People’s Park has won kudos for its technically admirable long, slow, intently wandering seventy-five minute one-take shot of a lively central park in Chengdu, China. The film is impressive in its use of the pan as a subtle narrative device, allowing the viewer to catch short glimpses of passers-by and speculate on the backstory of each of the minor characters who wander in and out of the frame for seconds at a time. In People’s Park, the camera doesn’t pause for any extended period of time to focus on one individual park-goer but, rather anthropologically, collects a wide swath of park life. There is never a feeling that the Western filmmakers are exoticizing their Chinese subjects who pass in and out of the frame; instead we as audience members are sharing in the enjoyment of the park: it is people watching taken to cinematic heights.

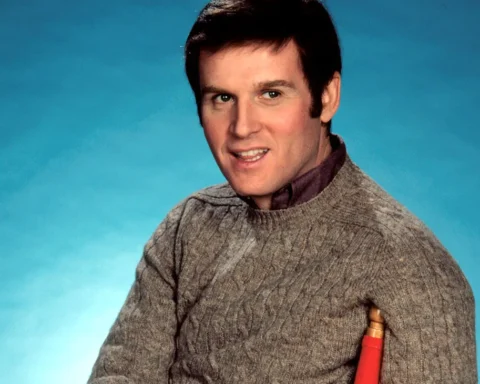

I chatted with co-director J.P. Sniadecki about his interest in China and filmmaking process. “I got interested in China as a younger person reading Chinese philosophy,” says Sniadecki. He landed in China in 1999—on his first airplane trip anywhere—on the day that NATO forces bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during the Balkan Wars. That day, he was stopped by the cops at a rally protesting American hegemony. “From that day on,” he says, “I just told everybody I was Canadian.”

I asked Sniadecki how he came up with the idea for People’s Park. “I had [already] made a couple of films in Chengdu and had spent a lot of time in that park. When you are…[there], you have a sense of all the wonderful concentration of different pockets of performance…. Sound bleeds over from one area to another and you’re caught in that in-between space. Not quite in one pocket of performance, both soundscapes start to mesh and blend in interesting ways… I wanted to capture this wonderful unbroken continuation sonically but also spatially, anthropologically, architecturally, and cinematically.”

The film is indeed impressive in its unpredictable and organic sonic architecture, always surprising the viewer and helping subtly direct attention from pocket to pocket. Sniadecki and co-director Libbie Cohn shot their beautiful one-take film over three weeks using a wheelchair to capture the long take through the park. “It was the best and cheapest and most flexible way to capture one shot,” he said, “it’s an old school way of making a dolly shot.” There was also a certain cinematographic economy with this method; the take you see in the film is number nineteen out of approximately twenty-four full takes (and forty-eight attempted takes). “We built an itinerary over time, with lots of different audible variations. Some takes lasted two hours, others lasted 43 minutes.” When I asked what his inspiration for the film was, Sniadecki didn’t recite a predictable list of documentary influences. He and Cohn wanted the film to mirror a famous Chinese scroll, the Song Dynasty-era panorama Along the River During the Quingming Festival, which Sniadecki said is known for “democratically capturing all walks of life, material, and culture… this is a twenty-first century digital homage to that long, long, beautiful scroll.”

“I still go back (to China),” Sniadecki tells me. “I went back for the Beijing Independent Film Festival, but it was never held…[It was] a very sad moment where most people were just sitting around… there were a few melancholy dinners but that was the extent of it,” he says, referring to the sudden closure of that important independently organized event, which helped local documentary and experimental filmmakers showcase their works within China. Ironically, Sniadecki told me that government-sanctioned film festivals, such as the Qingdao Film Festival, set to open in 2017, have huge budgets in hopes of attracting foreign investment to help westernize Chinese cinema.

Cinema on the Edge, the organizers of the current traveling series of films that had initially been curated by the organizers of the Beijing Independent Film Festival, are taking Chinese documentaries like People’s Park abroad as a response to the closing of the festival. It’s clear that Cinema on the Edge is playing an important role in exhibiting these overlooked films abroad, exposing savvy and concerned art house audiences in North America and Europe to a nuanced China driven by personal storytelling.

J.P. Sniadecki now teaches at Northwestern University’s Documentary Media MFA program, where he’s excited to attract a lot of international talent, including students from China. While his academic schedule keeps him firmly planted in the US for now, he does plan to go back to China. He has a few projects in the works right now, including an adaptation of the famous Chinese novel, The Water Margin, the Chinese equivalent of Robin Hood and His Merry Men.