We typically don’t know or think much about the engagement of the Inuit in the broader world, nor the impact of the broader world on the Arctic. How many Canadians realised that the voice of Inuit was barely heard in the fight against the seal hunt back in the 1980s?

Advocacy on behalf of baby seals back then was remarkably successful, especially after the hunt attracted the attention of celebrity animal rights activists such as Brigitte Bardot. No attention was paid to the traditional methods employed by the Inuit in their hunts. The campaign specifically targeted the hunting of baby harp seals with clubs, although indigenous people typically hunt with harpoon and gun. The east-coast hunt harvests thousands of seals in a short period of time, while indigenous hunters hunt all year round, often bringing home one or two seals from a week’s efforts to feed the entire community. But who can tell the difference between a harp seal fur and that of any other seal? Who can tell who did the harvesting, or what method was used?

The anti-fur movement picked up momentum in the 1970s and into the 1980s. The excellent documentary How To Change The World (2015) tells the story of the origins of Greenpeace and shows how the founders diverged over the fight to end the seal hunt. Bob Hunter saw it as a local issue: he recognised that hunters in Newfoundland and elsewhere depended on seal for their livelihood. Paul Watson saw something else, and pursued the hunters with fierce passion. He and others found that pictures of the seal hunt—the baby seals with drops in their eyes, the carcasses stripped of their white fur and left on the ice, the blood—were effective fundraising and advocacy tools.

When the Council of Ministers of the European Economic Community (EEC) adopted a directive in 1983 banning the import of harp seal pup skins, it had a devastating impact on indigenous hunters, including those in Greenland. Almost immediately, all seal pelts became practically worthless, the cost of hunting far exceeding the prices being paid for seal skins.

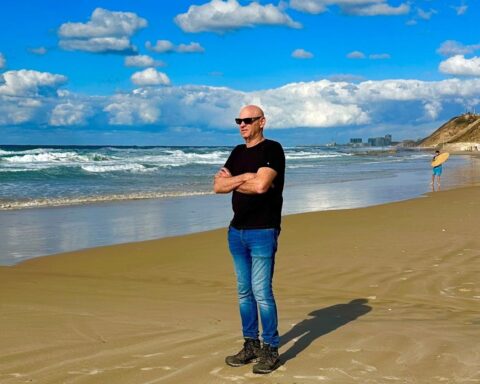

More than three decades passed before an Inuk was able to make a feature film that showed a native perspective on the seal hunt. Alethea Arnaquq-Baril’s documentary Angry Inuk is that long-awaited film. (Read the POV review of Angry Inuk here.) It premiered at Hot Docs 2016 to critical cheers while winning the Vimeo On Demand Audience Award and the $25,000 Canadian Documentary Promotion Award. In the developed West, where people have long taken as given that seal hunting is a bad thing that should be stopped, that’s quite an achievement. The enthusiastic response to Angry Inuk was owed in part to its charismatic main character, Aaju Peter—charming, educated, articulate and determined—and in part to Arnaquq-Baril and her own commitment to her people.

Aaju Peter has been angry since she was forced to give up her language and culture as a teenager, but the main subject of her ire is the misled delegates to the European Union (EU) Parliament. She has worked tirelessly to advocate on behalf of the seal hunt, demanding that the EU overturn its ban on the importation of seal fur. The wording of the ban makes it sound as if indigenous seal hunting is fine, as long as the meat and fur are used for local purposes. But, Peter argues, the arctic seal hunt is and has always been commercial: hunters need to sell or trade the furs in order to buy fuel and ammunition, not to mention pay the rent and buy other goods that they and their families cannot produce themselves. The ban has eliminated the market for their wares, and has left the men in the community without purpose and without the ability to provide for their families. In an interview with This Magazine in 2010, Peter described the likely impact of the ban, and the attitude of the people who imposed it.

“The exemption is very restrictive and absolutely useless. I won’t be able to sell my clothes in Europe. If [the seal] is traditionally hunted and is used for cultural trading purposes only, then it’s okay They want us to be like little stick Eskimos who are stuck on the land and go out in our little Eskimo clothes with a harpoon. They will not let us hunt with rifles and snow machines. They will not let us sell commercial products. It’s a form of cultural colonisation. A journalist in the Netherlands called it the Bambification of the Inuit, like we’re in some Disney movie.”

Angry Inuk opens with a scene of the spectacular Arctic landscape in springtime. We see a man and his grandson at the edge of the ice as they wait patiently for a seal to surface. The man raises his rifle and shoots, then the two paddle out to the seal. The carcass is brought into the boat. Back on the ice, the animal is butchered. Parts are consumed immediately. The skin is handled carefully, cleaned in the icy water then transported, along with the meat, back to the community. Back home, the meat is shared among family and neighbours. Every part, including those that we might recoil at, such as brains and intestines, is valued. We then see the efforts of women to prepare the seal skin: scraping and softening it to make it ready for use in clothing and accessories.

The depth of observation and precise attention to detail evidenced in Angry Inuk’s first scenes is followed throughout this intimate film. Alethea Arnaquq-Baril has made a deeply personal and well-researched documentary intended to educate the world about the Inuit commercial seal hunt and the destruction that the ban has caused to the Inuit people, and to influence the decision-makers in the European Union and elsewhere.

“My film is an attempt to get at some of the root causes of the situation that our society is in,” she told POV in an interview prior to the film’s completion. “Our young men in particular are struggling, and have poorer outcomes compared to the rest of the country and even compared to Inuit women. The seal skin industry has played a huge role in transitioning from our former lives, pre-contact, into a global economy. It allowed our men to make that transition smoothly, to allow them to feel that they still had a purpose and could provide for their family. That was taken away. The impact that had is deep. It’s still happening.”

One of Arnaquq-Baril’s insights during a long period of research was that there are animal welfare or rights organisations that have taken on the seal hunt as a crusade. They have used graphic imagery and creative marketing techniques to make the seal hunt one of the most reviled activities on the planet. They have also used the seal hunt to raise millions of dollars. The organisations use those funds for valid purposes, such as the protection of endangered species, but Arnaquq-Baril challenges the use of seals and the seal hunt in their efforts.

As part of her research, Arnaquq-Baril filmed her efforts to contact representatives of animal welfare advocacy organisations. The results are fascinating: advocates against seal hunting appear to refuse to talk to Inuit, and Inuit claim never to have seen an animal rights activist in their communities. Arnaquq-Baril also discovered a revelatory CBC radio piece. In 1978, on As It Happens, Barbara Frum interviewed Sea Shepherd founder Paul Watson, who was in a candid mood. Watson denounced those who would use images of apparently crying baby seal to raise funds, when it was well-known that seal were not endangered—and the tears were a natural feature to keep the seal’s eyes from freezing.

Documentaries can be presented neutrally and objectively, without a narrator taking the audience through the story. That isn’t the case with Angry Inuk. When Arnaquq-Baril became enmeshed in the action of the doc, she needed to acknowledge that she had a hand in the events depicted on screen. Daniel Cross from Eye Steel Film, one of the film’s main producers, pushed Arnaquq-Baril to narrate and become one of the doc’s principal characters. Initially, she resisted—until it became clear that the new voice pushing for change and driving the film was her own.

Speaking of Cross, Arnaquq-Baril says, “It takes a good producer to pull the story out of you without shaping it themselves.” She and Cross got the film into shape with a treatment and trailer, and they were both pleased when the NFB came on as a co-producers. At one point, Arnaquq-Baril was ready to go into production, but Bonnie Thompson, her NFB producer, told her to shoot more. Both production companies pushed her to react to reality and not to assume that she knew everything from the Inuit perspective. She was also advised not to take the perspective of her audience for granted, to show them what hunting looks like and to tell the stories of hardship.

And so we see Aaju Peter not only with her law degree heading to Brussels to advocate, but also her in her kitchen, sewing seal skin into clothing and accessories. We see the appreciation of people in a community when they receive fresh meat. We hear the hunter talk about what he normally eats. “I was offered vegetables once, but I didn’t like them.” We also see what it costs to buy everyday items in a local store.

Some of the most compelling footage is actually of Arnaquq-Baril herself, as she conducts her research online. She finds out who the main anti-seal hunt advocates are and sends e-mails. She manages to speak on Skype with a former activist, who acknowledges the importance of the seal hunt in fundraising and actually apologizes for the harm she and her former employer have caused to the Inuit. One of the themes in the film is the Inuit’s unique perspective on anger and advocacy, which has helped them to survive in a harsh environment but has not situated them well to defend their position in the world. Inuit culture traditionally deals with anger via face-to-face confrontation, resolving it on the spot. It’s calmer, more humorous than anger in the ‘south.’

Aaju Peter, and now Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, have learned how to operate in the legalistic space of governments and the European Union, and they are also learning how to use their style of humour to confront people who have much more money than they do. Wearing their traditional garb to Brussels, they were confronted by an enormous inflated seal and people handing out white seal dolls (presumably of fake fur) to all of the politicians. Their traditional clothing only served to reinforce their marginal position.

In Canada, they hear about an anti-seal hunt protest and decide to take a group of Inuit students down to Toronto to stage a counterprotest. Outside of the Eaton Centre in downtown Toronto, no anti-seal hunt protesters arrive, so the students drum and walk in a circle, promoting the benefits of eating seal. Another intervention: after anti-seal hunt advocate Ellen DeGeneres took a famous selfie at the Oscars, Inuit responded with pictures of themselves dressed in their finest sealskin clothes and tagged them #sealfies.

Angry Inuk is as much about the evolution of Inuit activism—what Peter, Arnaquq-Baril and others have learned, what they have tried, who they have tried to influence—as it is about the seal hunt and what it means to the community.

The response to the film by young audiences at Hot Docs was overwhelmingly positive. Arnaquq-Baril told POV, “We showed the film to an afternoon screening of high school students. At first, they were grossed out by the seal hunt, but by the end they were cheering us.” When Peter appeared on stage after screenings or in the lobby afterward, she was treated like a rock star.

There were at least two advocates on behalf of animal welfare in the first adult audience; POV had the opportunity to speak with them later. One felt that the type of protest shown being conducted by Inuit in the film was just as confrontational as Sea Shepherd-style protests. She felt that the film vilified animal rights groups, and questioned whether Arnaquq-Baril really did want to talk to such people or just confront them.

One of the representatives of an animal rights group, Sheryl Fink of the International Federation for Animal Welfare (IFAW), was surprised to find herself in the film. Fink attended the Hot Docs screening because she had been invited by the CBC to participate in debate with the filmmaker after the screening. She felt that there were misrepresentations in the film, but that it was “important to understand the unique perspective, even if [she] disagrees with the facts.” She agrees with Arnaquq-Baril that the language used to describe the east coast seal hunt has created unintended problems for the Inuit, but says it is the language that the Government of Canada uses. Fink and the International Federation for Animal Welfare are open to continuing the dialogue now that it has been opened.

Arnaquq-Baril is clear that the animal rights community shares objectives with Inuit. Her film and activism are about broader issues than just seal hunting. “I wanted to draw attention to the fact that it is almost entirely our hunters that are the ones battling the uranium mine in the caribou calving grounds and the massive iron mine that is going to have shipping routes through narwhal calving grounds. Seismic testing that the Canadian government wants to do—it’s Inuit hunters that are fighting that fight. Bowhead whale hunters lobbied for a bowhead whale sanctuary. These are Inuit examples but that’s the truth around the world. There are indigenous examples around the world which show that people who live on the land and work directly with wild animals are the ones that are the planet’s guardians. Animal rights groups have attacked people who hunt wildlife. My argument is that those are the very people defending the whole ecosystem, not just the specific animals that they hunt. These animal rights groups and environmental groups have actually pushed us toward massive destructive resource extraction industries faster than we want to approach them.”

After the screenings at Hot Docs, the conversation has started to shift in favour of the Inuit. Will the Government of Canada withstand renewed lobbying from Pamela Anderson? Will the European Union overturn its own ban? A compelling feature documentary, Angry Inuk is the best lobbying tool the Inuit have produced to represent them in the debate. Most importantly, the shame in being Inuit is turning to pride.

Angry Inuk (Clip) from NFB/marketing on Vimeo.