“To search for the good and make it matter: that is the real challenge for the artist. Not simply to transform ideas of revelations into matter, but to make those revelations actually matter.” – Estella Conwill Mojozo

You might not expect The Take, the brave new documentary by journalists and political activists Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein, to be a love letter, but it is— a deeply felt and sincerely composed one to their fellow compañeros. While the film is a lucid critique of capitalism’s myriad wrongdoings and deals with complicated socio-economic and political issues, which under the name of globalization have radicalized millions around the world, it is primarily a message of hope. What makes it riveting is that it brings to light profoundly human stories that transcend the clichés of globalization. Lewis and Klein have given this complex reality a human face: people fighting for their right to work in financially devastated Argentina.

The relationship of art to social change has a long and varied history. As the renowned theorist Herbert Marcuse recognized, the possibility of human liberation lies in our belief in the imagination. Picasso painted Guernica in reaction to the Spanish Civil War; the Brazilian martial art capoeira was originally cloaked as dance during slavery times in the 17th century; in the ’60s, musicians wrote popular songs protesting the Vietnam War. These days, agit-prop art is more media savvy than ever. Political documentaries are exploding, mirroring a collective urgency to dig deeper into the truth, past cynicism and indifference.

Avi Lewis, the film’s director and co-producer, has years of experience in the media. In the mid-’90s, he hosted a hip, informative TV show called The New Music, and often found ways to infuse politics into the stories. He went on to host a national, primetime talk show, counterSpin, moderating over 500 political debates in three years. Now, he’s put himself on the other side of the camera, adding a new dimension to his activism. “There’s a distance and scrutiny that’s introduced when you look at a phenomenon through the lens of a camera,” he comments. “Zooming in and figuring out how to piece together a story in filmic terms allowed me to see from a different kind of perspective.”

Naomi Klein, The Take’s writer and co-producer, is the author of No Logo: Taking Aim at Brand Bullies, an acclaimed bestseller that has been translated into 27 languages. She’s a regular contributor to such influential publications as The Nation, The Guardian and The New York Times. Even during The Take’s lengthy shoot, she continued writing—16 columns in 8 months—which amazed Lewis. “The war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq both happened while we were in Argentina, so Naomi never left that track of her work. I frankly don’t know how she does it.”

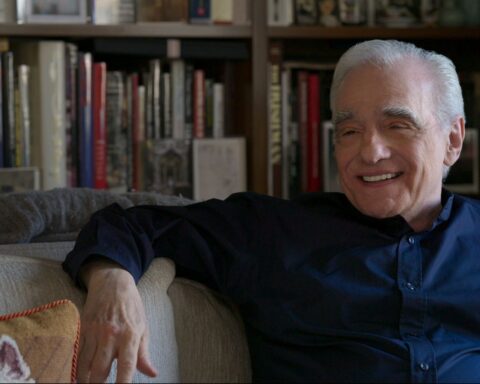

Toronto is their home base. Klein and Lewis live in an ethnically diverse, downtown neighborhood, across from an elementary school, close to markets and a community centre. A classic Toronto Victorian on the outside, a think-tank in the inside. Their assistant greets me and offers some green tea while I peruse their extensive bookshelves—lots of world literature, cultural theory and philosophy. Propped against a wall is a painting of the film’s poster, a gift from their international sales agent, Celluloid Dreams. The house feels uncluttered, fine for clear thinking.

I had met Avi Lewis earlier in the year just before their film’s world premiere at Hot Docs. What struck me about him then, and now as he enters the room, is Lewis’ great enthusiasm—he’s full of facts and information—while his manner is warm and easy-going. Naomi, he tells me, will join us soon; she’s smack dab in the middle of breaking a major story for the U.S. press concerning dark secrets and shady dealings of former Secretary of State James Baker. One can only imagine what the breakfast conversations are like around here.

The Take is being released at a time when documentaries have become wildly popular in the mainstream, yet funding and making them in Canada remains an uphill challenge. From government cuts to record numbers of emerging filmmakers all vying for the same, small slice of the production pie, the times they aren’t yet a-changin’. Lewis spent a year convincing the NFB and CBC that Canadians would care about the film. “I’ll confess that I thought it was going to be easy for us because we both occupy fairly prominent places in the media world,” comments Lewis. But, “we went through the whole process that everybody goes through—various stages of interrogation and inquisitions. I was treated like a first-time filmmaker over and over again and that wasn’t fun.” Rounding out the financing was Toronto- based Barna-Alper Productions.

Naomi Klein appears, cell phone in hand, and joins us at the large harvest table in their dining room. She’s gracious, even a touch shy. I’m curious about their motivation in putting themselves into the film, both on camera and as narrators, because, for me, it upped the emotional ante. “When a filmmaker is narrating a film, I want to know a little bit about where they’re coming from,” Klein explains. “Trying to be an absent, neutral narrator would have felt more dishonest than to say, ‘Look, this is who we are, this is where we come from, this is what brought us here. We feel this is the next stage of the globalization discussion and it’s an answer to the question we’ve posed, so check it out.’”

As a genre, point-of-view documentaries allow Canadian directors to make films in other countries and still fulfill the Canadian content requirements. “There are a lot of routes to the goal,” comments Lewis. “And I think we needed to go somewhere else and find a place in the world where something really exciting was happening and bring that excitement home.” In response to what they call ‘the new impatience,’ activists seeking out positive alternatives, Lewis and Klein traveled to Argentina following rumors of an emerging worker co-op movement. This was not armchair activism—they moved down there for 8 months and immersed themselves in the upheaval.

“This is Argentina, but it could be anywhere. A rich country made poor. Welcome to the globalized ghost town.” So begins The Take. In the early ’90s, Argentina appeared to be a poster child of progress and economic growth, but festering beneath all that shiny foreign investment was a crumbling system fed on corruption and greed. By 1999, it had all collapsed, throwing the county into anarchy and despair.

In The Take, we meet people from three factories who have risen up, taking power into their own hands. They represent different facets of the country’s struggle for renewal. Brukman’s suit factory was the first operation to be occupied, taken over by its seamstresses; it has since become the “beloved symbol of Argentina’s new politics.” Brukman’s is an “activist mecca” where meetings take place during the day around sewing machines, and at night, there are concerts outside the factory’s gates. One woman sums it up with troubling irony: “For us as workers, accounting is easy. I don’t know why it’s so hard for the bosses to pay salaries, buy materials and pay the bills—you add and subtract.”

We meet Maty, a new co-op member at the Zanon ceramic tile factory, which has been under worker control for the past few years. She is young, in her 20s, and represents the movement’s next generation. Zanon is rooted in the community on many levels: donating tiles to neighboring hospitals and schools. Popular rock bands have written songs in support of Zanon.

If there’s a protagonist in the film, an unsuspecting hero, it would have to be Freddy, a factory worker and family man. When his Forja auto-parts plant shuts down, he and his co-workers band together, and decide to organize. Forja is the new kid on the block—Brukman and Zanon have turned before—and it is through Freddy that we have the opportunity to witness the step-by-step process by which a movement is born. We see council meetings and community networking sessions, demonstrations in the streets, and intimate family gatherings where financial concerns are part of the daily conversation. These sequences are eerily juxtaposed with the upcoming presidential election and short-lived resurrection of Carlos Menem, the former President of Argentina, who brought the country into prosperity and then poverty in the ’90s.

While in Buenos Aires, Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis lived collectively in a group of nine. She explains that, “it was an adventure we were all on together. An experiment and a moment of people living in Argentina because we believed in what people were trying to do there, and we wanted to be a part of it and we wanted to learn from it.” As a group, Lewis and Klein and the others would brainstorm about how to illustrate ideas in the film: for instance, a whole day was spent on critiquing the IMF (International Monetary Fund). They also watched political documentaries together, like Life and Debt and The Revolution Will Not be Televised, and discussed what worked and what didn’t. “Not everybody brought the same politics to the project,” says Lewis. “Some of the people had really strong feelings about consensual decision-making and horizontal organizing. Of course these are themes in the film, but it (the directing process) was not a democracy. Ideologically they had a really good point but, practically, I was the director.” As first-time filmmakers, Lewis and Klein were learning on the job, just like Freddy and the boys at the Forja.

One of the most poignant sequences in the film occurs when the workers and their families celebrate their legislative victory against the Forja’s owner with a fiesta. While Freddy, endearingly off-key, attempts to sing a popular Mercedes Sosa song, we see Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein sharing a quiet moment. Then the scene shifts, and Sosa’s hauntingly beautiful voice is heard over images of a brutal confrontation with police outside the Brukman factory. That Brukman could once again be vulnerable underscores how tenuous the movement is, and yet how vital it is to carry on: “Who said that all is lost? I come to offer my heart—it won’t be easy, but it will pass. It won’t be as simple as I first thought, like opening one’s chest and pulling out one’s soul, like a stab of love.”

Making a film like The Take requires a kind of emotional stamina, and I can’t help but wonder how Lewis and Klein stay committed. Avi Lewis admits that’s “a deep and impossible question to answer. It’s a matter of identity. For better or worse, Naomi and I are both political animals and policy wonks. The excitement in this household when a 75-page deal memo comes in that implicated the Carlyle Group and the Albright Group about a huge conflict of interest around the selling of debt between Iraq and Kuwait—it was electric around here.”

For most people, it’s all too easy to distance themselves from what is—to deny that harsh realities might be careening faster and faster toward home plate. In South Africa there’s a word, ubuuntu, which poetically describes the very essence of being human: knowing that a person is a person through other persons, that we are interconnected and that we belong to one another. “What could be more global,” suggests Lewis, “than a couple of Canadians going down to these post-industrial neighborhoods in Argentina and seeing the seeds of their own possible future?” For him, The Take is about “the future of our (Klein’s and Lewis’) activism and a cautionary tale of where our own country is headed if we keep going down this particular economic path.”

Speaking of The Take and both her work and Avi’s, Naomi Klein comments: “Give people ideas, that’s all we can do.” There’s an irrefutable unity between who Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein are as people, as activists, and as filmmakers. “As an activist who is fundamentally driven by politics and rage against the machine, and love and admiration for people who resist in creative and constructive ways,” states Lewis, “all I can do is keep prying myself open at each stage to figure out what I can actually learn from any one experience that will inform the next creative decision.” The circularity of Avi Lewis’s comment is fascinating—it’s an amalgam of their lives, and mirrors each stage of their creative process. Learning as they go, discovering what is needed, and always moving forward.

Taking The Take to Festivals & Co-ops

The Take has screened at many festivals, activist gatherings and worker co-ops around the world, and the reactions have been strong—both politically and emotionally. At the opening night of DOXA, Vancouver’s documentary film and video festival, people are swarming the entrance of a downtown theatre. Unlike most Canadian cities, “green” politics are more integrated into daily life here, and the energy is buzzing. Several local politicians are on hand to introduce the film and they’re greeted with rounds of applause, as are Lewis and Klein.

The audience seems to act collectively, bracing itself during emotionally-charged moments when human dignity butts up against police hostility. There are boos and hisses right on cue when the smug owner of Zanon is interviewed, or when Menem appears, oozing insincerity and self-interest. Everyone cheers when the Forja workers triumph in their court case and are allowed to re-open the plant themselves. After a rowdy standing ovation, questions and comments fly from all around: people want to engage, communicate, and share. As they spill out of the theatre, emotions are running high; the crowd is both energized and activated. Avi Lewis tells me this happens after every screening.

This past summer, The Canadian Worker Co-op Federation expressed interest in screening _The Take_ at their annual meeting in Moncton, New Brunswick, where members from around the country congregate. It’s a great idea because, as Lewis says, “a film can travel places where a union organizer can’t.” What they’re noticing is that, while worker co-ops in Canada have been around since the early ’60s, there’s resurgence happening for exactly the same reasons as in Argentina, but playing out in very different ways. Here, the economy is still resource-based. There are logging, pulp and paper, and fish canning co-ops springing up all over the country in environmentally sustainable, community-centric ways. Groups “are incredibly excited about what the film is going to bring in terms of the co-op model in the Canadian public imagination. And it’s right here in our backyard.”

An Activist Film Release

From the years Naomi Klein spent promoting No Logo, she learned a lot about what not to do when releasing a cultural product. Being in a different place every day left her drained and exhausted, with no time to learn about the communities she was in. “We’re not asking local activists just to sell our film,” she points out, “we’re also supporting the work they’re doing, as well as supporting the audience that comes out. The first thing they want to know is, ‘What can I do?’ And there are groups right there for them to connect with.” This reflects the essence of their parallel distribution strategy.

Lewis and Klein have attracted Canada’s largest distributor, Odeon, who signed onto the idea of having activist fundraisers in every city a few of days before the film opens. “We’re using the film as a launching point for discussion with all the frontline activists we can reach, about how they can apply (the ideas in _The Take_) in their own struggle,” explains Lewis. And since a strong opening weekend is crucial to a film’s shelf-life, they hope to build momentum through word of mouth: appealing to their core audience, people already invested in the subject matter, who will spark interest in the mainstream, multiplex audience.

The grassroots promotional campaign was developed with Good Company, who successfully marketed another important Canadian political documentary, The Corporation. Like that film, a “website”:http://www.nfb.ca/thetake/ has been developed which is a hub for activist movements. The site is definitely worth the trip.

For Klein, “It’s a nice moment of uncertainty in the film industry that’s allowed for a little bit of oxygen. People are not totally set on a pattern that has to be followed and that’s allowing us to say, ‘Here’s a different recipe, let’s try it.’ And hey, the Carlyle Group hasn’t bought all the theatres in Canada yet!”