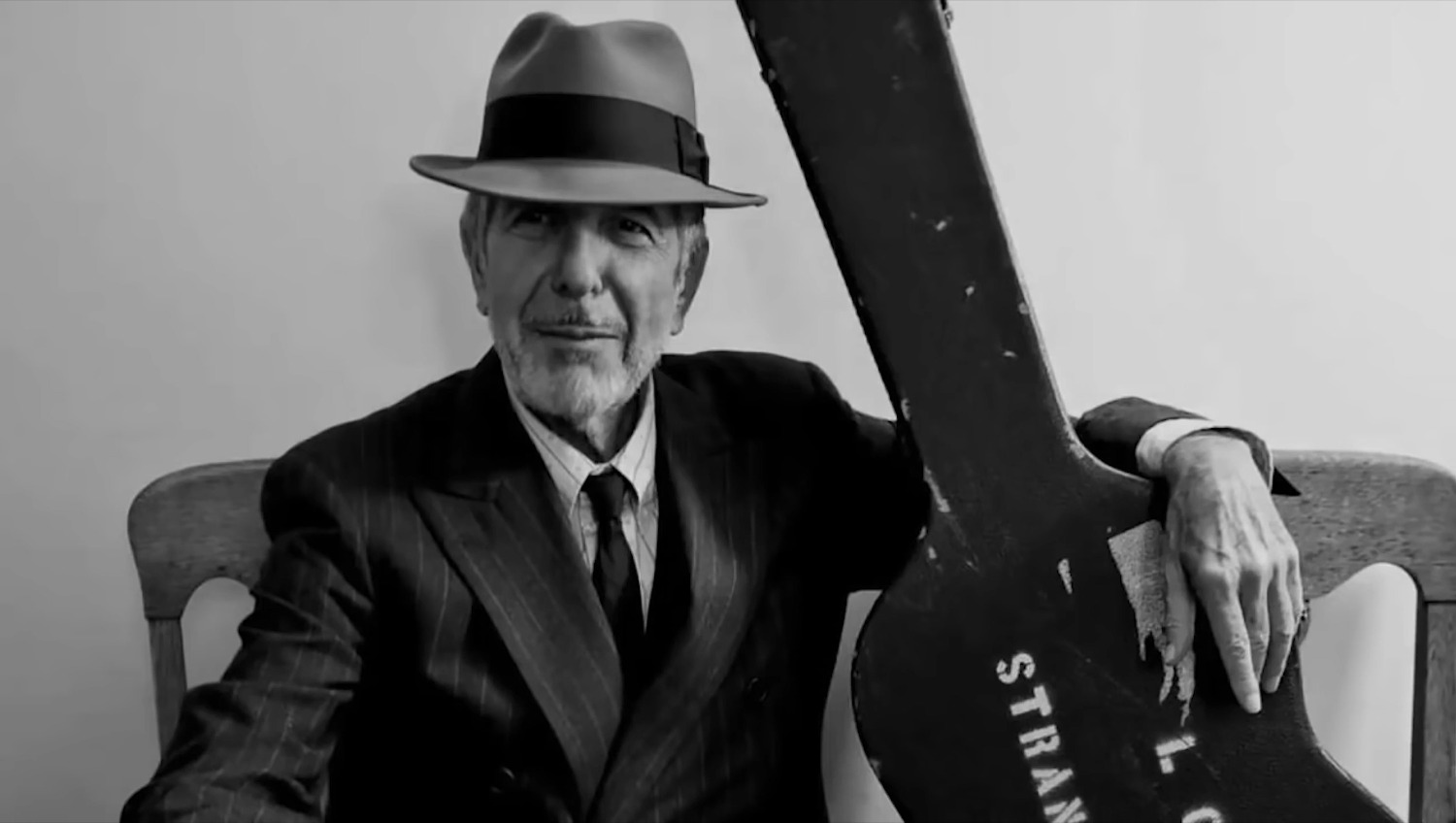

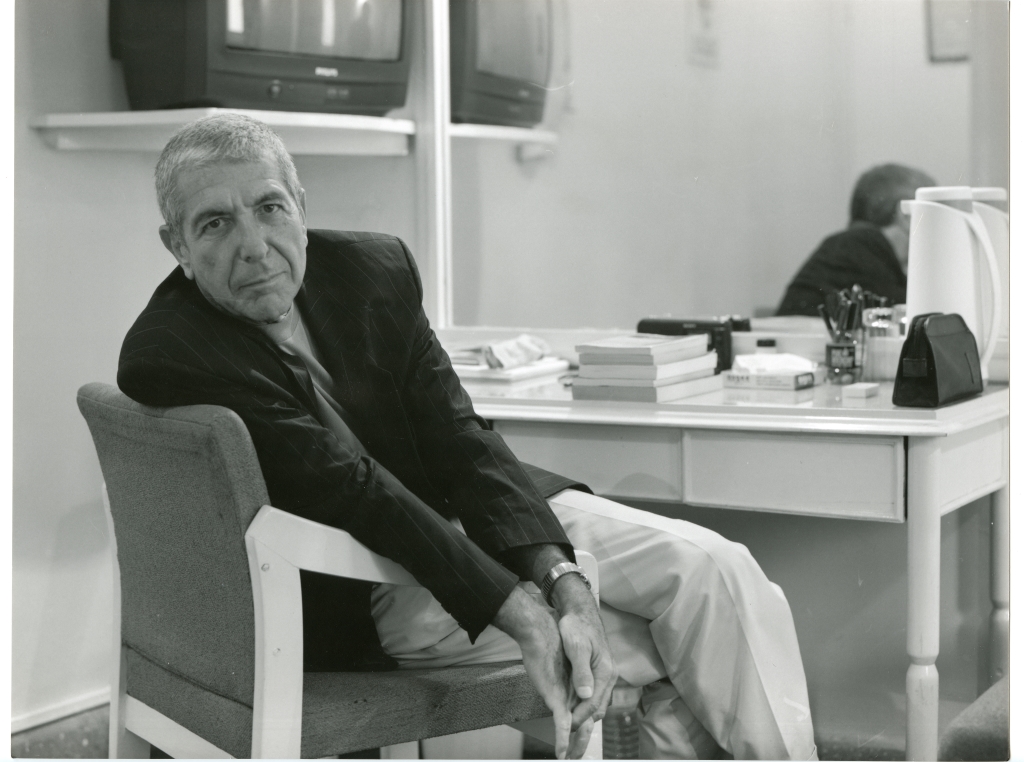

Of all the iconic Canadian musicians who emerged during the’60s and ’70s, none was more iconoclastic than Leonard Cohen. A poet born of privilege, a late starter with a lascivious air and suave style, he sometimes felt out of place among a generation newly fascinated by vibrant and flowery youth. It was as if Cohen was born to appear as a wizened curmudgeon, part Talmudic scholar and part rakish ladies’ man. Like Mordecai Richler, a fellow Montreal Jew, he embodied an acerbic, dark, charismatic air that was immensely inviting. He sang of blowjobs with bemusement and wrote prayer-like odes to an indifferent holy spirit, all presented with a growling baritone that became more intoxicating as he grew into its weathered, aged timbre.

On the one hand, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song, the fabulous film from Emmy Award winning filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine (Ballets Russes), is an unabashed celebration of Cohen. It shows in profound ways how the artist’s own spiritual journey provided some of the most exceptional music of an exceptional era. However, Hallelujah isn’t merely meant to thank the gods for gifting us with such a character. It’s also a fascinating, probing look at how one person’s art is shaped not only by audiences who are moved by it, but also those that end up reshaping it. Cohen’s most famous song is known by millions because of a cover of a cover. Geller and Goldfine acutely present how the adoration of this track occurred and how Cohen’s own journey with “Hallelujah” culminated with what easily could have been a forgotten track from a rejected record.

Hallelujah debuted last fall at Venice and Telluride, and it seems all the more preposterous that a work of such local interest couldn’t have found a home at TIFF 2021, but those are perhaps uncomfortable questions for others. Regardless, here in the Summer of 2022, the film is finally making its way to local theatres. It’s an absolute must see for any with a love of music, Cohen’s or otherwise.

We spoke to Geller and Goldfine prior to the film’s Canadian theatrical run.

POV: Jason Gorber

DanG: Dan Geller

DaynaG: Dayna Goldfine

The following has been edited for clarity and concision

POV: Let’s talk about Lenny. How were you introduced to his music?

DaynaG: My connection to Leonard and his music was more subliminal until we actually went to see him in concert. I believe that was 2009 or ’10 when he came through the area on that amazing five-year victory lap tour around the world. We were fortunate enough to have friends who took us to see him in Oakland at the Paramount Theatre and the rest is history. It was just this gobsmacking, life-changing performance.

DanG: We were knocking around the idea for a film. We weren’t quite sure what we wanted to do—it had been about a year since we’d finished The Galapagos Affair. David Thompson, the wonderful film writer, mentioned something about a book about a song, maybe a documentary about a song. That’s when the gears started turning and by the time we were at dessert, Dayna said, “Oh my god, what about Leonard Cohen and that song ‘Hallelujah’?” That began the research to start to see what really is going on with Leonard Cohen and that song and the depth of his incredible career.

DaynaG: For me though, it wasn’t just that his songs are great. It was the indelible image of seeing him at that Paramount Oakland show and watching him get to his knees as he started singing “Hallelujah.” It’s an image that is just burned into my brain. I’ll never forget it and it kind of came to me whole cloth after we discussed the concept of doing a documentary about a song.

POV: Based on that, did the Jeff Buckley cover version mean something to you potentially even before you the Cohen concert?

DanG: We first heard Buckley’s version at a friend’s house. Dayna and I bought Buckley’s Live at Sin-é CD box set when it was published in 2003. We played it over and over—not just “Hallelujah,” but we weren’t coming through a Cohen phase yet.

DaynaG: I could easily be among that quick montage of people in our film who are all saying the name Jeff Buckley when talking about the song. That was my introduction for sure.

POV: I love how the film deals with Leonard Cohen in a way that Leonard Cohen would have dealt with Leonard Cohen: with a sense of ironic detachment, of the surrealism of it all, and a recognition of both the comic and tragic nature of all of this. You had to get the tone right because you’re telling the story, of not only a man and his journey, but also a song. Can you talk about threading all of that together?

DanG: That [tone] was extremely important to us since it was a story about a spiritual journey as much as anything. It reflects the complexities of Leonard’s spiritual journey, which was wandering and serious and questioning all at once.

DaynaG: Our mission from the beginning was to tell the story of “Hallelujah” and tell Leonard’s story through the prism of that particular song. It freed us up in some ways. We didn’t need to do a cradle to grave, nitty-gritty biopic. We could really go along with his spiritual journey, which is what we thought reflected the journey of that song.

One of our rules of thumb early on was this notion of why is it that we think that Leonard Cohen is the only man in the universe who could have written “Hallelujah?” In order to get to the bottom of that question, you need to know a little about Leonard and his spiritual quest and his sense of the world and that guided us.

DanG: But the balance was not instant. The scales were wobbling back and forth through various cuts of the movie. We would test cuts on friends who we trust and who understand our artistic process enough to know that it wasn’t a finished movie. As it got closer to its equilibrium with tiny little adjustments, we got to a point where it seemed for most people that they were understanding the film as its unity rather than as two completely separate movies.

DaynaG: We were trying to give Leonard his due, which meant not being afraid to take time in the editing room. It wasn’t just “Hallelujah” that he spent four or five or six years or seven years writing. A lot of his compositions took quite a bit of time, so we were like, “This isn’t a race against the clock. Let’s take as much time as it takes to get that balance right.”

POV: I have a rule about music docs. It’s a very simple rule: if you hate the band, does the film still work? I was very skeptical going in, but this really is a beautiful film about music in general, and more importantly, how a song is taken away from an artist once it is unleashed. You say it’s Leonard’s spiritual journey, but it’s our spiritual journey as well through music.

DaynaG: Brandi Carlisle says towards the last third of the film that what’s so remarkable about a song if it struggles and makes its way out into the world against all odds is that it ultimately becomes its own thing, almost its own person. That’s what happened to “Hallelujah.” As filmmakers and artists, it was really gratifying to see that there are times when a good piece of work gets past the gatekeepers. I think that’s something to celebrate and give people hope.

POV: I knew a bit that Cohen had crafted both secular and the religious versions of the song, but I had never done the Talmudic dive on the variations, with what John Cale did, the Shrek version, and so on. Many of us hold up the poetry of Leonard Cohen on a pedestal, yet this song is evidence that even when the words are ripped apart from the artist, people respond to it. Your film shows that the audience inevitably will take ownership of it through different versions.

DanG: That’s a different take. I hadn’t thought about it that way, but you’re right.

DaynaG: Also, Leonard himself had a changing relationship with the song. The John Cale version worked into what it because he had gone to see Leonard when he played at the Beacon in the late ’80s and then thought he might want to cover the song and do his own take on it. But then “Ratzo” Sloman, the journalist, said “You know, there are two versions: there’s one on the album and then there’s one that you heard. You really ought to get both of those things and Leonard’s relationship with the song.” When you see Cohen in the five-year concert tour at the end of his life, it was very difficult to cut that montage of him singing it around the world. He picked different verses at almost every concert and every location, I’m guessing that it depended on what he was feeling that day.

POV: If you look at the Rolling Stone 500 songs list, the cover-of-a-cover, the Jeff Buckley version, is on there. The number one song is “Respect,” which Aretha “stole” from Otis’ original. Another is Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” and Dylan never played it again his way afterwards. Songs shift and songs are shaped, even for the artist. This is a film about Leonard Cohen, it’s a film about his song, but it’s also a film about music, and that’s what I think is so fundamental to its success. How much of that was conscious for you guys while making this?

DanG: I play guitar and I’ve always got my ear cocked towards the music and how it’s affecting me. Brian Monaco, one of the executives of Sony Music Publishing, had seen a fine cut of the movie. We had licensing to do with him and wanted him on board to understand what we were doing even though we’d made this film independently. Brian’s first reaction was that every budding songwriter in the world needs to see this movie. The film tells you a lot about the process of songwriting—not just craft, but the kind of thoughtfulness and refinement that goes into making music that can then transcend itself and be adopted by various audiences and other artists. It can be taken away from itself and become its own little gem and its own gift.

[T]here are a lot of documentaries that that have an ostensible subject, but the rumbling underneath is what the movie is really about. The ostensible subject can be done with beautiful artistry, but what always gets me is the rumbling beneath. – Dan Geller

POV: Were there specific other films you looked at in terms of editing or tone?

DaynaG: 20 Feet from Stardom. Morgan Neville came on early as an Executive Producer and he gave us a lot of street cred.

DanG: The film was done at that point, having premiered at Venice and Telluride, but watching the Peter Jackson Beatles: Get Back documentary, I looked at that and knew that’s the tone, that’s it. You’re watching creativity, you’re watching the struggles that are involved and also the moments of sheer inspiration. There are moments when something just happens and it’s staggering. A beautiful thing arrives.

One of my favourite sections of the film has to do with Rabbi Finley talking about the Bat Kol, the feminine extension of creativity and God into the creator’s mind. You receive inspiration, you don’t know where it comes from, and then the work is to polish, polish, polish. That notion of receiving something and you don’t know how and you don’t know why is, for me, part and parcel of all creative process. They don’t have to be movies about the arts, but there are a lot of documentaries that that have an ostensible subject, but the rumbling underneath is what the movie is really about. The ostensible subject can be done with beautiful artistry, but what always gets me is the rumbling beneath.

POV: Morgan Neville is the master of this. He’s the master of whatever he’s talking about: Yo-Yo Ma, Springsteen, backup singers, or Bourdain. It doesn’t matter: you’re getting something precious about the preciousness of humanity.

DaynaG: Exactly. When he came on as E.P. it was just a very gratifying moment, because I admire his work so much.

DanG: Morgan and Dayna and I got into the Academy the same year. There was a little party, and we just clicked and became friends from that moment. When we were starting this movie, we went to Morgan because we knew he’d be smart about giving us feedback as part of our circle of trusted advisors. He also helped out with some things when we needed to do a shoot in L.A. This is the level of the person: at the very end, he asked with timidity if it would it be okay if we put “in association with Tremolo” at the end of the credits. I said of course we would do that!

POV: Let’s talk about the fundamental difference between this film and your previous works. What type of subjects were you looking at before, and were any nearly as mercurial as Leonard?

DaynaG: A common thread to all of our work, as Dan alluded to earlier, is that there’s a surface subject, and then there’s the subject that’s floating underneath that that may never necessarily be apparent. We think it adds to the emotional content of the film. For instance, Ballets Russes, which, on the surface, is about a ballet company that brought ballet to every place around the world. We got to interview all these people who had performed for various incarnations for 50 years, yet what it was really about wasn’t ballet so much as what person looks like if they’ve spent their entire lives living for the arts and fulfilling their own dreams, and choosing to do that without thinking about making money.

POV: Do they look like documentarians?

Both: [Laughter.]

DanG: I think about our non-arts films, like The Galapagos Affair, which, on its surface, is about a murder mystery that happened in the 1930s in the Galapagos Islands with a little group of people. The underlying theme is that wherever you go, you bring yourself. If you have problems, you will bring the problems. There’s no escaping civilization because you are civilization. Or for Frosh, we lived in a college freshman dorm for a year. Yes, it’s the American rite of passage, but underneath that, the film is about what happens when you put students from different races, different classes, different religious beliefs into a pressure cooker of a building and they cannot escape each other. When they are stuck in that dorm for a year, what starts to happen?

My thesis film was about the Sundance Filmmakers Lab when it was in its infancy. I had to show the final film to Robert Redford. He said afterwards that it’s great that the film has a sense of humor. He said it’s really important and not present enough in documentaries that there is a sense of humor. I think all of our films have a sense of humor.

DaynaG: We don’t always know what these undercurrents are when we’re starting on a project. I think we’d interviewed about a dozen of the Ballets Russes dancers before I turned to Dan and said “Oh, wow—now I get it.” I think I’d just turned 40 and was looking for role models in the aging process. So, selfishly, that’s what this project was for me, but if you would have told me that before we started, before we picked up our camera and microphone, I wouldn’t have got it.

POV: The greatest documentaries are those where the director has the courage to follow the story instead of follow their précis. How did this story shift?

DaynaG: It shifted a lot. Originally, we were thinking of a three-pronged braiding, which was the history of the song, then Leonard Cohen, the man, the spiritual seeker, the artist. Then we were going to have a third strand where we were going to follow a couple of artists, maybe two or three, who had never covered the song, as they unpacked it for themselves. That was going to be a vérité strand. We started reaching out to people and we were moving along in that direction, but we ended up editing the first act without that. We showed it to Hal Willner—he was our music guy and was going to cast that strand for us. He looked at the first cut of the first act, and he turned to us and said, “You guys don’t need that.” This is a different film and so he put himself out of a job in a way.

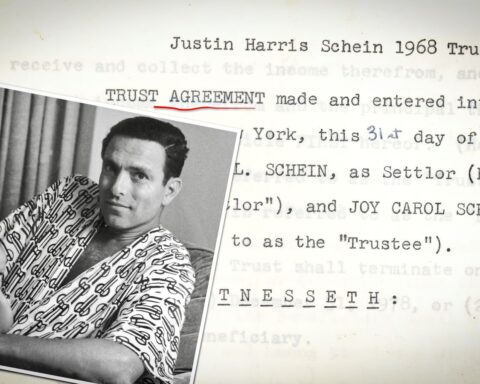

DanG: The balance increasingly shifted to Leonard the seeker and Leonard the deep soul. When we started the movie, I didn’t think we would see those two elements line up with each other in an equal balance. I thought it would be much more about the song, with enough of Leonard in there to support questions about why this song. We listened and listened. We were showing things to Robert Kory, who was Leonard’s manager in life and became the trustee of the family trust. We deeply believe in doing that with our subjects and began to accept this double-focus of the movie. It helped us access notebooks, Polaroids, selfies, and concert recordings.

POV: Can you talk about what you had to do to get these songs and if there were any creative restrictions, and therefore creative opportunities, about what you need to do to get licensing?

DanG: There were none and that was critical to us. It’s always been the case with our movies, on the ones we generate ourselves. The access developed out of a matter of trust over time. Robert, the more he saw what we were doing, the more he felt comfortable with what we were doing. He began to see that the Leonard he knew and knew well was showing up on screen in all of that complexity. It took him a long time to admit that the notebooks were still extant, to show us the notebooks, and then to give us full access to the notebooks. It took a while for these things to manifest, but there was never any moment of creative discord where he would say this is not what Leonard would ever would have wanted. He had a couple of factual challenges for us, which, of course, we were thankful for, and corrections of some misperceptions that had been published elsewhere.

DaynaG: He would pose questions to us more than anything. For me, one of the most valuable challenges he threw down was about those who believe the only reason Leonard went back out on the road in his mid-70s was that his manager had stolen his money. Robert let us know that it’s a lot more complex than that. That’s when we started really plumbing the archives and listening to what Leonard was really saying. He says, “Look, you know, 70 is not deep dark old age, but it’s definitely the foothills of old age and I’ve got a certain body of work that I want to complete and I’ve never really given up this dream of fulfilling my full potential on stage.” Yes, it was the financial thing, but it was this other thing too. They just coincided. The fact that Robert encouraged us to look beyond the obvious, what had already been written or said about Leonard’s decision to get back on the road, was a huge gift.

POV: But was it strictly fair use that you get to use k.d. Lang, Steven Page, etc.?

Both: No, oh no.

POV: Beyond Leonard, you have access to everything. I spent most of the movie, again, cynically thinking, “I guess they didn’t get k.d. Lang,” and then boom at the end, I’m like, “Of course, what a perfect space for that to be.” It’s literally her culmination.

DaynaG: And you don’t need her to say anything.

DanG: But we had to license everything. Access is different from licensing. We had an agreement where we paid the Cohen trust money, as one should, for access to some of these materials. We’re also going to give them all of the raw footage, all of the raw transcripts for scholarly research down the road.

DaynaG: What Robert Kory has said now several times when we’ve done joint Q&As is that had Dan and I come to Robert and Leonard in 2014 and said, “This is what we’re going to do, and we’re going to end up not just using ‘Hallelujah,’ but we’re going to use 22 other songs from your catalogue,” he feels pretty sure they would have turned us down.