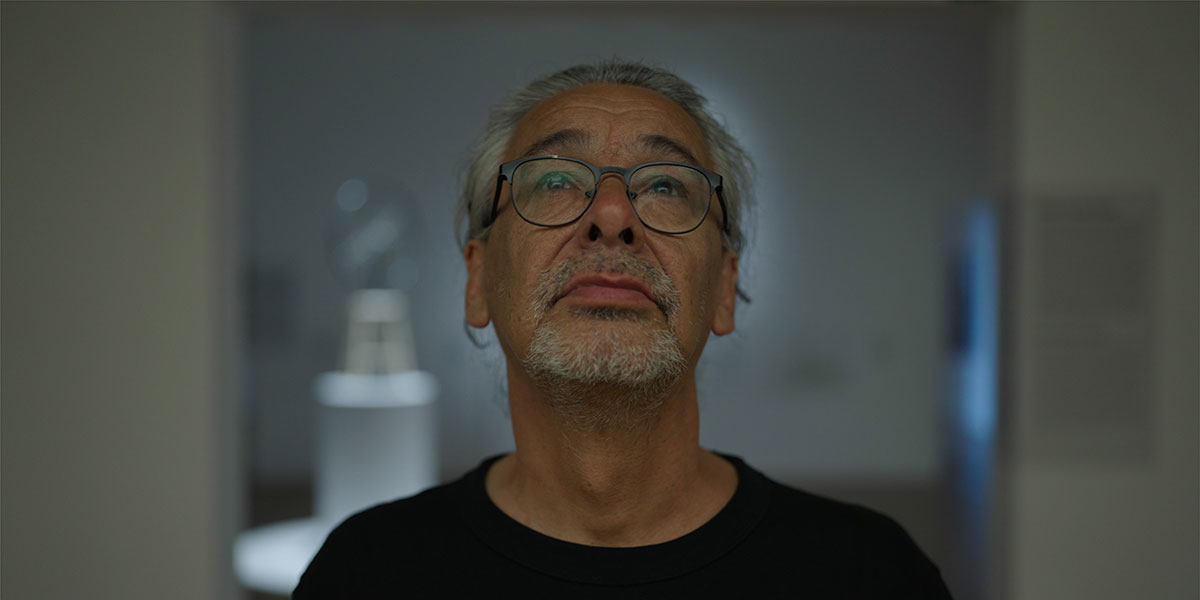

Raoul Peck is one of the most distinguished documentary filmmakers in the world. A former Minister of Culture in his native Haiti, he has lived much of his life in exile, in Berlin, Paris, and the United States. Peck has been making social issue films since the 1970s on subjects as important—and diverse—as the death of Congo leader Patrice Lumumba (Lumumba, Death of a Prophet and Lumumba), the Rwanda genocide (Sometimes in April), the friendship of Marx and Engels (The Young Karl Marx), the barbarous treatment of Blacks during colonialism (Exterminate All the Brutes) and, most famously, the life and art of James Baldwin (I Am Not Your Negro). He has won the Peabody Award, Human Rights Watch’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the Nestor Almendros Prize, and been nominated for an Oscar.

Peck’s new film, Ernest Cole: Lost and Found about the acclaimed South African photographer who exposed apartheid to the world in his brilliant book House of Bondage in the Sixties premiered at Cannes this spring. It had its North American launch at TIFF.

POV editor Marc Glassman spoke with Raoul Peck during the festival.

POV: Marc Glassman

RP: Raoul Peck

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision

POV: Raoul Peck, your films deal with the past. Why?

RP: The past interests me in so far that it allows me to understand and fight in the present. They are tools to help us understand what’s going on in this very complex world. The multiple layers of history interest me because they’re factual, they’re real, and part of who we are.

POV: When did you first find out about Ernest Cole and at what time did you realize that you hadn’t been told the true story of what happened to him after leaving South Africa?

RP: I was in Berlin at the age of 17 in university when I first saw Ernest Cole’s photographs of South Africa. Berlin was a very political city then, the home to all the liberation movements. The ANC, the anti-apartheid movement, was there. We all worked together. I was among the youngest, but I had elders who took me in and educated me politically. Cole’s photos were on the table where we met to make pamphlets and write articles. I was a photographer in those days, so he was part of my world.

POV: When did you decide to make a film about Cole?

RP: Cole’s estate contacted me around six years ago and asked me if I wanted to make a film about him. I was already very deep in making another project, Exterminate All the Brutes, so I told them no, but I could help with the preservation of his photo archive. It was when they were repatriating most of his photo negatives from the Swedish bank. It wasn’t until two years later that I was able to look at all the material and reread about Ernest Cole. I began to see what the film could become.

POV: Was it a surprise to you to realize that the official history of Cole was wrong and that he had continued to make wonderful photographs in the United States?

RP: No, I wasn’t surprised at all. When I started working on I Am not Your Negro, James Baldwin was considered a has-been. My job as a filmmaker is to say, “No, those are people we should respect.” Cole’s work was important, like Baldwin’s—it had changed lives.

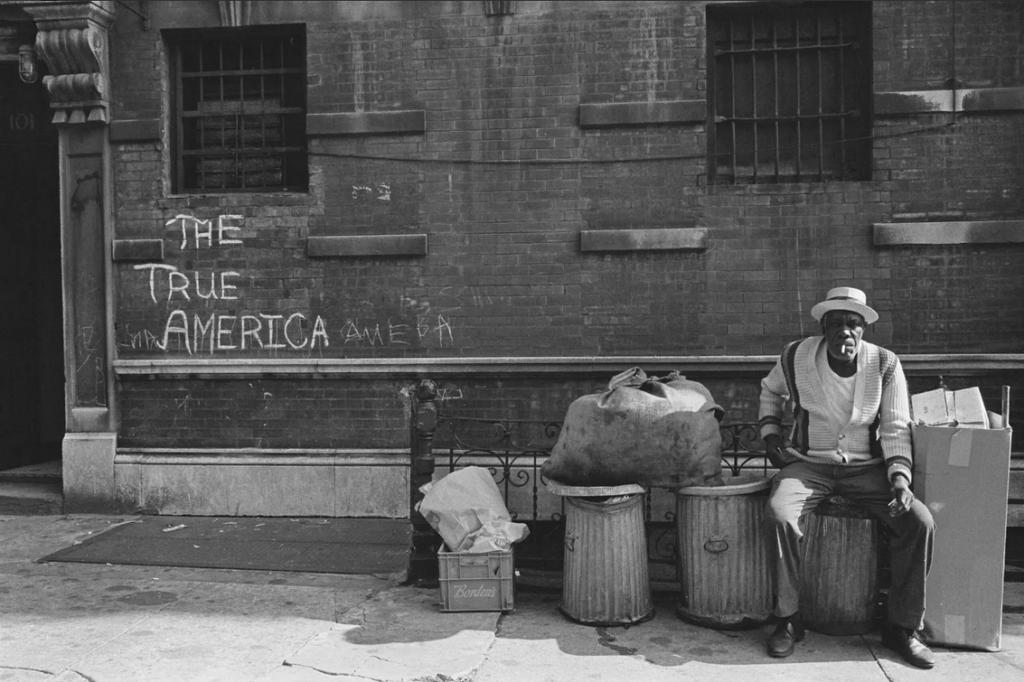

With Ernest Cole, I understood very quickly what he meant and in what sense, his life could have been my life if I had reacted differently in exile. His story is that he became famous by making one big book, House of Bondage, that is iconic. And then he disappeared. He became crazy or paranoiac. Then he became homeless and died. But I knew that wasn’t the true story. It meant nothing. It’s how people talked about black artists then.

POV: What did happen to Ernest Cole?

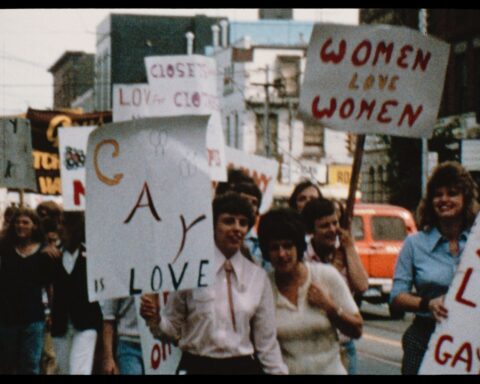

RP: He suffered from being in exile. That’s the centre of it. When he came to America, he didn’t want to be a Black photographer. He wanted to be a photographer. His icon was Cartier-Bresson. Like him, he wanted to go everywhere, to capture stories, faces, situations. That’s the freedom he thought that he deserved. And he didn’t get it. He said, “I don’t want to become a chronicler of misery.” That’s profound. He didn’t want to go to the American South and show tragic people. What happened to Cole takes place with many artists: Black artists, Latino artists, LGBTQ artists, et cetera. They are pigeonholed.

POV: Is that what happened to Cole?

RP: In the Sixties, Black photographers did not truly exist in America. They existed, but they were not recognized. So that was one important part of his life. And the second is that he was in exile. People don’t realize what exile is. Every day, you are living somewhere else, but life continues where you left. You have news from your parents, your friends. People are being killed, being kidnapped, being abducted. That’s your daily life. That was the same for me with Haiti. People think that being in exile is something exotic. No, you are torn in the middle. Those places where you lived are in your head on a daily basis. You are not able to do anything more for your country, for your people, for your family. And that can destroy you.

POV: When I look at Cole’s photographs, even the political ones in South Africa, but especially the ones in America that were so reviled, I see poetry and a love of people. Is that what you see?

RP: Of course. When you are photographing people, your job is to establish a relationship with your subject. You’re not stealing anything. You are trying to establish a type of collaboration. That’s the objective of the camera and the lens. It’s where humanness is transported.

POV: Thinking back to that time in Germany, when you were young, what was your impression when you first met the ANC and got a chance to see Cole’s early iconic photographs from South Africa?

RP: At the time we were very into the fight itself. It was about the result, to end apartheid. It was about everything we could use to do the job. I remember a picture of an older woman in a bank, next to a sign saying, “Whites Only.” I mean, it’s so absurd, it’s almost surrealist. They were important in that sense. There were not many photographers that had the chance to photograph the absurdity of racism or the dictatorship.

POV: What’s your hope now for the film? Will it contribute to a new legacy, a new rereading of Cole?

RP: It has already started. There are a lot of exhibitions going on. Magnum is working with Aperture to show his work. It’s as if someone discovered that The Rolling Stones had 10 albums in a suitcase that nobody knew existed.

POV: There’s a mystery in your film. How come all of Ernest Cole’s photographs were sitting in a bank in Sweden for 40 years?

RP: Well, it is less a mystery than a cover up.

POV: So, there is more to it.

RP: Yes, of course, but I didn’t want it in the film. I didn’t want Ernest’s film to become about how the photos ended up in a bank. It’s Ernest’s time. Let him tell his story. At one point, he says “everything that happened to me is not right.” But what matters is that his work is back where it should be, in South Africa.