Free Money

(Kenya/USA, 74 min.)

Dir. Sam Soko and Lauren DeFilippo.

Programme: TIFF Docs (World Premiere)

Whatever the economic pros and cons of a universal basic income (UBI) are, the idea is tremendously appealing because it respects the dignity and personal agency of recipients of aid. End extreme poverty by giving people money; then watch how their health, education and economic power improves. The documentary, Free Money, which had its world premiere at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, follows a social-economic experiment in universal basic income to a village in Kenya, conducted by a non-front aid group, GiveDirectly, the brainchild of Harvard-educated economist Mathew Faye.

Faye’s insight was that money could be sent directly to people’s accounts via mobile phone transfers with minimal cost, breaking the cumbersome chain of politics and logistics in delivering aid to poor countries. After winning a 2012 award of more than $2-million backing from Google, he was able to start the economic experiment which the film chronicles. Faye, who, in television interviews comes across as upbeat and hopeful, follows the template of the tech visionary: He’s non-ideological, dedicated to “disrupting” conventional ways of doing things through technical solutions. Other fans of UBI include Elon Musk and former Democrat presidential candidate, Andrew Yang, who we see interviewing Faye in the film. And, on the face of it, his solution is exemplary. GiveDirectly is highly rated for transparency and efficiency, and, partly influenced by the success of COVID-19 economic bailouts, the basic income model has grown in popularity in many countries.

Filmmakers Lauren DeFilippo and Sam Soko’s concise and balanced documentary, Free Money, isn’t intended to be adversarial to basic income concept; it’s more about giving the idea, and especially its implementation, a sober second thought. More broadly, the film is a reflection on the unintended consequences of good intentions, especially when it involves rich people in Western countries deciding what’s good for poor African people

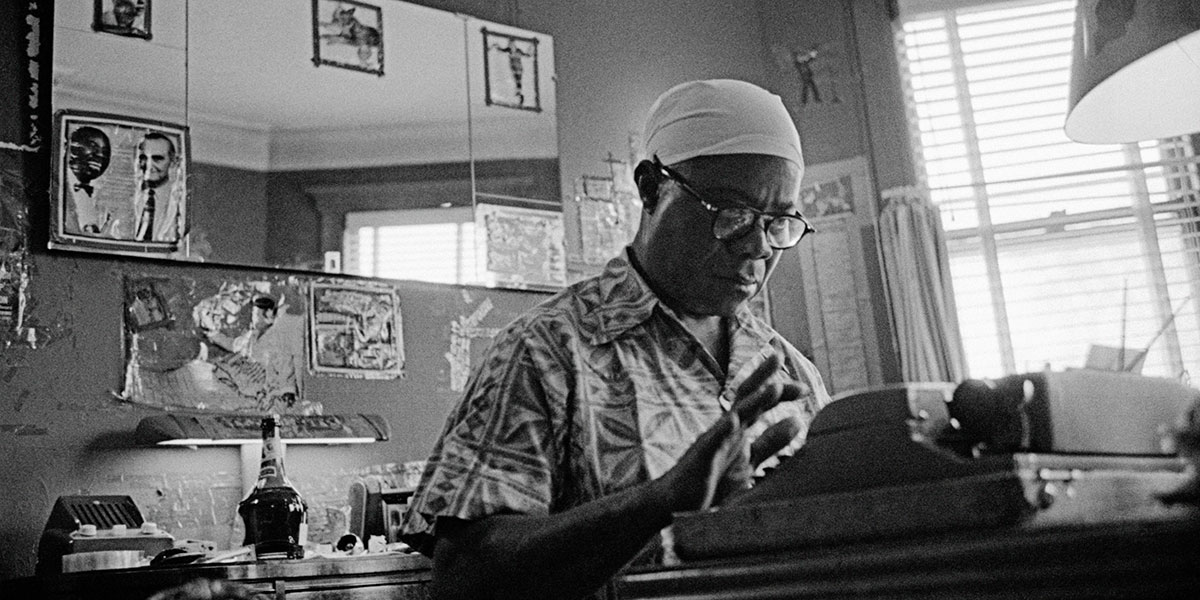

There’s a key number in the documentary: $22. That’s the monthly stipend provided by GiveDirectly to everyone over 18 in the Kenyan village of Kugutu. The monthly deposit will continue for 12 years, the length of a study to see how the money can lift people out of extreme poverty. The film began when American director/producer, DeFilippo (Red Heaven, Ailey) decided to follow what happened to recipients of the Kenyans who received the magic $22. She reached out to Nairobi-based filmmaker Soko, director of the internationally successful 2020 documentary, Softie, a portrait of photojournalist and activist Boniface “Softie” Mwangi, which was bought by both PBS’s POV and BBC’s Storyville.

Set among the red dirt roads through bright green foliage, simple one-story houses and streets filled with goats, chickens and motor scooters, the film puts us in the world of the people who are subjects of the experiment. Initially, some of the villagers are skeptical. Someone says they heard the money comes from the Illuminati. Some men are concerned their wives will become too independent with their own money. But most embrace the idea of $22 a month as a life-changing opportunity. Even the local clergyman endorses the plan, with the recommendation that the congregation pass on some of their bonanza to the collection plate.

When the filmmakers visit the recipients after they’ve received their first installment, excitement is running high. For 18-year-old John Omondi, who wants to go to school, the $22 will “cover my basic costs, transportation to school, some of my school fees and other things.” One woman has a well dug near her house, freeing her from hauling water. Another buys livestock, while yet another fixes her roof.

Yet, early on, flaws in the plan become apparent. One young woman, Jael Rael Achieng Songam, yearns to follow her dreams of getting a higher education, but she’s shut out, apparently because of a clerical error, and over the four years of the film’s shooting, we see her grow progressively disheartened. We hear from other Kenyans that the money has split the community into haves and have-nots: Those who have cash go to the head of the line at the local market. Neighbouring villages admit their jealousy of Kugutu’s unearned bonanza; some even questioning whether they have been abandoned by God.

Then there’s the issue of the 12-year timeframe of program. Parents, looking ahead, can see that their first-graders will enjoy the full education, but their babies won’t. In year four, comes an external event that warps the entire experiment: The COVID pandemic. Because people cannot work, kids are withdrawn from school and the $22 has to be used for basic living. Something not counted on in the experiment’s design was that catastrophes have a disproportionate effect on the poor.

One key issue is that the experiment seems designed to make people dependent on a system over which they have no control. The most intriguing development in the beginning was a “savings circle,” intended to pool a portion of each villager’s income to help out their neighbours when extraordinary needs arise.

One persistently skeptical voice in the film is CNN journalist, Larry Madowo, who grew up in a similar Kenyan village to Kugutu,. In an interview, Madowo forcibly challenges Faye on the hubris of his plan, on the ethics of treating people like guinea pigs and the long history of non-government organizations wreaking “havoc” with people’s lives. Faye is taken aback; he responds that he “hates” the word “experiment,” though he also prides himself on his evidence-based approach. You can’t help feeling sorry for him because, of course, his intentions are so obviously good.