Hollywood often looks to documentaries for inspiration, but a documentary getting the scripted treatment in Canada remains rare. However, the acclaimed 2017 documentary Birth of a Family offers just the right ingredients for a dramatic adaption. Filmmaker Tasha Hubbard returns to the story with Meadowlarks, a drama about four siblings uniting after the Sixties Scoop tore their family apart. Both films offer unique and moving accounts as the siblings meet in Banff to enjoy the family they never really had. Their tale evokes the effects of the child removal system with personal stories about the impact on families that carries through generations after Indigenous kids were lifted from their homes and transplanted into white families.

“I really love Birth of a Family,” Hubbard tells POV over Zoom. “It was my first feature. It was the first time I really tried to really lean into more observational storytelling and it just lived in the world.”

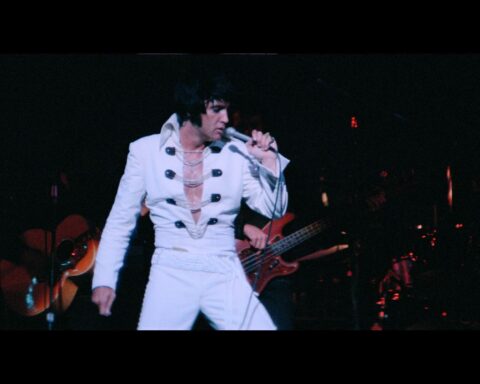

Birth of a Family, Tasha Hubbard, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Hubbard says that when Birth of a Family premiered at Hot Docs, where it finished in the top ten for the audience award, producer Julia Rosenberg approached her to see if she ever considered it for a scripted project. The director says she saw an opportunity to explore aspects of the story she couldn’t quite pursue in Birth of a Family. “The original family had some boundaries and I respected fully what they wanted to share and not share,” she explains. “I said, ‘We can just make [the documentary] about this moment in time.”

While Birth of a Family follows Betty Ann Adam and her siblings Esther, Rosalie, and Ben as they meet in Banff, Meadowlarks tells the story of a fictional family with Connie (Carmen Moore) organizing the trip with Anthony (Michael Greyeyes), Marianne (Alex Rice), and Gwen (Michelle Thrush). The four siblings share stories about the respective families they were adopted into and the new ones they’ve since created on their own. Hubbard says that scripting a family allowed her to explore aspects of her own experience along with additional perspectives from people she’s encountered over the years.

“I could really lean into some of the other stories that I’ve been told, or that I knew of,” says Hubbard. “I won’t say that none of the characters is me, but just different experiences or ideas or thoughts that I had did find their way in.”

The director previously explored the complexity of her own family story in the 2019 documentary nîpamistawâsowin: We Will Stand Up, which included pivotal conversations with her white family members about what it means to raise a Cree child in Canada, where young Indigenous people still experience the lateral violence of colonialism.

“I’d gone through the experience myself of meeting my family, I was 16—not quite an adult, although I thought I was—but meeting them at an older age, I’d met others who’d gone through the child removal system,” says Hubbard, who was adopted out of her Cree birth family at the end of the Sixties Scoop. “There are different stories, and I thought I could tell this story from that fictional space and be, in a way, more representative. Birth of a Family is one family story. It doesn’t stand in for everything.”

As with Birth of a Family, Meadowlarks doesn’t get into the full history of the Sixties Scoop, nor does it have to. Instead, it captures the collective healing of these four individuals as they find closure that’s long eluded them as the union with lost siblings inspires further connections with their culture and language, which some of the siblings relate to more than others. The film also adds a fifth sibling who opts out of the getaway and his absence lingers throughout the trip. He’s a symbolic presence for all the people who aren’t as lucky in the healing process.

“These characters, even though they should have had the same upbringing with the same parents and shared experiences and memories, they don’t,” says Hubbard. “What they’ve gone through has been tough. And then what does that mean for them? What patterns do they have that are going to make it challenging to form this bond in such a short period of time?”

As the film explores the challenges that the four siblings have in forging these bonds, Hubbard seems to find particular interest in Anthony. The brother reckons with the weight he carries as the elder sibling. He seeks forgiveness for not protecting his sisters, while they inspire him to see that a child was not at fault for the family being ripped apart by the state. Anthony’s depth, brokenness, and efforts to heal are among the elements that clearly set the drama and the doc apart.

“I chose not to look at the documentary until halfway through the filmmaking,” explains Greyeyes. “I didn’t want any characters in the documentary to unduly influence how I approached Anthony because Anthony is an entirely fictional creation. But there were some parallels or echoes that I thought were really important.”

Moreover, Greyeyes says that Anthony represented a chance to break free from typecasting, as he’s generally known for playing tougher characters. For example, he recently appeared as the gun-totin’ father protecting his family from strange invaders in the dystopian actioner 40 Acres, directed by R.T. Thorne, and won a Canadian Screen Award for his heroic lead in Jeff Barnaby’s zombie bloodbath Blood Quantum.

“I’ve played a lot of characters that were hard and tough badasses. Anthony’s not a badass,” says Greyeyes. “There was this beautiful fragility to him. I think that’s a really important story to tell when you look at some of the work that I’ve done, a project like Wild Indian, which a friend described as a portrait of how Indian men hold their pain. This is a different story. This is a story about how emotional growth can sometimes get interrupted or corrupted by our experiences. I looked at Anthony as a person who had this boundless kind of love and hopefulness, but his ability to express it or to even feel it was compromised.”

Greyeyes says he explored Anthony’s brokenness by using his trademark height against the character. Instead of striding confidently, Anthony carries himself like a little boy. One sees this dynamic when Anthony goes for morning strolls with Marianne, an avid runner whose life in Belgium inspires a metropolitan poise to her gait.

As the siblings roam through Banff, they each experience transformative moments, like Connie overcoming her fear of heights atop a suspension bridge. Anthony, meanwhile, recognizes that his future grandchild will allow him to be something he never had—a grandparent. His walks and, eventually, jogs with Marianne convey how his discomfort with his own body and his sense of being ill-at-ease gradually melts and he strides confidently by the end of the trip.

“It’s over the course of the weekend, and over the course of being in contact with his sisters and his family, he was finally able to stitch together an understanding of these emotional bits,” observes Greyeyes. “And then as soon as he came together, it was like he started to heal. I think that’s an important story to tell in cinema because we don’t have a lot of films written with that kind of perspective for Native men. We’re just badasses.”

The relationship between Anthony and Marianne is one example of the narrative structure in Meadowlarks that sees siblings pair off during the weekend. Anthony experiences growth with Connie and Gwen as well, and the sisters frequently pair off in turn. These interactions outside the fuller family gathering illustrate how the siblings feel their way into their newly united family.

Hubbard says that it was important for her and co-writer Emil Sher that the quartet of siblings wasn’t always together. The filmmaker says those pairings reflect a dynamic that would have existed had the family not been torn apart. “They would’ve had these individual and different relationships, so we wanted to see that form,” notes Hubbard. “It really was so character-driven in what those look like. But they’re all coming from different experiences as well that have shaped them. I’m always interested in what people’s true original nature is, and then what happens when, because of colonialism, they’re altered in some way, or as Michael pointed, stunted in some way or shaped in a different direction. I wanted the characters, over the course of the weekend, to become who they’re meant to be.”

“An important part of the overall idea of how we play with each other is that families, the colonial story, the historical part of the film that’s already being told, is almost unspoken,” adds Greyeyes. “Our job as actors is to be inside the family and the family dynamic. So, of course, some brothers you don’t like and some brothers are your best friend. I think that just happened during the course of the story. For Anthony, his relationship with some of the sisters of introductory, but almost immediately he and Marianne connected.”

Having the siblings branch off also leads to an extremely powerful union in Meadowlarks’ final act as they share a new experience. Marianne meets an elder while browsing Indigenous arts booths at a market and the woman, sympathetic to her story, invites her to bring her siblings for a healing ceremony in the woods. While the siblings in the documentary do meet an elder at the cultural centre in Banff, the scene with the ceremony is unique to Meadowlarks. There’s collective catharsis as they let go of their shared pain.

“When people have gone through the child removal system, sometimes there’s challenges coming back,” Hubbard says on finding her inspiration for that scene. “There’s family dynamics or people have passed already or there’s terrible circumstances. Sometimes it’s not possible for people to find their families.”

Hubbard reflects on the story of one of her friends from Saskatchewan who was struggling to connect with his birth family. Amid his search, he went to his family reserve one weekend for a powwow. While he didn’t quite find the original people he was looking for, another family adopted him. “They did this beautiful welcome, and I always thought about that,” says Hubbard. “I wanted something like that. These elders are not their relatives and it doesn’t matter because the compassion and love is there. I’ve heard other stories similar to that. It’s their coming home moment and they’re coming home to each other. The elders fundamentally understand that. Now they have that centre.”