“When somebody that you love becomes a mythological figure, it colours everyone’s version of [them],” filmmaker Amy Berg observes.

In life and in death, singer Jeff Buckley, the subject of Berg’s latest film It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, represented many things to many people. With the release of his lone studio album Grace in 1994, he captured youthful hearts with his deeply romantic lyrics, offering a tender alternative to the grunge of the day. (“My kingdom for a kiss upon her shoulder,” he sang in “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over.”)When he tragically passed away in 1997 at only 30 years of age in an accidental drowning, Buckley became a cult hero.

But to those who knew him best, Buckley existed as more than a myth or a legend; he was a son, lover, and friend. Berg, in her decade-plus long pursuit to tell his story, wanted to expand upon the narrative the singer left behind, both as an individual and a musician.

“I felt the pains of a man who was so talented and had a father [singer-songwriter Tim Buckley] he met one time that he was compared to over and over again throughout his career. I just could not imagine how difficult that must have been for him,” Berg tells POV over Zoom ahead of the film’s North American theatrical release.

She continues, “Also, I am a single mom, and I understood that there was a complicated relationship with his mother. I really wanted to tell an intimate family story.”

In order to portray Buckley holistically and personally, Berg first sought out Mary Guibert, Buckley’s mother, in 2007. While Berg’s initial efforts proved unsuccessful, Guibert gave her reason to keep trying: “It wasn’t like, ‘Go away, never call me again.’ It was more like, ‘I’m not ready.’ So I was able to sustain a little bit of hope.”

Prior to Berg’s documentary, several attempts had been made to create a dramatized biopic of the singer’s short life, including one led by Brad Pitt (who serves as executive producer of It’s Never Over) and one as recently as 2021, which attached Reeve Carney as Buckley. Guibert has seemingly been involved in every start and re-start along the way, as productions have fallen through over the years. (During the past decade, Berg’s directed docs on notable figures including Janis Joplin and Evan Rachel Wood.)

Berg posits that Guibert wants “to see her son’s legacy brought to life while she [is] still vibrant and alive, [and] to be a part of making sure the story was told the way it should be told.”

However, Berg assures audiences that Guibert’s involvement didn’t impede in the telling of Buckley’s story in an authentic way, describing it as “a perfect situation.” Berg says that after Guibert gave permission for the film to be made, she simply offered her the keys to the storage container filled with Buckley’s items and let the filmmaker roll.

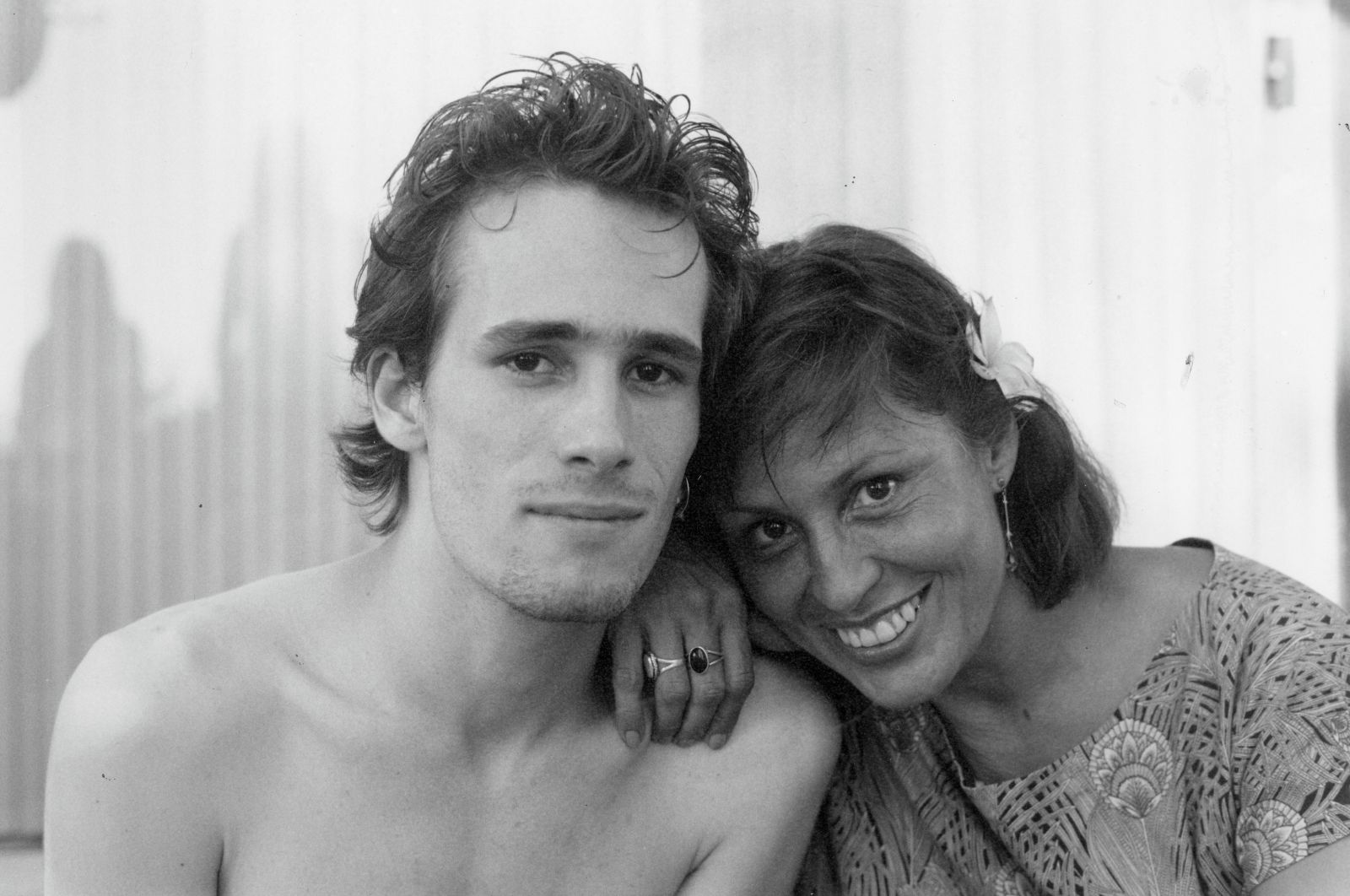

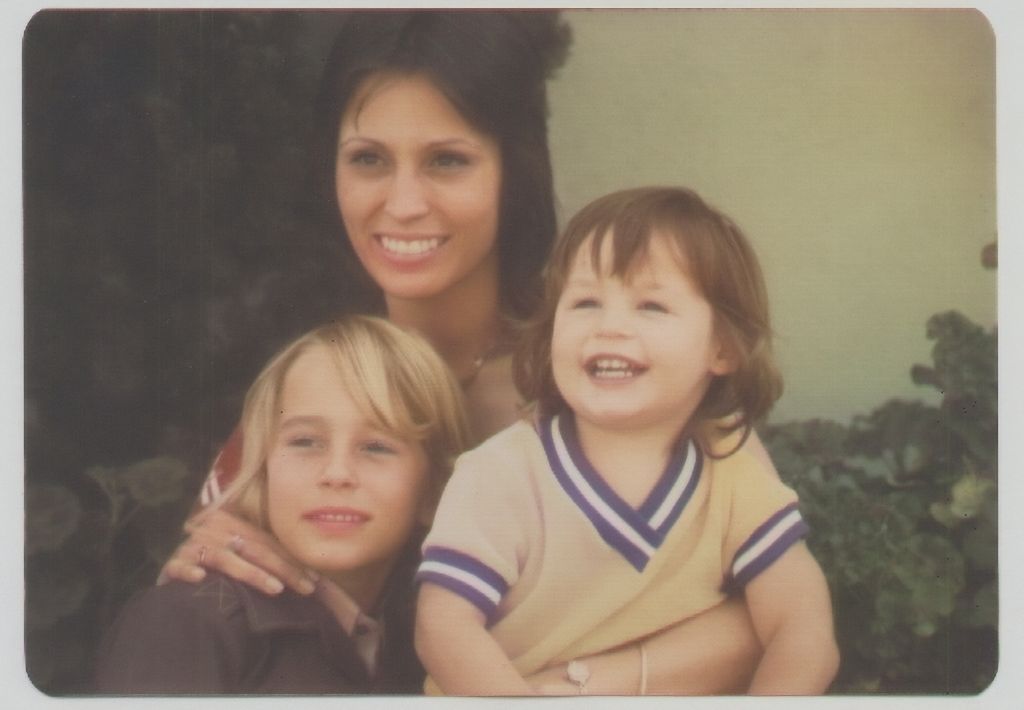

While Guibert kept her distance behind the camera, her presence looms large in front. Guibert was only 18 years old when she became pregnant with Buckley, creating a different mother-son relationship than most.

Berg notes, “They kind of raised each other, but she was his mother, and he knew how hard she had to struggle to be able to do her job as his mother.”

Using voicemail messages that Guibert saved, Berg demonstrates their dynamic. In one, Buckley dresses Guibert down for publicly (and aggressively) addressing tabloid fodder concerning the singer, telling her to, effectively, grow up. But in his final message left to Guibert, the sheer love and adoration he had for his mother is clear.

Berg describes listening to Buckley’s messages, saying she could “feel his passion and emotion,” with the final message in particular bringing her to tears many times. This is the part of Buckley that Berg has been keen to show in her film. The side of Buckley that enabled him to communicate such profoundly personal thoughts, whether in a voicemail to his mother or through songs for fans.

“I really saw him as a feminist, because of how he was able to sing and how he was able to articulate himself in his songs and speak on such a deep level,” says Berg. “It didn’t feel ‘masculine’ to me at all compared to so much of the music of that time.”

Musician Rebecca Moore dated Buckley prior to the release of Grace and is widely considered his muse for many of the album’s songs. Berg beautifully expresses their relationship as Moore being the girl whom Buckley “dreamed of as a young man in his journals.” Moore appears in the film, recounting their time together in the years prior to Buckley’s success, while Joan Wasser (known professionally as Joan as Police Woman), his partner at the time of his death, gives insight into the singer’s life following Grace’s release.

“Rebecca [was] his first love. It was pure, but clearly he didn’t feel ready enough, and there was a lot going on at that time,” Berg shares. “Joan understood his world a little bit more, because she was travelling in the same way that he was. They were more of a partnership, I think.”

Both Moore and Wasser shared Guibert’s reluctance to participate in the film, an apprehension Berg understands. “They didn’t have this desire to share the story with the world. They have their own Jeff Buckley box in their hearts that they wanted to hold on to.”

By bookending It’s Never Over with Guibert, Moore, and Wasser, Berg positions the film as a personal and intimate tale through the words of, arguably, the three most significant women in Buckley’s life, each sharing a version of the person only they knew.

While Berg’s film, of course, delves into his musicality and artistry, by centring the story around this trio, she creates a unique tribute to Buckley that echoes her own version of him: “He was genre defying,” she observes. “He was gender defying: He was this anomaly.”