Made in Ethiopia

(United States/Ethiopia/Denmark/UK/Canada/Republic of Korea, 91 min)

Dir: Xinyan Yu and Max Duncan

Absolute Concentration. High level of democracy. Reciprocal benefit and mutual benefit. Make progress together. These are just a few of the motivational phrases that loom over the workers of the Eastern Industry Zone in Dukem, a small town near Addis Ababa, which is part of a cooperative region for Chinese investors in Ethiopia. Plastered upon bright red banners, the inspirational texts are intended to motivate the Ethiopians’ work ethic. The Dukem workforce are paid an insufficient monthly salary of $50 USD per month while the landowners continuously exploit the impoverished community. Self-proclaimed as the best-developed industrial park in Ethiopia, the Chinese entrepreneurs mitigate the challenges of bureaucratic negotiation amidst a turbulent political backdrop. A total of 103 companies occupy their factory space, producing cement, ceramics, aluminum, and fast fashion.

In Made in Ethiopia, filmmakers Xinyan Yu and Max Duncan establish a unique portrait of a developing industrial region through the eyes of the workforce and the management of the foreign investors. Three powerful women from different regions are profiled amidst the economic development. An ornate Chinese businesswoman, Motto Ma, an ambitious minimum wage factory worker, “Beti” Ashenafi, and a tenacious farmer, Workinesh Chala, juxtapose perspectives within the Oromia region.

In the opening minutes of their debut feature, Xinyan and Duncan establish the business dynamic between the Ethiopian populace and the Chinese industrialists. The sizzling sounds of lit firecrackers and ceremonious applause signify the commencement of a great wedding between a Chinese businessman and an Ethiopian woman. The seemingly harmonious partying displays the monetary value of the marriage. Stacks of cash are offered to the family of the Ethiopian bride.

In the seemingly disconnected opener, Made in Ethiopia sets the groundwork for its observational lens. An imbalance of money is connected with negligence at the helm of operations during a turning point while the pandemic is raging. Duncan’s intimate cinematography documents a calamitous journey over a time span of four years. Pandemic protocol, a violent civil uprising, and the downfall of a prosperous empire enunciate the selfishness of the corporate world.

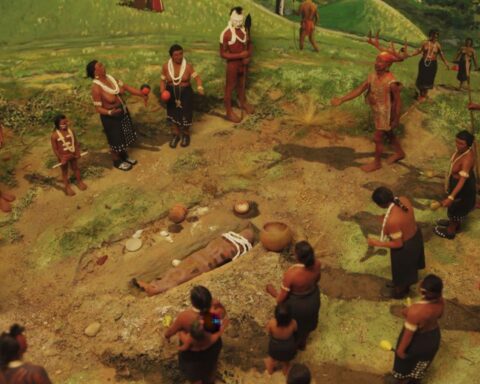

Made in Ethiopia moves at a confident pace, briskly establishing spatial geography with affecting montage. The documentary alternates between different areas of the Ethiopian land, as the camera transports the viewer from the nation’s bustling capital of Addis Ababa to rural Indigenous land. Along with the consistent location switches, the film attempts to provide an objective perspective on the evolving conflicts taking place. Town Hall congregations, business delegations, and acts of protest are admirably featured with respect and tolerance. The film avoids any form of active participation within the developing narrative, as the globalization of Ethiopian commerce challenges the country’s democratic relationships. Some may suggest that the documentary is Ethiopia’s answer to American Factory (2019) as both films demonstrate commercialized culture clash with boastful empathy.

However, despite its objective authorship, Made in Ethiopia neglects various elephants in the room. As the film reaches its inevitable climax, Made in Ethiopia skips past the nation’s political discourse—particularly the Tigray war—in favour of digestible commentary. The depiction is questionable at best since the lives of the subjects are compromised due to a rise of sexual violence against women as a systemic war-mongering tactic. The film deviates from the uglier truths of the Ethiopian struggle primarily shooting away from the communal distress of the civilian workforce. Xinyan and Duncan appear to empathize with the Chinese business owners like Motto Ma. Tough questions regarding the mental and physical health of the workers are discarded for a plethora of senseless business-pandering scenes. The philanthropic veneer adopted by the Chinese continuously reiterates the extensive financial losses of the business structure, instead of prioritizing a humanitarian perspective.

The directors adopt a passive social-political approach, presenting both sides of the conflict with a false balance of interests between the corporate zeitgeist and the preservation of Indigenous traditions. The apathetic “humanitarian” pursuits in the Eastern Industrial Zone only unveil a fabricated publicity exercise. The presence of Duncan’s camera is an undeniable influence on the industrial subjects weaponising the presence of the camera as a tool to promote their self-image. The dialogue of the industrial subjects repeats itself with little deviation nor nuance. In contrast, the Indigenous perspective prevails through genuine conversation conducting thoughtful debate regarding the customs and traditions of the land.

Made in Ethiopia is complicit in a different kind of war, a battle between the seen and the unseen. The prosperous workforce is the lifeblood of both the Eastern Industrial Zone and the emotional crux of the documentary. Emphasis on statistics merely distracts from the apathy of the capitalist infrastructure, swerving through the timeline with a hefty bias towards the upper class. The film raises more questions than answers regarding China’s aggressive courtship of Ethiopia, as the country’s toothless national structure merely scratches the surface of the corporate rhetoric.