview for Frieze in 2018, she states, “It’s not the person in the boat—neither the boater nor the boat passenger—but actually the boat itself and the sea. It’s a way of shifting our attention to the fact that we are not the centre of the world.”

Courtney Stephen’s poignant essay documentary Terra Femme (2021) is specifically about how women portray the world around them. Stumbling across a treasure trove of amateur travel footage taken by women between the 1920s and 1950s, Stephens teases out the idea of discovery, representation, and the female gaze. “What does the narrative of exploration offer women?” Stephens asks in her documentary originally conceived as a live narrated performance. The “female gaze” is never purely neutral and Stephens lights upon this point by offering both the wonder and the limitations of footage that has been resurrected nearly a century later.

Terra Femme features films from Kate Tode and her husband Arthur, who each owned a camera and travelled the world filming ancient Greek ruins, volcanoes and kangaroos. Like collectors, they brought back footage that they shared with friends and at amateur cine-clubs. Arthur’s films often spotlighted Kate in front of famous landmarks, whereas Kate’s footage rarely featured Arthur. Meanwhile, Armeta Hearst was a Black American who travelled North America by car, rail, and air during segregation. She took trips with her husband, who was a porter for a train company, and they would take turns filming. Her footage is personal and is taken inside homes, at family gatherings and in shopping districts. Hearst’s films could easily be interpreted as home movies as opposed to travelogue footage, and yet what she was capturing in terms of mobility for a Black woman at that time was extraordinary. “Travel carries with it the promise of transformation, and so does digging in archives,” says Stephens in the film. “There is that hope by some feminist act of retrieval that a nobody becomes a somebody.”

The beauty and uniqueness of these early amateur filmmakers’ work coupled with Stephen’s narration and moving soundscape is hypnotizing. One could point to these women as trailblazers for what they had accomplished so early in the 20th century, but it is undeniable that their ability to film in far-flung places was a result of them being resourced enough to travel and afford a camera. Adelaide Pearson, a wealthy American who travelled throughout Asia, was motivated to bring back stories of her trips to her hometown in Massachusetts. She filmed a Berber tribe and captured the first-known colour footage of Mahatma Gandhi. There was an early tourism circuit in which the well-heeled travelled to colonized lands like India and the Philippines hoping to get a glimpse of “antiquities” before they disappeared. Midway through the film Stephens aptly asks, “Do modes of objectification and exoticism differ in women’s films than in those of Western men?”

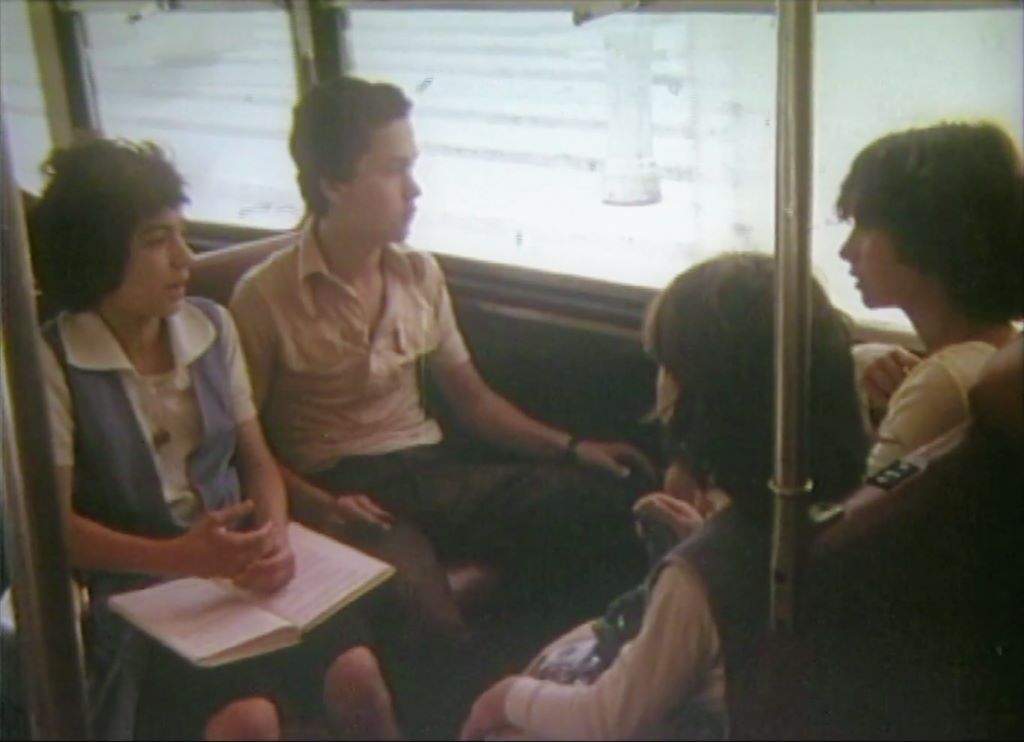

In Trinh T. Minh-ha’s first film, Reassemblage (1982), which she filmed in Senegal, she says “I do not intend to speak about; just speak nearby,” in an acknowledgment of the gap of objectivity that exists between the director and the people she’s filming. It’s a slogan that Chantal Akerman seemed to live by in her own documentary work. In her 1993 film From the East, Akerman set out on the road to Russia, Poland, and the Baltics following the collapse of the Soviet Union to record life in these countries before it drastically changed. Her film is an impressionistic snapshot of that time, of the differences between capitalist western cultures and a crumbling Soviet regime where waiting for things is a part of daily life. In From the East, people are waiting in line for everything: for the bus, the train, and to buy food. The viewer is often not really sure what people are waiting for, as Akerman focuses on the act itself rather than the result. She perches the camera inside of trains and cars, dollying slowly, cataloguing the faces of people who register expressions of indifference, curiosity, and weariness. Much like Akerman’s other work, the film is about repetition and the poetry of the everyday. As Jonathan Crary writes in his book 24/7, one of Akerman’s achievements is to “show the act of waiting as something essential to the experience of being together, to the tentative possibility of community. It is a time in which encounters can occur. Mixed in with the annoyances and frustrations is the humble and artless dignity of waiting.” What Akerman was capturing was something that is so much rarer and fleeting in the 21st century: the presence of time.

1978’s Letter from Beirut is as much a travel film as it is reportage. Director Jocelyne Saab returns to her home country of Lebanon three years after the start of the civil war during a lull in the country’s fighting. “I’m in my own country like a traveller who has taken a moving bus,” she says. Her city has been transformed by war, and ghosts linger at every corner. She wanders her divided city, meeting with people in cafés, on transit, in jail, and at United Nations army bases. The economy has been decimated and many of the people Saab interviews are struggling to survive financially and emotionally, tormented by what is known as, “the events” to locals. “In Letter from Beirut, I wanted to show how abnormal things become normal,” she is quoted saying at the Courtisane Film Festival. “I believe that, very often, the gestures of everyday life have more weight than political declarations.”

Visiting landmarks from her past, Saab documents how quickly a city and its people can change. A museum became the demarcation line separating East and West Beirut where snipers would post up along the “crossroads of death.” She documents the street corner where the civil war was sparked, and where a statue of the Virgin Mary now stands, arms stretched wide.

She reminisces about a time when a past Lebanon conveyed feelings of la dolce vita. It’s hard to not see some parallels between Saab’s chronicle of her home country and that of Trinh. Even though Saab points out that she’s “happy to move around and rediscover what is still familiar in her country,” there is nonetheless a palpable grieving. At the end of the film, we see Saab on a Ferris wheel overlooking her native city. “Beirut is aimlessly turning. Time is blind. My country is bleeding and burning.”

The road film, as it is conceived by women, takes many forms, documenting what is visible and what is no longer there. These directors focus largely on what is unseen: memory, ancestry, time, alienation, women’s work, and the banality and beauty of everyday occurrences. In these travel stories, regular people are both elevated and celebrated.

There is a keen sense of wonderment and awe throughout all of these films, whether it’s embracing chance, witnessing historical events or re-discovering one’s homeland (with the mixed emotions that brings). And yet women’s travel films aren’t immune from straying into territories of imperialism and exoticism. The female gaze in documentary is as influenced by class and privilege as in any art-making discipline. Road films made by women convey a specific idea of voyaging and adventure, whether that’s a new take on the buddy film or a more observational look at the political. The lens through which travel is viewed casts light on both the quotidian and the profound, and women are uniquely placed to capture the diversity of these expressions.