Pushing boundaries to provide greater understanding for audiences is at the heart of those who work within the various structures of installation and multi-media art. Artists using such forms transport the viewer from the carefully curated confines of the physical and cinematic spaces into a realm that transcends time and space. It’s a place where one can meditate on the past, present, and future concurrently while observing how history, race, gender, and sexuality form the confines of our current state. Their works offer insight into the steps needed to remake society in a better and more inclusive place.

Artists have long challenged the viewer to reconsider the constructs of the world around them. Right now, there are many Black artists who are not only showcasing their prowess across installation works, cinema, and video, but also breaking traditional norms and expectations in the process. Individuals who can blur the lines between documentary and fiction, experiment with form and structure, and play with time and space in though-provoking ways help us to see the humanity in each other and examine history under an entirely new microscope.

Academy Award-winning director and artist Steve McQueen is one individual who frequently finds ways to immerse audiences in reflection by driving through the guardrails of expectation. Working within the realm of art galleries since the ’90s, he has used video installations, still photography, sound, distinct colours and lighting to shift between the concrete and the abstract. One can see his artist background on full display in his sprawling four-hour plus documentary Occupied City (2023).

Working with Bianca Stigter, the Dutch filmmaker and author who is also his wife, and her book Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945, McQueen’s film is an immersive and meditative look at the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam during World War II. Using only the audio presence of the narrator, Melanie Hyams, to add context, the documentary weaves stories of the past with images of Amsterdam during the COVID crisis. Creating a timeless and timely aura, McQueen’s approach allows both the horrors of the Nazi regime and the resiliency of the human spirit during the pandemic to resonate. By layering tales of terror and injustice over images of Amsterdam during the past and present, the film collides in fascinating ways that lead audiences to contemplate ethics and mortality.

With two timelines running parallel alongside each other, Occupied City recontextualizes the world the viewers think they know. This is especially true in the way McQueen’s camera observes various historic buildings and communal spaces whose current serene demeanour hide untold traumas. In contemplating the shifting nature of time and highlighting the importance of memories which may no longer be visible to the naked eye, the documentary ultimately finds hope for the future in our ability to preserve and love. Occupied City is yet another reminder of McQueen’s ability to experiment with form to find the rich complexity of history and the joys and pains that come with human experience.

Erasing the lines of artistic conformity to explore history and memory is an area where Kahlil Joseph excels. A filmmaker, music video director, and video artist, Joseph has not only had his short films and installations displayed in museums and galleries from London to New York, but also created visually stunning and meditative music video works for the likes of Beyoncé, Travis Scott, and Kendrick Lamar. His works frequently focus on Black life in America, offering a humanizing lens that frequently moves beyond the white interpretation of Blackness. In his feature length directorial debut BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions (2025), Joseph adapts his 2019 two channel video installation into a genre defying and playfully dense cinematic work that offers an absorbing and profound meditation and celebration of Black culture. (The film has its Canadian premiere at TIFF in September.)

Partly inspired by the first edition of the Africana Encyclopedia, which his father gave his brother as a gift, Joseph’s BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions traverses through everything from the importance of exploring the Black history not taught in schools to Blackness’ impact on culture, art and fashion to Afrofuturism to Black love—and much more. Joseph’s film may employ the framework of a news program but, much like the recurring image of a record player used throughout, it plays like the ultimate DJ remix. It’s a work that takes time, memory, archival footage, fictional moments, the writings of W.E.B Du Bois, contemplations of the future, interviews, and social media memes to create an exhilarating experience unlike anything before it.

Influenced by Nigerian curator and educator Okwui Enwzor, whose views on the importance of the space between art and the spectator is something Joseph’s film takes to heart, as well as a YouTube clip of a conversation between Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman about “The Black Outdoors: Humanities Futures after Property and Possession,” BLKNWS breaks free of the traditional confines of what art can be. In doing so, the film forces the audience to reflect on the restrictions placed on Black art by those who displace and colonize it. The beauty and revulsions of the past and present are mixed in a vibrant tapestry of ideas and images that allow for the reclaiming of a history that is frequently stripped from Black art and culture.

The reclamation of that which was unjustly taken by colonizers is at the heart of Mati Diop’s mesmerizing documentary Dahomey (2024). Observing the transportation and resettlement of 26 stolen artifacts, out of the more than 7,000, that the French government is returning to Benin, formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey, Diop contemplates not only the theft of Black art and history, but the spiritual connections that the pieces have with the past and present. The film suggests that these are not just mere works of art, but rather each object embodies the soul of an ancestor. Taking the ingenious approach of having one of the artifacts, number 26, serve as an otherworldly narrator, Diop challenges the audience to put themselves in the mind and body of the various slaves who were abducted from their homes, and like the art the filmmaker’s camera observes being boxed up, transported across the sea, and imprisoned in the chains of servitude in a foreign land.

Dahomey captures how the distance from one’s homeland, 130 years ago in the case of the stolen works, can cause one to lose a sense of self. As number 26’s ethereal voice wrestles with both its sense of displacement and coming to terms with a home that now seems unrecognizable, Diop shows that the ancestors are not the only ones struggling to acclimatize to the rapidly changing landscape. The people of Benin/ Dahomey must also process what a post-colonial world looks like for them. Are the returning pieces a sign of progress and healing? Or is the fact that France is holding onto thousands of works an indication that they are still under the thumbs of colonialism? Furthermore, what process needs to be taken to ensure that the art works can be accessible to all so that history, their history, is not merely locked away behind glass cases like it was in Paris.

By imaging the soul of the statues as the film’s focal point, Diop creates a work whose dreamlike aura floats through space and time. This allows the director to reflect on the barbaric trans-nationalism practices, and the countless number of souls who died at sea during the slave trades, which ultimately built the colonial economic structures that now house many if not most of Black people’s stolen histories. In Diop’s skillful hands, the ocean is not merely a vessel for transportation, but a dangerous snatcher of souls.

Like a siren singing seductive songs full of promise and hope, the haunting nature of water is also felt in Diop’s documentary short Atlantiques (2009). In it, the director captures the bewitching allure, and hostile realities, of the ocean through the eyes of a recently repatriated Senegalese young man who is eager to attempt to make the trip back to Europe by boat. Despite his friends attempting to talk him out of it, by discussing all those who perished in his first attempt, the audience is always aware of the water’s pull on the man’s mind.

Diop’s feature adaptation of the short, Atlantiques (2019), won the Grand Prix at Cannes; it weaves a dreamlike quilt that is romantic and haunting. Using magical realism as the thread that brings the material together, the film contemplates the vicious impact of capitalism on Senegal and the ways class and gender play into the structures that keep individuals oppressed. It is the desire to break free that makes the frustrated young males in the film susceptible to the hypnotic allure of the ocean, an otherworldly taker of souls that always remains at the edges of the film.

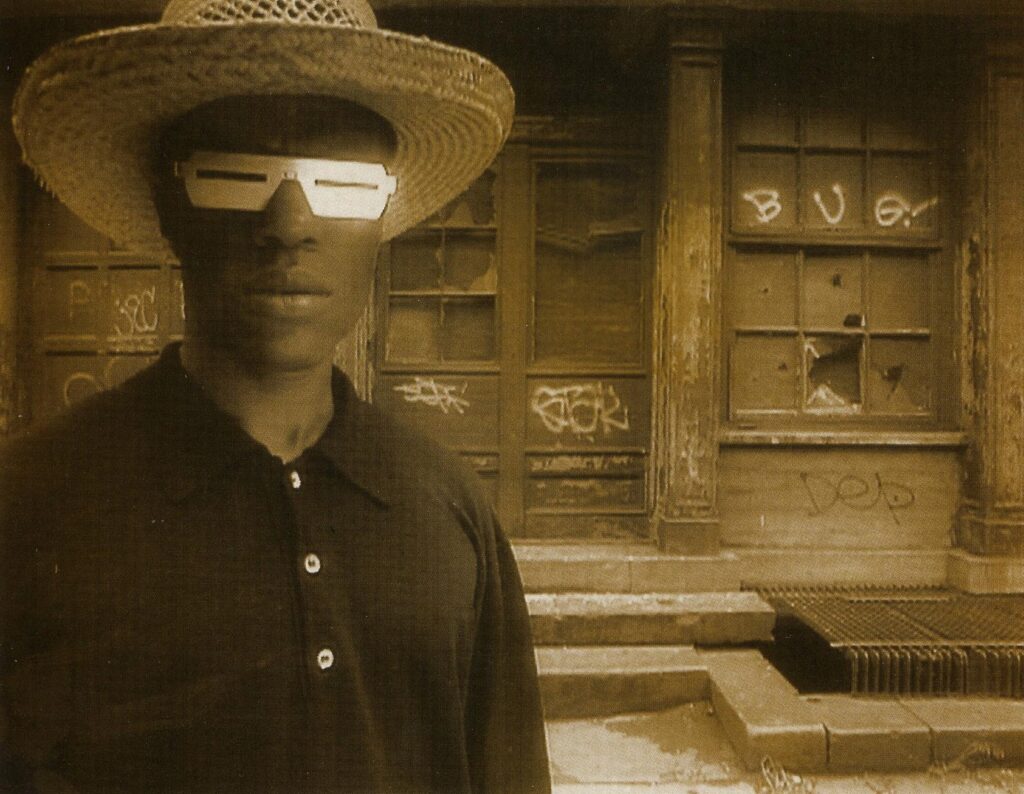

For Ghanaian-born British artist, filmmaker, curator and educator John Akomfrah, the vastness of the ocean also carries plenty of significance. His 2015 installation Vertigo Sea incorporates film and news footage to construct a gorgeous exploration of migration (both those fleeing persecution and those enslaved), the ways man inflicts harm on each other in nature, and how our consumption is negatively impacting the environment. The ocean becomes the central place where these aspects converge. While water is a recurring motif in his art, Akomfrah’s work frequently explores the struggles that come with being Black in British society. He is a founding member of the British Audio Film Collective, a group of seven multimedia artists and filmmakers who explore themes of Black identity through a poetic lens that often defies convention. Similar to Mati Diop, Akomfrah’s works reflect on the historical nature of displacement and the various forms that Black liberation takes. In his documentary The Last Angel of History (1996), the director uses the distinct musical styles of George Clinton, Sun Ra and Lee “Scratch” Perry and the notions of Afrofuturism to examine the way Black musical ingenuity continues to provide new means of connection.

Blending documentary with fiction, Akomfrah encases the film in the narrative of a fictional “Data Thief” who travels space and time in search of a code that will unlock the future. The film plays with the notion of memory and reconnection by using the African drum and other forms of Black music as key to not only getting in touch with our roots but connecting on an extraterrestrial plane. As one writer that Akomfrah interviews notes, Black existence and science fiction share many similarities. Black people are often treated as the “other” in white society. They’re rarely believed and frequently fight to have their existence and humanity acknowledged.

The ability to see and define oneself on one’s own terms, and not through the preordained shackles that whiteness has placed on Black people, is one of the frequent themes in the works of Isaac Julien, a British filmmaker, professor, installation artist, and the co-founder of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective. In The Passion of Remembrance (1986), which Julien co-directed with Maureen Blackwood, the filmmakers mix documentary, monologue and drama to construct an intriguing exploration of Blackness, gender and sexuality in a 1980s Britian that was full of civil unrest. As footage of the streets lined with those protesting for equality and sexual freedom are juxtaposed with images of those who are determined to keep the country predominantly white, the directors incorporate two distinct narratives that centre Blackness within it all. One thread explores Black freedom and the ways it often comes at the expense of Black women, who give all of themselves for the cause, and the other looks at gay men navigating love and homophobia from both the outside world and within their community.

This celebration of gay identity and desire in a hostile society is also found in his captivating film Looking for Langston (1989). Taking a non-linear approach, the film combines archival news footage, poetry excerpts from James Baldwin, Essex Hemphill and Richard Bruce Nugent, and rich black & white cinematography to bring viewers into 1920s’ high society. The result is an absorbing work that is full of passion and desire. It’s one that recontextualizes the significance of the writer Langston Hughes, whose funeral is a recurring motif throughout the film, and the invaluable contributions Black people made to America through the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes was not the only important Black figure on which Julien has reflected. His 2019 ten screen video installation Lessons of the Hour used reenactments, monologues, still photography, and footage of protest to bring Fredrick Douglass’ life into focus and highlights how the fight for Black liberation still reverberates today. Both Julien and Akomfrah have created art installations incorporating documentary elements and poetic imagery in large two and three screen projections that are breathtaking to view while continuing the project of placing Black history into challenging modern contexts.

Black people’s desire to exist free of the burdens and the labels others put on them is one of the themes that can be found in Alice Diop’s filmography. Her award-winning dramatic feature debut Saint Omer (2022) places audiences in the judgmental jury box as they, and the protagonist, observe an immigrant woman who is on trial for murdering her child. A drama that clearly takes its aesthetic influence and approach from her previous award-winning documentary work, the film not only makes one think about the nature of immigrant experience, but also the ways Black women are often tasked with living up to societal norms while suffering in silence.

The isolating nature that comes with attempting to fit into a culture that perpetually views you as the other is prevalent in her 2011 documentary Danton’s Death. The film follows a man named Steve as he attempts to flee the housing projects, where the only options are crime and violence, by training to be an actor. Attempting to keep the two worlds separate, Steve realizes that the predominantly white space of theatre is just as alienating and disenchanting as is his home. Expected to conform and make himself more accessible to his white classmates, he finds it increasingly frustrating that his instructors cannot seem to see past his skin colour. Frequently told that there are no “Black scenes” in many of the classic plays they practice, Steve’s plight feels all to familiar for those whose own desire for reinvention is limited by others who cannot see past the boxes they have been placed in.

Refusing to remain in the structural confines that society expects of them is what makes the works of artists like Steve McQueen, Kahlil Joseph, Mati Diop, John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien and Alice Diop so invigorating. Their metamorphosis across the world of documentary, art installation, and fiction challenges audiences to reflect on the ways transcending traditional notions of space and time can facilitate understanding of Western societies’ fractured and turbulent histories. The haunting truths that are their subjects expose the souls that history has consumed—and, too often, destroyed. It is within these artistic meditations on life that the once blurred outline of Black identity, gender and sexuality come into better focus.