The Stand

(Canada, 94 min.)

Dir. Christopher Auchter

Standoffs fuel a current of Indigenous resistance and resilience in Canadian history. These moments in which members of First Nations communities stand their ground and defend their rights, lands, and histories frequently mark turning points in the national collective consciousness. They’re also material for some very fine and continually resonant documentaries, including, but not limited to, Kanehsatake, Blockade, and Yintah, to name a few.

Add Christopher Auchter’s impressive NFB doc The Stand to that list. The all-archival film revisits the events of 1985 when a group of Haida people assembled on a muddy road on Lyell Island. The footage shows how they stood in solidarity and refused to let the heavy trucks of Frank Beban Logging pass. Auchter’s film shows how cameras quickly descended upon Haida Gwaii to capture the standoff between the Haida people and the loggers. The cameras can’t help but take in the beautiful lush greenery of Haida Gwaii that the protesters defend. But, in turn, they also can’t ignore how brutally the logging ravages, scars, and devastates the landscape. Pundits on the news call the land defenders criminals, but don’t seem to mind the footprint left in the name of big business.

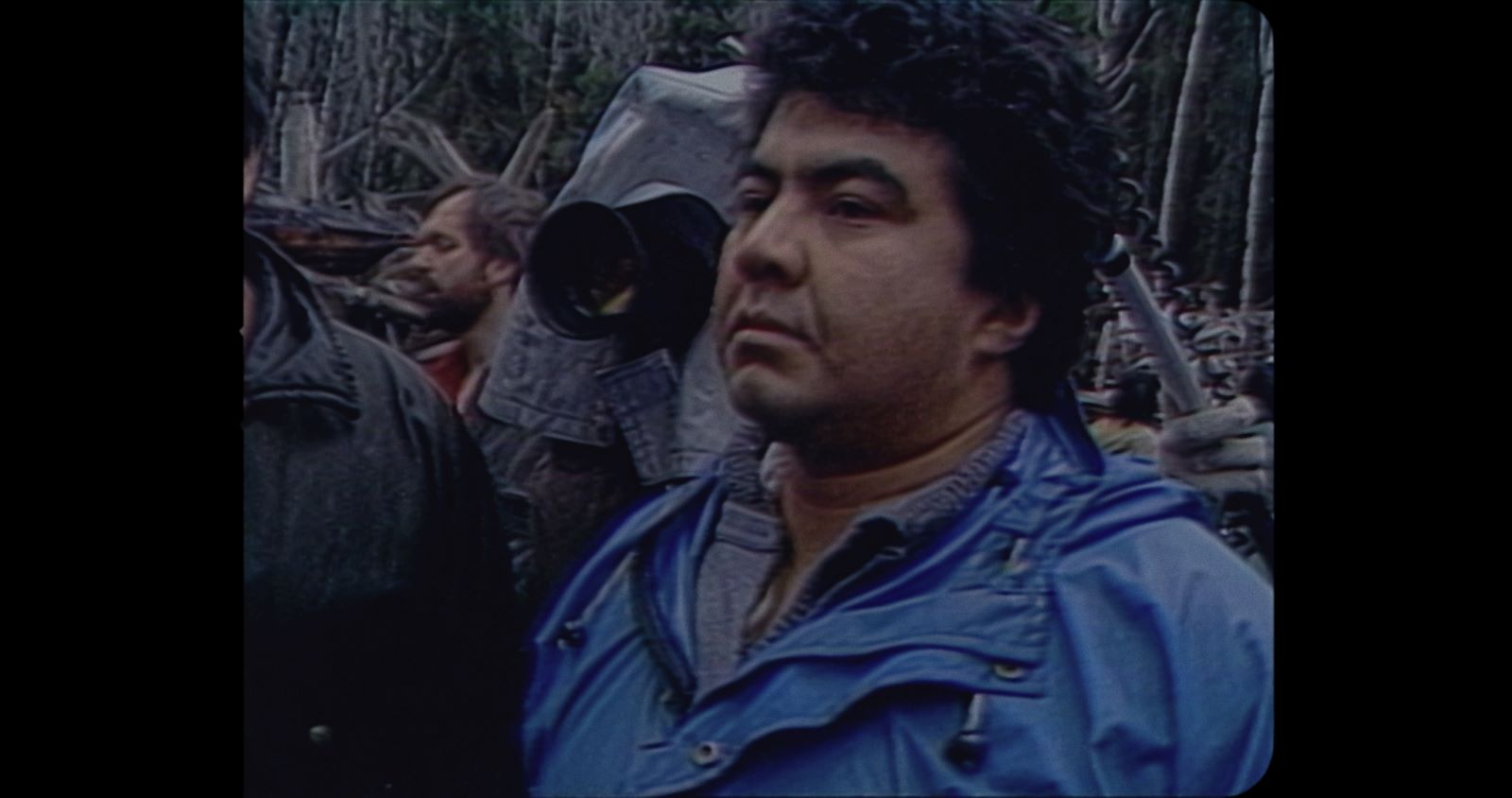

The standoff becomes embodied in the voices of two men. On the Haida side is leader Miles Richardson, who serves as the main spokesperson for the nation both at the blockade and outside in the media. On the other side is Frank Beban, who asserts his company’s right to log on the land and has the paperwork to prove it. But Richardson’s clear that Beban’s permit is worth beans when the Haida never ceded that territory. The standoff assumes national significance for the precedent the case entails: who has jurisdiction over unceded land?

The interest in the case is evident in the impressive range of footage that Auchter provides. There’s extensive coverage of key scenes drawn from over 100 hours of news material. Confrontations play with riveting shot/reverse shot exchanges. Although the low-res video (and 1980s’ fashion and haircuts) risk dating the material, it feels very much in the present tense. There’s enough coverage of key scenes to provide all the voices and perspectives with the tempo of a dramatic shoot.

One must also appreciate the efforts of those journalists from years ago because The Stand isn’t a tale of a violent confrontation. It’s a snapshot of civil and respectful dialogue between feuding parties. Auchter gives space to both sides of the story. There are some genuine learning experiences here as Haida leaders and settler workers exchange viewpoints. Both parties understand the forces that motivate each side while a cultural view of the land—something to be nurtured versus something to be conquered—proves an irreconcilable ideological divide.

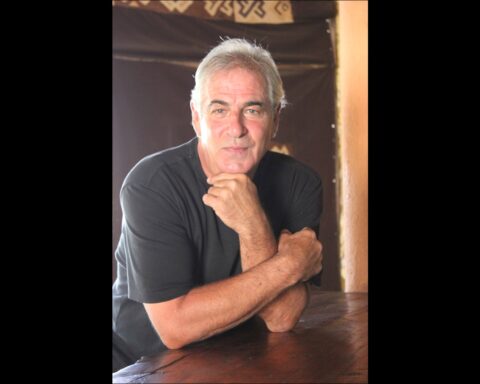

In between images of at the blockade are sequences of another standoff, one between Richardson and TV blow-hard Jack Webster. The latter gives Richardson room to speak and Auchter employs their sparring match as the film’s narrative frame. Webster seems to get all the issues at hand and, in fact, articulates them fairly well. But he personifies a faction of the unmoved majority as his questioning assumes the settler way as the norm.

Webster, RCMP officers, and politicians across the land aren’t moved, either, as Haida grandmothers take position on to the front lines. The film observes as elders become the island’s first line of defense. Their exchanges with the RCMP follow the standoff’s habit for civil dialogue and non-violent resistance. When it comes time for their arrest, officers allow them to walk escorted by their sons, rather than by officers. They set examples for younger land defenders carrying the fight.

The Stand pays homage to the elders with an animated figure, Mouse Woman, who appears throughout the film. On one hand, Mouse Woman serves a practical function. Speech bubbles appear with her shape-shifting mouth. She provides context and bits of information that’s absent from the archives. At other times, she offers a dramatic and thematic presence. Mouse Woman shadows the land defenders as a sort of mystical guide. However, the animated conceit, while a refreshing alternative from static title cards, occasionally proves distracting. Particularly when she seems to interact with the archive does Mouse Woman somewhat break the riveting tension.

On the other hand, this benevolent figure underscores the theme of defending the land and having a relationship to it. The contemporary current in the fresh animation evokes the ongoing nature of this fight, which continues as the Haida Nation protects the islands in the face of shipping and industry that threaten a long-preserved ecosystem. The images may be decades old, but this stand is timeless.

The Stand premieres at the 2024 Vancouver International Film Festival.

Update (June 2025): The Stand streams at NFB.ca beginning June 19. It screens at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on June 21.