For many viewers, W. Kamau Bell is the stand-up comedian and CNN contributor who has taken his stage shtick and used it to ask difficult questions to his fellow Americans. His United Shades of America is both entertaining and insightful. It shows an old-school way of engaging in discourse even in cases that might bring radical disagreement.

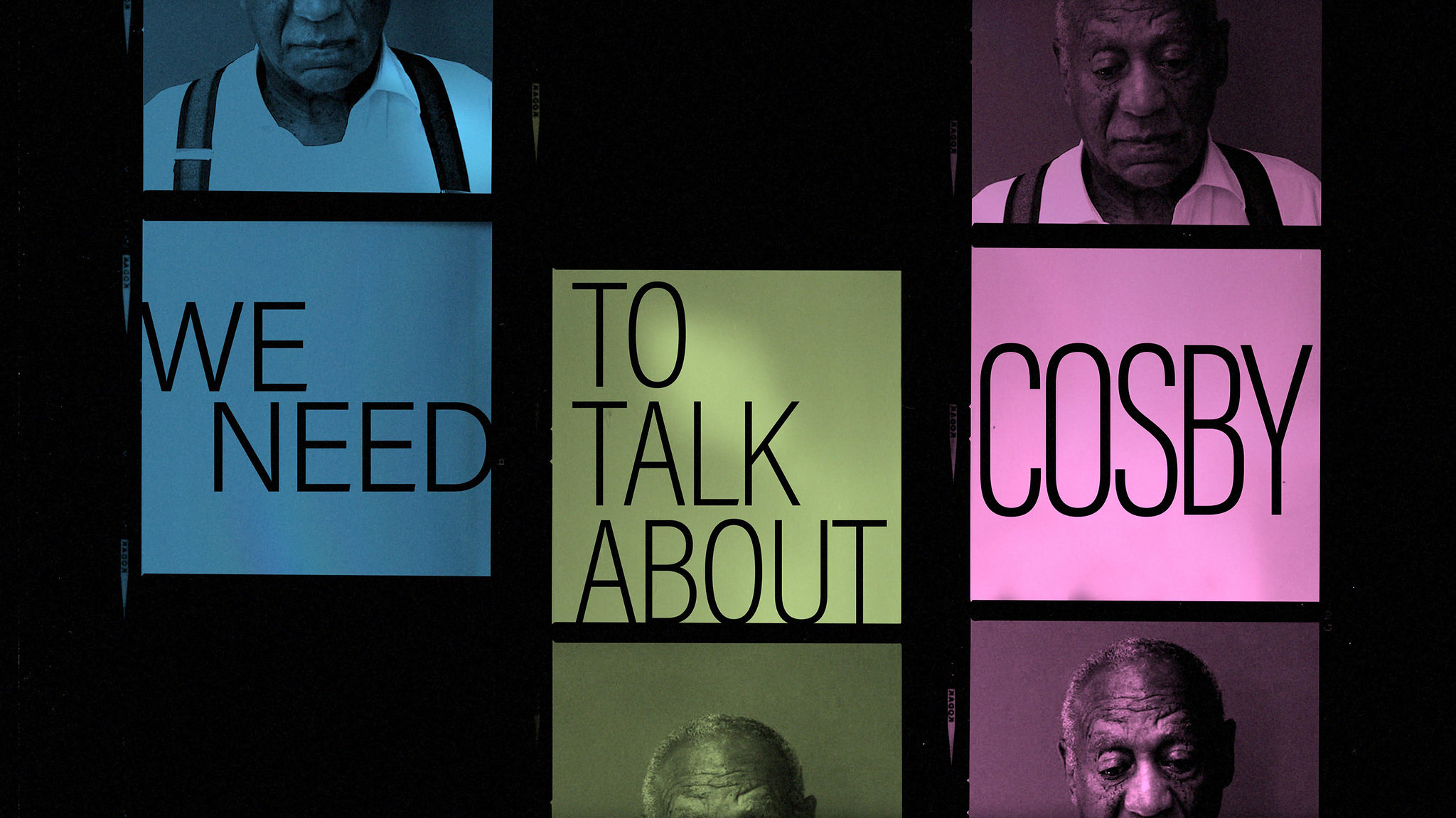

With We Need to Talk about Cosby, his four-part Showtime series having its world premiere in full at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, Bell and his team tackle the immensely complicated legacy of the pioneering African-American comedian whose story is now inexorably linked to allegations of severe sexual crimes committed over decades.

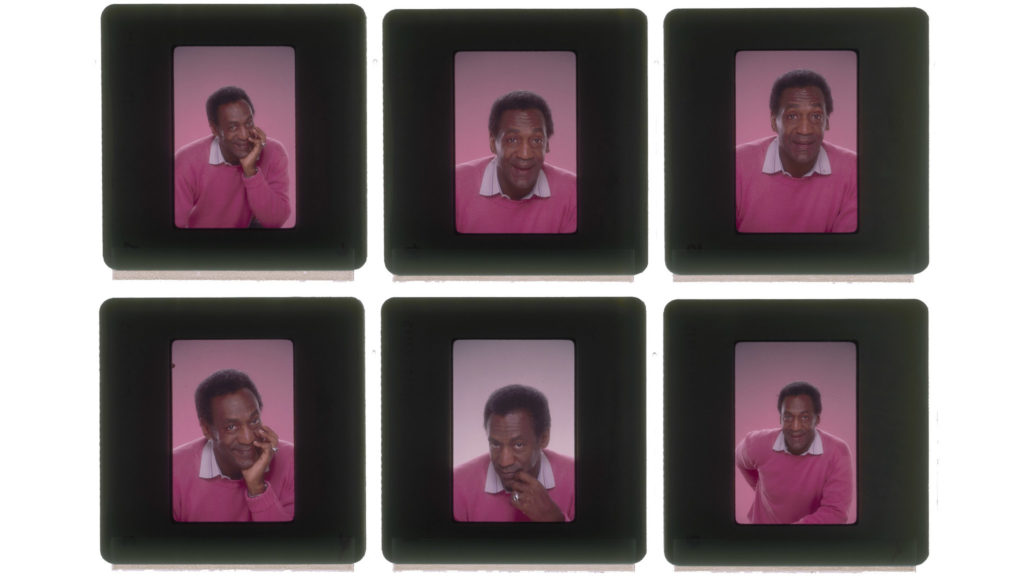

Like Bell, I’m part of the “Cosby” generation, and the film does an exemplary job of situating that period through the 1970s and 1980s where the near ubiquity of a very different kind of Black figure emerged thanks in large part to Bill Cosby’s charismatic talent. We learn in detail about what was alleged to be transpiring through this same era, complicated further the circumstance while constantly refusing to succumb to simple reductions that might easily let one navigate conflicting elements.

In a culture where it’s often much easier to sweep any sense of nuance away in favour of simplistic narratives or to simply erase the complexity of the situation, Kamau’s documentary does a remarkable job of allowing all the conflicting elements to be examined. The result is a rich and rewarding full conversation that makes sense in a grander scope not only the specific of one man and the women who have come forward, but also the larger discussions about race in America, the nature of the criminal justice system, the real challenges for women coming forward to tell their stories and be believed, and how these things all interact within the nexus of one individual.

We spoke to Bell over Zoom prior to the We Need to Talk about Cosby’s debut at Sundance.

POV: Jason Gorber

WKB: W. Kamau Bell

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: Congratulations on the documentary. I wish we were meeting in person!

WKB: I know. Everybody keeps saying have fun at Sundance. I’m, like, “at Sundance…” [laughs]. I’m in the same Twitter/Zoom seat I’m always in!

POV: Let’s start with the title. Do we need to talk about Cosby?

WKB: That’s actually one of the great things about the title. If you don’t think we do, then go watch Yellowjackets or other Showtime projects. But I think for a lot of people, we do feel we do need to talk about Cosby. When we started, he was in prison. I can’t remember a time in my life when Bill Cosby wasn’t a part of my life. Now that this man is in prison, at the time for what we thought was maybe the rest of his life, there’s gotta be something we can learn from this story.

POV: Obviously, Cosby had such an incredible legacy of pedagogy. If there’s one thing that we’re actually going to learn from him, using the very tools he taught our generation, your documentary takes his inspiration and applies it to his own behaviour and legacy.

WKB: Yes. It’s such a Gordian knot. But as I worked on this, I realized, wait a minute, Bill, you taught me how to make this documentary. You taught me that I should be good and moral, and support my community, and uplift others and try to be a good person. Not be a perfect person, but try to be a better person. I try to do the thing I’ve seen him say to do: not to just be good on stage, but to try to do some good off stage. This [documentary] is a part of his legacy.

POV: When did you find yourself questioning his role on your contribution to the art form – as a communicator on television, or as a standup comedian? Cancelling is easy. You just ignore something, as there’s nothing easier than canceling something that you don’t care about. The worst thing is boycotting something that you genuinely feel a loss over boycotting.

WKB: It started way before there was even some sense that somebody would allow me to direct a four-episode docuseries about him, first of all. For me, this began when media started to care about me or my career or thought I was worthy of interviewing. They would ask that question, “Who were your favourite comedians growing up?” Internally I’d be like, “Shit, how do I answer this question?” This was at the time the allegations were out. If I just say Eddie Murphy, and then I try to fill in the rest, it sounds weird. But if I say Bill Cosby, it sounds like I’m ignoring the assaults and I’m ignoring the things that we’re starting to hear. At the time, and I wrote about this in Time magazine, I would say “the artist formally known as Bill Cosby” as a way to go, “You know what I mean, and you know why this is a difficult thing to talk about.” The journalists would go “oh,” or they would laugh and we would move on. But to me, that was the beginning of admitting that I can’t disentangle the good stuff this man did, which I can feel coursing through my veins, from what I now know and believe.

POV: We just lost Mr. Poitier, an icon. Inevitably, his career is directly connected with Cosby. There’s been all kinds of navigation around that, and I thought of your film explicitly that was taking place. Have you received, even before this film came out, backlash from people who find it easier not to do the work?

WKB: Yeah, if you go to my Instagram or my Twitter right now… [laughs] I’m sort of at this point where I don’t scroll that far down because that’s where you seem to find it.

POV: You responded to me, so I seem friendly, I guess.

WKB: I have all of the checks and balances on it. So if you’re a verified person, I can see it, or if you’re a person who has genuinely interacted with me I can see it, but I’m not putting up a tweet and then scrolling down to the bottom of all of the responses anymore. And the same on Instagram. If you click one level deep, it stays pretty good, and then further, I’m not. But I’ve seen enough to see people say things who haven’t seen it.

Ultimately, the people who are going to hate this film the most are the ones who are never going to watch it. If you watch it, you have to appreciate that there’s some level of discussion or artistry in the film. It doesn’t mean you have to love it, but you’ll appreciate the fact that there’s legit work in it. I’ve already had people say things like, “Hollywood’s going to make a documentary about Bill Cosby, but won’t make a documentary about Harvey Weinstein or Woody Allen or Jeffrey Epstein.” I’m like, first of all, those docs exist. Roger Ailes, and Larry Nasser, we have docs about white men who do bad things, who are sexual assaulters and rapists. For me personally, I didn’t grow up idolizing any of those people. I don’t have the same level of conflict around those people. I can easily go “those people are wrong” and throw them away in a way that is more difficult for me with Bill Cosby.

POV: I don’t want to dive too much into offset, but what’s interesting is that you just equated Epstein (convicted), Weinstein (convicted), and Woody Allen (charges legally dropped). Are your perspectives on that particular story shaped by assumptions that are not backed up by criminal justice system? Whatever the assumptions we have about Bill Cosby, they’re at one point in time backed up by his own witness testimony that he did these things, and that there was a very specific technicality that resulted in his release. How do you navigate all of that? How do you decide what’s true? How do we decide who to listen to and who to abide by, and who to paint with a brush saying that this person’s terrible?

WKB: So, for me, the idea is that as a culture, when people attempt to gaslight me about Bill Cosby, they bring up these people. I’m not bringing up these people. If you’re going to bring up Woody Allen, there’s a doc about it that you can go watch to make your decision. [There are several.] That’s my point to that. Even with the Bill Cosby case, the one case that was really adjudicated was Andrea Constand. The cases of more than 60 women were not adjudicated. Some of them were witnesses in that case, but there are no convictions for those women, and a lot of them were outside of the statute of limitations as we talk about in the film. At some point, you can’t say the legal system said this, or that the legal system has said that 60 women have been raped or sexually assaulted. You have to make your own decisions. I would say, for me, having done the work I’ve done in my career, having been lovingly educated by the women in my life who’ve talked about this, also having done the research to see that rape and sexual assault is underreported specifically because survivors often don’t feel that the criminal justice system in America as a whole is not going to take them seriously. And worse, it’s not going to help them, and it’s not going to give them healing and care. It’s going to, as Lily Bernard says, blame and shame.

I take all of that in and go, “There is no reason why more than 60 women would lie about having been raped or sexually assaulted by Bill Cosby.” When I got to sit down and hear some of their stories, the ones I talked to, I believed these women because they were all credible. They don’t fit into any convenient narrative that they were trying to make it in their careers, or they were “groupiesl” which is not a word I use in my regular life. They don’t fit into whatever you want to claim them as, in for lack of a better word, “starfuckers.”

POV: The notion of taking down a Black man is part of the way sexual assault allegations have been used in your country You’re navigating all of that in a four part-documentary series that has to be engaging if not entertaining, both for people who are open to the conversation or closed off from it. How do you even pitch that?

WBK: As we said, many of the women are Black…But as far as how you pitch it, I was fortunate that Vinnie Malhotra at Showtime had been one of the execs at CNN who had said we should give this guy a chance with United Shades of America, so we had an existing business relationship. He knew what kind of work Kamau does. The thing everybody liked was that we were going to talk about all of it. We’ve seen many different styles of this documentary. For me, one of the two tentpoles of this film is Surviving R. Kelly, which was so impactful because Dream Hampton was basically saying this is an active crime scene, and we need your help catching the criminal. Then you look at O.J. Simpson, Made in America, where they tell you the story of OJ, but also the story of America, and how these things feed and support each other. For me, these things are where I was drawing inspiration from.

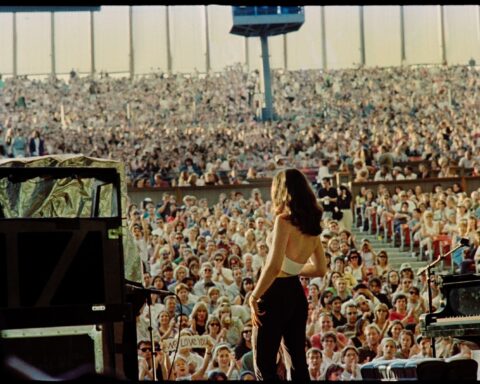

On top of that, I think because I’m a standup comedian, I’m used to standing, I’m used to having to navigate crowd dynamics. That means that when I’m making this film, I’m thinking about the people who hate, who don’t believe the survivors, the people who feel I’m not going hard enough in a portrait of Bill Cosby. As a comic, you stand on the stage, and you go, “Oh, that table at the back is a bachelorette party and they’re too drunk and they don’t care. These people in the front are my biggest fans ever. They just want to hear everything crystal clear, and they’re laughing at every joke and they’re actually so excited they’re talking to me through my set which is interrupting me. Then these people in the middle got free tickets. As a standup comic, you’re used to navigating crowd dynamics, so, as I’m making the film, I’m thinking about who’s watching it and who I want to talk to in individual moments. I’m also used to focusing on one section of the crowd because I see there’s something they need me to address. With the doc, sometimes I’m 100% talking to Black people and going, “Look, I know what some of you are thinking. I’m with you on this.”

POV: That being said, you had to change the dynamic as the narrative changed. It is much easier to tell a story after he’s dead.

WKB: Yes. Or if he’s in prison and he’s not getting out.

POV: Tell me about that moment, when you’re there shooting and you get the news on your phone.

WKB: Everything that is happening right now in the world is coloured by COVID. We were in the middle of shooting at one point, and we flew to Philadelphia and New York, the East Coast, in March of 2020. While we were there, COVID was in the news, and we were like, “Is this a real thing, is this not?” Then the NBA shut down while we were in Philly. So I remember going after that, “I’m not going to shake anybody’s hands.” That was my response. No masks, no anything, just don’t shake hands. So then we broke and thought it’ll be a delay of a couple of weeks. Then we had to shut down production of the film because we got to a point where we couldn’t get any new interviews as there was no vaccine. I have to say: “Everybody, get vaccinated!”

We did what we could with what we had and then shut down. And at that point, I thought we were done because there have been other Cosby documentaries that have shut down, other documentaries that exist that never came out. We finally started up again, and on our last day of shooting was going to be in Philadelphia. We’re there, masked up, doing all the strict protocols, and it’s already awkward to be on a set like that. I go to the bathroom after we interview Sonali, and a friend of mine, who’s a comic, texts me and says, “Your film just got more interesting.” I ran out of the bathroom expecting I’m breaking the news, meanwhile, everybody’s staring at their phones. We’re waiting for a prosecutor to show up. I was like, “Is she still coming? And they were like, “Says she is.” I’m like, “She’s not coming.” She didn’t come, which I understood.

POV: That’s interesting. I actually misread that in the film. I thought that the defense attorney who speaks to that point was the interview you were about to do, the one who says that, legally, he never should have been convicted.

WKB: No, we were supposed to talk to [prosecutor] Kristen Fedden and she didn’t end up coming. Our interviewee is not showing up and, understandably, everybody in the country is wondering what’s happening. We’re in Philly, where it feels like the most is happening. Suddenly we become, as Katie King the showrunner said, a breaking news crew. We sent cameras to the prison, sent cameras to his house—these giant RED cameras that are not good for breaking news. Our cinematographer Hans was like, “Are you coming with us to Bill Cosby’s house?” And I was like, “No.” And he was like, “Oh yeah, I forget you’re famous sometimes.” [Laughs.] That would be weird if I showed up at his house.

Then we asked if the film was over now, has it gotten too complicated? I went back to the hotel and checked in with the producers and editors, who were at home working on this, and we had a Zoom meeting with a lot of emotions because people had been staring at his face on their laptops for months now, some years. There was no agenda. We just talked through through the tears and figured out what do we do. At first, it felt like we had upset the whole apple cart, like we have to redo everything. We have to book 100 new interviews. When we looked at it we saw that, no, the work still stands. We just need to address it. Which meant, ultimately, we had to push other pieces out of episodes 1-4 because this became a key moment that we had to address.

POV: As a standup comedian, you tell truths through fictive stories. You get on stage and you tell fictive stories, but you have a responsibility as a documentarian now to tell truths and navigate all of this.

WKB: This is how I feel about United Shades, wanting to have opinions that are backed up by journalistic fact. We talked about this with Vinnie at Showtime as we were trying to figure out the format early on. He said “Kamau, this is really an op-ed from you, so we need to cross all of the t’s and dot all of the i’s and make sure that the things you are saying are legally the truth. We need to see between truth and opinion but it’s an op-ed.” It’s in the newspaper, but it it’s in the editorial section of the newspaper.

We only have four hours, which seems like a long period. But this man has a 50-year career, and what I believe and what we’ve heard is that women have accused him of sexual assault consistently throughout his career. We cannot cover everything, but the great thing about archival is that we can show things instead of going, “This is a part of this conversation too.” The conversation doesn’t end when the film ends. Rhat’s when you turn to the person next to you and go, “We need to talk about Bill Cosby.”

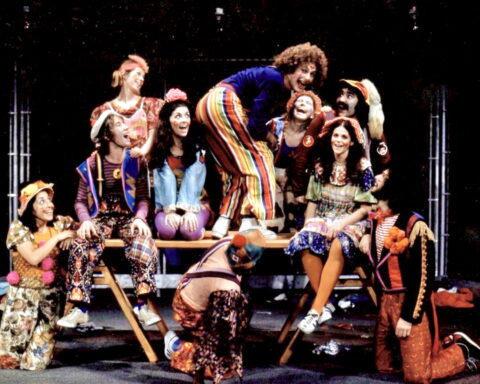

POV: When you’re showing some Different World stuff, Tupac shows up as an actor, and he has a complicated legacy that many fans choose to ignore or dismiss. Can you talk about navigating some of these other stories that are not actually discussed, as well as the notion of witnessing? You have made an editorial decision to include an image of Woody Allen when you look at Bill Cosby as an early performer, which is going to have a certain reaction now. Tupac does not have that reaction for many in the community.

WKB: And Woody Allen does not have that reaction for many in the community, too. When we first put this together, I and the other producers sat around and gave an assignment to everybody to write a paragraph about their connection to Bill Cosby. We quickly found that everybody’s connection, as far as how they took the information in—what they thought about it, what was important about it—was different. In using these archival pieces with Tupac and Woody Allen, which mean a lot to different people, you’re saying here are more conversations that we need to have in this bigger conversation.