“There’s a line in the movie where [Stephen] Malkmus says, ‘I’m inspired by things that sound like shit to me,’ and that was kind of the approach to it,” says Pavements director Alex Ross Perry (Her Smell, Queen of Earth). “I’m not inspired by these cliché biopics artistically. I’m inspired by them because of what they represent.”

Pavements blows music film cliché to smithereens. This exhilarating kaleidoscopic doc injects vitality into an oversaturated field. When nearly every musician, from veteran to ingénue, has a documentary, dramatic biopic, or both, celebrity bios face a dearth of originality these days. However, Pavements understands that rinse and repeat formulas are great for shampoos and for not bands.

This makes the doc’s portrait—or portraits—of the American indie band Pavement doubly refreshing. For audiences, including a viewer like myself, who might approach the film with minimal familiarity of the American indie band that had a measure of success in the 1990s and found new audiences in their 2010 and 2022 reunions, Perry’s hybrid film inspires a sense of discovery. Sure, one leaves the film wondering if Pavement is as real a band as Spinal Tap. But Pavements motivates a dive down the rabbit hole of pop culture arcana to put the pieces of the film together. It’s an invitation to explore the band’s offbeat lore and eclectic music.

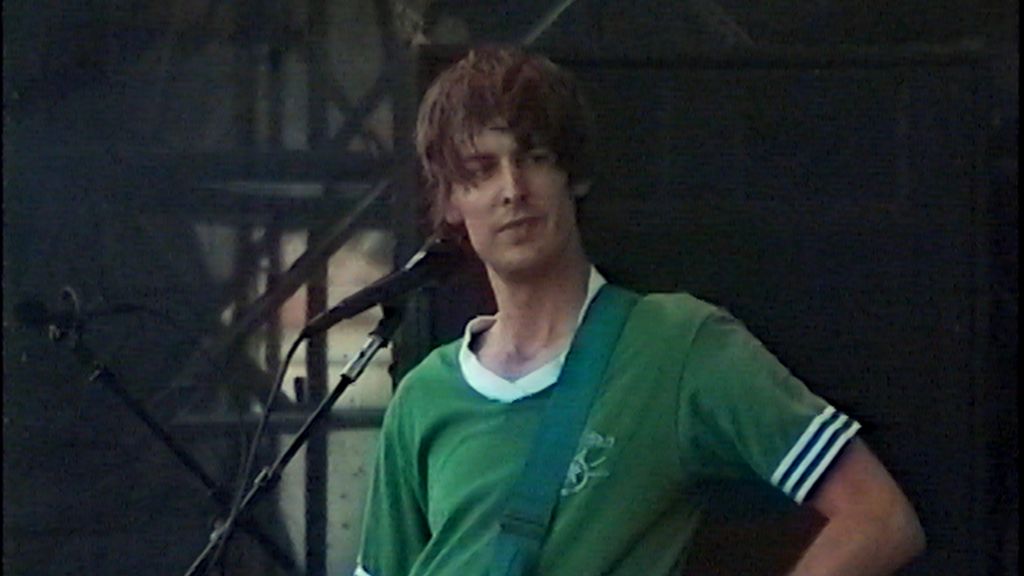

Pavements offers a shapeshifting take on the band to illustrate how a conventional snapshot doesn’t do them justice. The film includes four or five strands, depending upon how one evaluates it. There’s a conventional(ish) behind the scenes rockumentary thread that follows Pavement as they read for their 2022 reunion tour. Then there’s a semi-bogus Pavement museum—which actually did briefly open with a collection of memorabilia both authentic and invented. Then there’s a musical thread about Perry’s 2022 stage workshop Slanted! Enchanted! A Pavement Musical, a spin on jukebox musicals with actors like Zoe Lister-Jones bringing the songs of Pavement to life in offbeat, off-Broadway fashion.

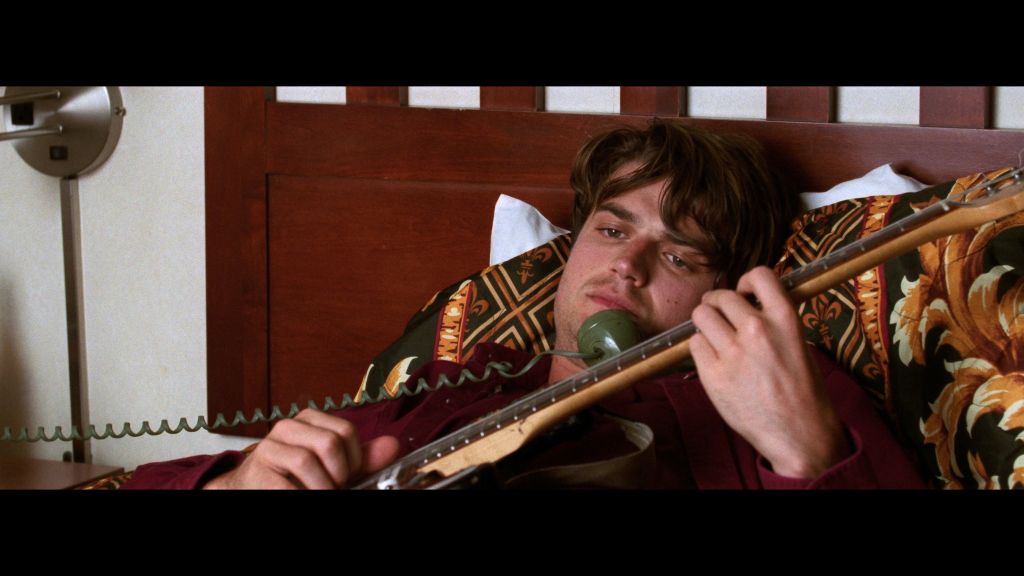

Then there are scenes from Range Life, a fake musical biopic of the clichéd Bohemian Rhapsody variety, featuring Joe Keery as Stephen Malkmus, Fred Hechinger at Bob Nastanovich, Nat Wolff as Scott Kannberg, Logan Miller as Mark Ibold, and Griffin Newman as Steve West to round out the band, with Jason Schwartzman as Matador Records’ Chris Lombardi and cameo appearances by the obligatory “For Your Consideration” watermarks that critics and voters see annually during award season. These threads come handsomely sandwiched between a wall-to-wall collage of archival material and concert footage. Pavements combines for an immersive and active experience that calls upon audiences to decode the band on their own.

Perry says that he crafted the different threads sequentially with the museum coming first, followed by the musical and few months later. “Then we shot the biopic in secret, unlike the other two things, the following spring, so six months later,” he notes. Perry says it was enlightening to see how facets of the projects played off one another in cultural commentary and fandom, particularly the musical. “It was just announced as a workshop performance: Two days, get a ticket. No one knew this was part of a broad experimental Pavement mosaic film,” says Perry.

Reviews of the musical prove especially fascinating in this context, as well as within the cultural conversation about fandom, celebrity, and biography. For example, Spin’s Tatiana Tenroyo references the strange experience of seeing a poster for the musical at the Pavement “museum” and assuming it to be fake, only to be surprised weeks later to learn that the musical actually existed.

Tenroyo says the musical “fails spectacularly” and notes an observation that, while harsh, perfectly reflects the musical thread’s role within Pavements: “[W]e get this absolutely bewildering spectacle that nobody should have been forced to pay for, with corny group dance numbers that don’t fit the tone of the original Pavement material at all, shaky performances, and an unimaginative set…Perhaps the only way to enjoy Slanted! Enchanted! is as the punchline of a joke nobody needed to tell, involving some of the most original indie rock music of the past 30 years painfully recast as effervescent, choreographed dance numbers you’d see in a production like American Idiot.” The latter ironically references the kind of derivative musical that Pavements pushes against. And one that Perry actually references as research during our conversation.

Alternatively, Perry notes that some reactions to the musical illuminated the interplay between the film’s threads. “Rob Sheffield from Rolling Stone online, who’s a huge fan of the band and a very relevant critic commentator of this era, saw the musical and loved it for what it was. Loved it for what it said about the band, what it said about legacy and nostalgia and all the rest,” observes Perry. Sheffield’s review calls Slanted! Enchanted! “utterly bonkers,” the “ultimate absurdist theater experience,” and “a bold new breakthrough for the indie-rock musical, an idea whose time has finally come.”

Perry says it was enlightening to read that review while Pavements was still a work in progress. “He wrote this really great piece about [the musical] that was gas in the tank, because we just said, ‘He doesn’t know this is for the movie. The movie doesn’t exist yet. He hasn’t seen the movie,’” says Perry. “Everything he says here is what we are going for in a movie that doesn’t exist yet. If this guy is our target audience—a smart intellectual critic who is an authority on nineties’ music and culture—and we take what he saw and bottle it, then that’s what we’re aiming for. It was exciting to use these pieces and the museum as little canaries in a coal mine to stress test the broader conceit of the movie.”

The different threads of Pavements jam together in a unique experience with enough of a linear narrative to chart the band’s trajectory while illuminating the substance of their music in less straightforward fashion. Working again with his regular film editor Robert Greene, himself a noted documentary filmmaker whose works including Kate Plays Christine and Bisbee ’17 have integrated elements of non-fiction filmmaking and performance, Perry says Pavements really came together in the edit through someone who understood the collision between form and subject.

“We’re playing in his sandbox with this movie and we’re doing it with his all-time favorite band,” says Perry, noting that it’s his fifth time working with Greene. “Not a single other person on earth who could have edited this movie at all, much less the way he did it. What he pulled off here is Herculean in an unfathomable degree, and he did that with the passion that only this band’s number one fan could have harnessed.”

Perry, whose previous works have all been dramas, but by no means conventional ones, adds that elements of Pavements’ approach echo Greene’s fusion of documentary fiction and performance. (Perry’s second documentary Videoheaven, about the role of video stores in film culture, is out in theatres now.) Pavements uses the musical and fake biopic to explore the fissures within rote artistic portraits of iconoclastic subjects in ways that a film like Bisbee ’17 using performance to excavate gaps of recorded history.

“I was making a film in some ways similar to the work he does, exploring some themes of performance and processing the past through documentary cinema, meta-fiction, but doing it with the subject that’s so close to him,” notes Perry. “For him to be directing might have skewed the temperament a little close to hagiography because he loves the band more than anybody. But I didn’t shoot it that way, and I didn’t conceive of it that way. But then he edited that way. That trade-off, I think, became the central tension that makes the movie better than the sum of its parts, in my opinion.”

Pavements plays with levels of fandom from the outset. For example, an early title card introduces the “important and influential band that has ever existed.” The line appears several times throughout the film—perhaps more frequently than do tangible references to the band’s impact or hits. One doesn’t necessarily leave Pavements remembering any songs, although “No More Absolutes” and “Here” make great impressions in the musical thread.

Perry admits that the title card serves as a red herring and a guide to the cinematic malarkey. “It appears, like, a minute into the movie and is a lie. It’s not an accurate statement by any measure of fact, other than that this is a highly beloved and acclaimed band for, I don’t know, a hundred thousand people. That is a fact,” says Perry. “We say that at the beginning of the movie as a way hopefully of letting people know, ‘Don’t trust anything you see in this movie.’ They are not the world’s most important/influential band. Clearly this movie is taking place in a world where that is true instead of a world where that is subjective. Therefore, this movie must live outside of reality.”

With Pavements working several gears to convey the band’s story, the film inevitably plays differently depending upon the level of knowledge one brings to it. Perry says he ultimately didn’t worry too much about catering newbies or hardcore fans. He says that the film’s shape gives anyone a way into the Pavement experience. “If the movie is good, I enjoy a documentary film about a subject I know nothing about,” says Perry when it comes to approaching music docs.

“Nobody involved here is that much of a novice, and obviously throughout the process, you’re showing the movie to people who are who are not a fan. They don’t know the band at all, and those reactions are quite important because they help keep you honest. They’re more important than the reaction from a diehard fan who says, ‘I know the band better than you ever will, and here’s what this movie doesn’t do. Here’s what you got wrong.’ That reaction is worthless. It’s worse than trash, it’s just not even worth hearing.”

Perry acknowledges that Pavements has to hit some key beats in telling the band’s story, so it isn’t totally immune to the rigours of biopic filmmaking. “We don’t invent things because we wanted to use archival to illuminate the contradictions between what happened and the way that cliché films would maybe embellish or invent their version of what happened,” Perry explains. “But much like all cliché music films, we’re able to unite our dramatic climax around something that happens ignominiously on stage at a concert, which for us is our mud flinging.”

The film culminates with a scene from Range Life that dramatizes the infamous concert at Lollapalooza 1995 when the band was credited for ruining the music festival. The concert sees Pavement going out in a barrage of mud and Kannberg mooning the crowd in response. It’s a wildly cinematic shitstorm—the kind of thing one would hardly believe in a movie—that encapsulates the collision between an iconoclastic band and an unruly mainstream audience with basic taste.

“In other movies, that scene might be the Live Aid [in Bohemian Rhapsody] or Elton John at Dodger Stadium [in Rocketman] or there was a big one of these at the end of the Bob Marley movie [One Love] that took place in Trench Town, Jamaica,” says Perry. “It was, like, you name it. So we’ve got ours. It’s just the mud scene. But that’s just to show you can’t get away from these beats even when you’re doing them in quotation marks.”

Pavements defies fervent nitpicking by design, in some ways revolting against the ways in which, say, Bob Dylan fans might complain about a fan calling the singer “Judas” at Newport instead of Manchester in last year’s biopic A Complete Unknown. “You’ll never please those people,” Perry continues, suggesting there’s more hope in interested cinephiles open to new approaches or subjects.

The director likens the engagement with fans versus casual moviegoers to his own willingness to watch anything if the mood’s right. “I was as surprised as anybody that last year’s Céline Dion documentary was a totally incredible and shockingly raw piece of nonfiction portraiture,” says Perry. “I thought it would just be a puff piece with great archival, and that’s what I wanted. It turned out it was a harrowing depiction of illness and grief, and it was a great film because of that. I didn’t know that when I went to watch it.”

Perry agrees that the Dion doc stands as an anomaly in a crowded field, but admits that everything has become “completely basic and cookie cutter” in culture and that it’s hit a point of no return. “The biggest problem would be that no band wants to take a risk. It’s a miracle that I found one here: they found me and that my ideas were risky and that they were all in,” notes Perry.

The director adds that risky projects seem like a thing from a bygone era, something that today’s nostalgia culture ironically forgets, but Pavements remembers. “But nowadays, everyone just wants to play it safe. Taking the audience out of the equation,” he notes.

“The worst thing that could happen is that bands that could take a risk because they have the legacy or it’s in the nature of who they are to be risky, don’t want to take a risk. That’s the problem that hopefully doesn’t get any worse, but I’m sure it will,” says Perry.

“The admirable goal should be and must be a bespoke film about our chosen subject that could only exist for them. You could make this exact movie about any band. You could take any band and make a movie that has put their songs in a musical, cast actors to play them, smash it all together in the edit. For most bands, you’d look at it and go, ‘Why the hell was this the approach for this movie? What does this have to do with this band?’ Whereas for us, what we were hoping for was people going, ‘Wow, this is the most perfect approach for this band. They really found that.’”