Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues

(USA, 104 min.)

Dir. Sacha Jenkins

Programme: TIFF Docs (World Premiere – opening night)

In taking on a subject as vast and influential as Louis Armstrong, the pioneering trumpeter whose decades-long career helped define the genre of improvisational music with which he’s practically synonymous, it would be easy to expect a multi-hour mini-series. In fact, we’ve gotten that several times before, with Ken Burns’ Jazz practically a paean to Armstrong, thanks in no small part to the influence of Wynton Marsalis in helping craft the narrative of that vast project around “Pop’s” own journey.

It’s a testament, then, to Sacha Jenkins for not only carving out his own space to commemorate Armstrong’s legacy, but to also do so with a highly specific audience in mind. Louis Armstrong’s Black &Blues reminds young people, especially African Americans, what a titanic talent Armstrong truly was, while contextualizing many complicated elements of his performances and behaviours that require perspective to understand fully.

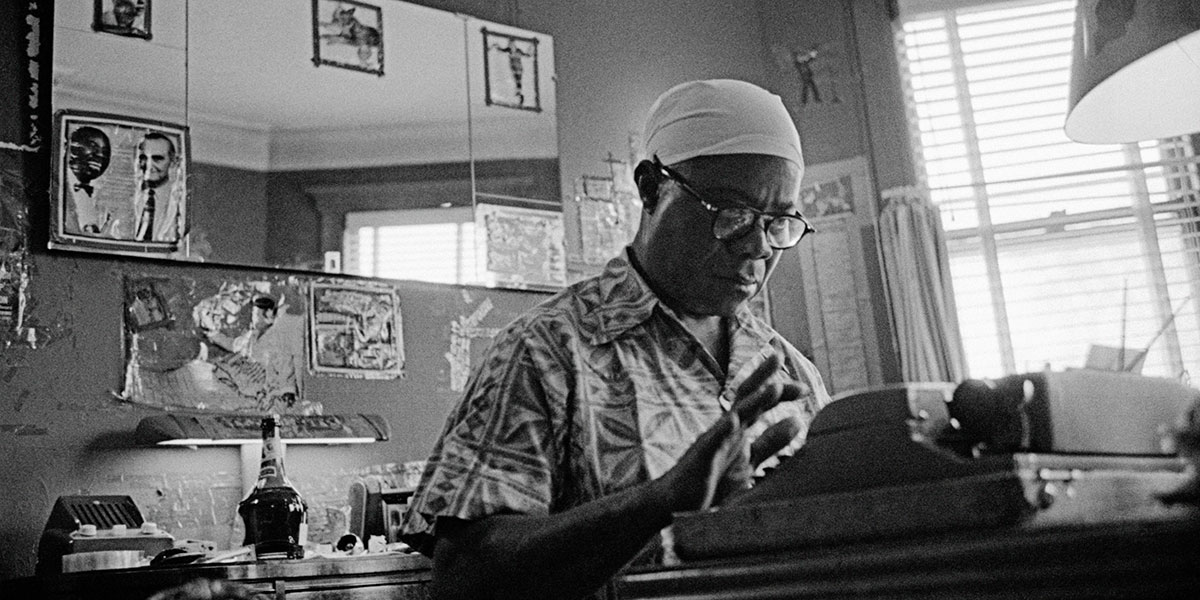

It is therefore in no small part that Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues plays a pedagogical tune as much as a commemorative role, using for the first time Armstrong’s own voice to help tell his tale. By employing home recordings of conversations, interspersed with some of his more famous compositions and appearances, one gets a sense not only of the artist but of a complicated man of his time, fighting in his own ways for justice but equally illustrating to generations of musicians with whom he collaborated or influenced the power of his horn.

As such, it’s no small thing to firmly establish Armstrong as not only one of the truly iconic voices of the 20th century, but to do so while encouraging those who are used to the smiley face, bug-eyed stereotype to look beyond and see what’s both at play and at stake. For musicians, or fans of jazz in general, the revelatory moments are those private, intimate ones showcased through use of animation and collage, mirroring Armstrong’s fascination with keeping his clipping in vast scrapbooks.

In fact, this magpie tendency helps explain musically the power of Armstrong’s gift, how in a disparate community like New Orleans, the key to this new music was an amalgamation of cultures from polka to martial music to West African rhythms, steeped into a gumbo and flavoured not through rote repetition but with the magic ingredient of improvisation. Before the bop players broke down ii-V changes with metrical calisthenics, and well before Miles Davis and company made modal lines the new post-cool, Armstrong and his contemporaries provided lyrical lines and exultant flourishes, mixed with sombre compositions echoing the pain and suffering of their people. This was Black music filled with the blues, but even at times of the most misery, there was never silence. There was always time for the cry of the horn.

For whatever viewers may have never heard a note of Armstrong’s before, there’s enough of a historical throughline to provide context and examples of his talent to draw one into his world. By using voices such as Nas to speak to a crowd weened on sampling and rhymes rather than choruses and solos, there’s a welcome, even earnest attempt to bridge the contemporary with the past.

The result is effective if slightly defensive. It’s no small challenge to convince those closed off to the importance of this history to embrace something that’s hardly unique to this project. What may set it apart is the inclusion of a number of voices that admit their own initial struggles in looking beyond the iconography of the man and their own prejudices about his role in the development of American culture, especially when raised on those who proceeded the legendary horn player. Hearing from Miles speak rhapsodically about Armstrong is helpful, but so are people raised decades after Armstrong’s passing, who show how he’s not simply a historical anomaly but an integral part of musical legacy.

Marsalis himself has spoken often about his journey to appreciate Armstrong, while now he habitually refers to the man as the “Bach” of jazz. It’s a good analogy, especially for those conversant on European orchestral music, but the difference, of course, is that for literally centuries, Bach’s own legacy faltered, only resuscitated with active advocacy by those who recognized his genius and worked hard to ensure its impact wouldn’t be allowed to falter any longer. For those versed in the history of jazz, this seems an impossibility, yet as young people find their own music the icons of the past become more and more distant, and seen through contemporary lenses, much of what Armstrong appears to represent is thought of in a negative light.

As such, Jenkins’ film plays a pivotal role in reaching out not only to this generation but to future ones, peeling back the layers of the man and showing better than any previous documentary has the fundamental power of the man and his music through his own voice. The end result is an entertaining and informative film for even the most jaded of Jazz fans, but equally a powerful and pedagogically rich testament to the legendary man.

For the first time on film Armstrong is allowed to toot his own horn, as it were, allowing his ideas as much as his music to flourish. Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues is the portrait of a man, an African American, a teacher, a husband, a father, a bandleader and more, someone who both popularized a music but also provided harmonic complexity and astonishing, athletic prowess on his instrument that helped write the very rules of the artform. Whatever came before or since, they’re all seen through the lens of Armstrong’s long life. Thanks to what’s illuminated throughout this documentary, that legacy will continue to ring out for years to come.

Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues premiered at TIFF 2022 and debuts on AppleTV+ later this year.