The 2023 Sundance Film Festival began with a splash of controversy when the dramatic jury, including deaf actress Marlee Matlin, walked out of a screening because the festival didn’t provide proper captioning for them to enjoy and assess the film. Ironically, though, the Sundance selection The Tuba Thieves, screening in the NEXT programme, features a brilliant interplay with captioning, sound, and silence. Directed by Alison O’Daniel, The Tuba Thieves is an immersive sensory experience unlike anything audiences have encountered before.

The film is an uncategorizable work that draws upon elements of documentary, narrative filmmaking, essay films, and city symphony movies to explore the peculiar story of a string a tuba thefts in Los Angeles in which instruments were pilfered from high school music rooms. However, audiences hoping to learn about the thefts themselves might best head to Wikipedia since O’Daniel, who identifies as d/Deaf/Hard of Hearing, isn’t really telling that story. Instead, The Tuba Thieves invites audiences to experience the loss of sound and the role that music plays in daily life, whether it comes in the form of a big brass band, in the whir of city traffic, or the slight rustling of leaves that connects one to nature.

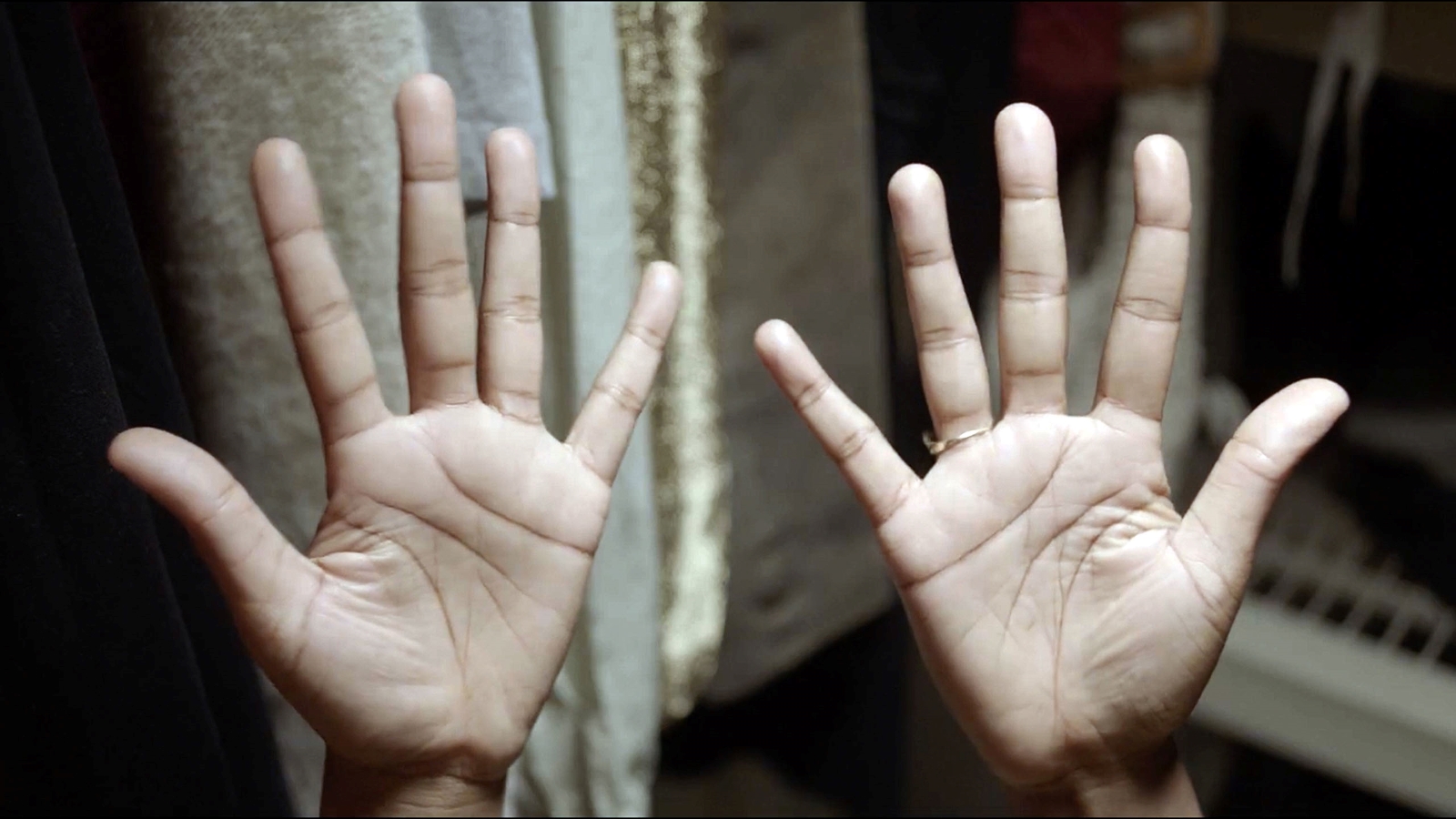

While The Tuba Thieves features a cast of real life figures who crossed paths with the heist story, it includes several deaf actors in vignettes that are loosely structured around Los Angeles events of the time and the loss of sound more broadly. The star of the film, however, is the immersive sound design that O’Daniel creates to make viewers active participants in the film. The sound levels mix dexterously according to the drama—pauses punctuate the audio and The Tuba Thieves asks audiences to imagine the sound or to consider experiencing these day-to-day events through the ears of someone who is deaf or hard of hearing. The captions add another level of engagement to the film as O’Daniel’s onscreen text assumes its own dramatic role. Using punctuation, colours, CAPS, timing, and tempo, the text playfully interacts with the sound, or absence of sound, to tell another story.

POV spoke with O’Daniel ahead of The Tuba Thieves’ Sundance premiere (and before the captioning controversy) to discuss the creative process behind this unique work.

POV: Pat Mullen

AO: Alison O’Daniel

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: How would you even classify The Tuba Thieves in terms of genre?

AO: I don’t classify it, but that’s maybe my rebellious nature. It has elements of straightforward documentary and then it has very fictional, narrative elements. I’m also a visual artist, so some aspects have the quality of an essay film or video art.

POV: What was your approach to making a film about the tuba thefts that wasn’t about the actual thefts?

AO: That was the very first decision I made. I started hearing stories on the radio and thought it was a quirky story. When I heard the story the third time and then the fourth time, I started becoming aware that the reporting was so focused on the thieves. I had so many questions about what was happening in the high school rooms. I had this image in my mind of high school students sitting in class listening. I started reaching out to the band directors and visited whoever would have me. It was funny because when I went to Centennial High School, they were just like, “Eh, it’s not that big of a deal. We just switched to trombones.”

So I decided the film would be called The Tuba Thieves, but in a rejection of the way the story was being told in the news. I wanted to make a film that was a listening project, as I’m d/Deaf/Hard of Hearing, because deaf people are hyper-sensitized to sound. We have to think about it every single day, so the project became about sound being taken away and the ownership of sound.

POV: How do you make a soundscape for a film as a director who is d/Deaf/Hard of Hearing?

AO: I went down to Mexico and worked with sound designers at Splendor Omnia, which is the home and production studio of Carlos Reygadas, who’s one of my favourite filmmakers. I love that the sound of the film was done in Mexico because of the relationship between Los Angeles, the tubas, and Banda music, and to Mexico specifically with this story and the speculation that the tubas were on a black market and going into Mexico.

When I’m on the ground working with the sound designers, there are moments where I get ear fatigue and I have to lean on the people that I’m working with. I’m directing and then I’m taking a step back and letting them direct me. That’s true for all the collaborations I have, whether it’s cinematographers who I’ve directed to move through cinematography with their ears. With the sound designers, I’m very vulnerable with them in some ways. I only really work with people I trust, but I sometimes have to have to say, “Please don’t soundsplain to unless I ask you to soundsplain to me.” With this team at Splendor Omnia, they were sound nerds and I loved them for it.

POV: When I was researching the story, most articles I found speculated that the tubas were stolen for Banda bands in Mexico. Did you find any truth to that story?

AO: That wasn’t my interest or angle at all, but I was interested in the subjects of the film. Sam Quinones, the LA Times writer, has done all that research. Sam Quinones was one of my main sources about the tuba thefts. When I went to visit Southgate High School, the students had this story about a student who had been in the class when they decided which instruments they’re going to play, and then literally the next weekend all their tubas were stolen and they never saw that kid again.

When I told Sam that story, he said, “I don’t know how one person could do all this. It’s possible they had plants.” It’s an interesting story as a phenomenon in L.A., but I was never interested in telling that story. I didn’t feel it was my story to tell. In some ways, it was part of the fabric of the entire story, which is about what happens when the sound is taken and what that means. If sound can be taken, then that implies it can be owned.

POV: What was your “casting process” in terms of the sounds you use in the film, like the quietness of walking on leaves in socks?

AO: I consider this film a listening project. The man walking through the forest in his socks is a fictional character. In the script, he’s called the Irritated Man. He gets up and he leaves John Cage’s seminal avant garde performance of 4’33”. [4’33” is a three-movement piece in which the musician performs not a single note during the duration of the concert.] When that piece was performed in 1952, it had this seismic effect of making people think bigger about what music is and can be. I accidentally stumbled into telling that story. I started the film with three musicians who I asked to make musical scores before I had written the film.

I wanted to make the film backwards. When I asked these composers to make music, they didn’t have anything to respond to, so I gave them references. I was trying not to predetermine the narrative, so I gave them random references. For one of the composers, I gave her news stories about the tuba theft, but I gave another one a picture of the concert hall. I didn’t know that picture was of where John Cage premiered 4’33”. He [the composer] was amazed by that and said, “You’re d/Deaf/Hard of Hearing and you’re working with all these deaf people. You have to do something about 4’33”.” I had a little resistance because 4’33”, to me, has this mythology that it’s about silence. Once I connected that the mythology about deafness is that it’s also about silence, then I became interested in it. That’s how I decided to write this character who leaves 4’33”. He can’t handle it. He rejects the concert, and then goes out and has his own experience. I also happened to participate in a friend’s dance workshop. Someone in the workshop taught us how to stalk prey, like how a predator walks through leaves getting down close to the ground and moving its feet so that they won’t make any sound. I taught the actor the same thing that I had been taught. I told him to move through the space of the forest without making any sound. That was the direction.

POV: What about the sonic boom? That comes up early in the film when one character talks about how he has a scar because he was sitting in front of glass and it shattered as a plane went by. Then there’s the story of the neighbourhoods disrupted by airplanes flying overhead.

AO: That’s actually my mom’s story and I guess it’s my story too, except I don’t have a scar and no glass shattered on me. I was born in Miami, Florida, and all these planes would fly overhead and there would be these sonic booms. People in the neighbourhoods underneath would get frustrated.

It’s a play on the idea of breaking the sound barrier. I hope this film is breaking a sound barrier between the deaf and the hearing. That’s why the sonic booms came in. Because of the topography of Los Angeles, the sound of the city really flows. A lot of people can’t tell the difference between the sound of the ocean versus the sound of traffic. There’s this kind of hum, whereas in New York, it’s percussive. People use their horns and it sounds like a jackhammer hitting a building. In L.A., everything is flowing and traffic almost becomes a beautiful soothing, whooshing sound. Even the planes, the air, and the helicopters make a hum, so being in that city became part of the sound design. I stumbled across a story about the neighbourhood Surfridge and how it was eminent domained. Children were losing their hearing from living in proximity to LAX as it was being developed. I was constantly aware of these stories coming up and those stories determined the sound design.

POV: You also did parts of The Tuba Thieves as installations. How can you explore sound differently in an installation piece with screens versus a feature?

AO: When I started making this film, I had a feature script. I just didn’t know how filmmakers raise enough money to do it, but as a visual artist, I knew how to apply for grants. As I started getting grants, I needed to figure out what could stand alone from the script. I made short films and then was invited to show them. When I went to see a space [in 2015], it was this cavernous concrete place, and the sound was awful. I found it very ironic. When I show things in installation, the sound of the space in which I’m showing it becomes part of it. One time I was invited to have a show at a place and as I was getting to know the space, this huge HVAC system came on. I was like, “Oh my gosh, these walls are the outside of an HVAC?” It was so interesting to me because the whole show became about the HVAC. I think because I’m d/Deaf/Hard of Hearing, I’m unwilling or unable to ignore sound. The sound of a space becomes a part of an installation whereas a feature film is more self-contained and isn’t interfered upon. Obviously when you go into a theater, you’re at the mercy of whoever you’re sitting next to who’s crumpling a bag of popcorn, or the sound of another movie coming through the walls.

POV: The captions play such an interesting role in the film with how they add to the active viewing experience, like how a tuba note might be playing and the captions tell you about the sound the through the character spacing and the duration they’re onscreen, or how the concert scene has splitscreen and can be disorienting. There were times when I realized through the captions that I was missing sounds and had to adjust the volume, and when I went back, it was so different. What was your process for creating the captions in The Tuba Thieves?

AO: I made a specific decision to only have hard of hearing people do the captioning. Me and two other people did it. I’ve had so many frustrating experiences with captioning: either there’s just not enough, or the timing is off, and there’s censorship in captioning a lot of the time, which always confuses me. Or there’s just a music symbol for music–I think that’s the rudest caption because it’s telling you that something’s happening, but you don’t get to know what it is. When I started developing the captions, I felt like there was an opportunity to show what I want captions to do.

As directors, we’re constantly directing the eye and having you look somewhere so that you don’t look somewhere else, or so that you notice something or don’t notice something. With captioning, it was fun to think spatially with the frame and where sources of sound are located. There’s a moment where one of the characters skateboards and there’s a caption. Right before he skateboards past it, the caption disappears. And when he goes past another caption comes up. It was a process of having the narrative and the captioning interact and speak to one another.