Aanikoobijigan [ancestor/great-grandparent/great-grandchild]

(USA/Denmark, 80 min.)

Dir. Adam Khalil, Zach Khalil

Prod. Steve Holmgren, Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil, Grace Remington, Jacque Clark, Franny Alfano

Programme: NEXT (World premiere)

“What’s the difference between an archaeologist and a grave robber?” an elder asks in Aanikoobijigan. “A degree,” he laughs.

While the elder refers to the fancy piece of paper that champions the archaeologist’s credentials, this innovative documentary suggests that the distinction between an archaeologist and grave robber is a fine one. Aanikoobijigan tackles a history of colonial violence that finds victims in the past, present, and future. It excavates the complicated legacy of museums and archives that house the remains of Indigenous people in America. In 2026, the conversation about who has the right to human remains endures as a surprisingly relevant one. Simply put, many institutions that give rise to the liberal arts philosophies that champion decolonization don’t want to do the work it entails.

Brothers Adam Khalil and Zach Khalil speak with elders across numerous tribes as they seek to repatriate their ancestors’ remains. Even after legislation passed in 1990 to return the bodies and bones of Indigenous people to the Nations that claimed them, the fight between human decency and matters of perceived scientific importance wages on.

Aanikoobijigan testifies to the necessity of laying these bones to rest. An interviewee explains the Indigenous perspective of returning the body to the earth to continue the cycle of life. As an elder’s body decomposes, his or her memories nourish the trees and other plants. A proper burial therefore keeps knowledge alive. To keep bones in campus storage simply holds hostage a history of stories and traditions.

The Khalils evoke this cyclical nature with a pop-art style that imbues vérité footage with a full spectrum of colour. The film follows the idea of return as members of the Michigan Anishinaabek Cultural Preservation and Repatriation Alliance (MACRA) present a united front to this form of academic racism. The fickle nature of the laws, moreover, puts the burden of proof on the Nations to clearly identify and claim any remains. That point becomes especially difficult when regions like Michigan are home to so many tribes that can’t one can’t easily distinguish with a simple DNA test. The tribes therefore seek a common goal: no community will be at peace until all the souls of the ancestors are free.

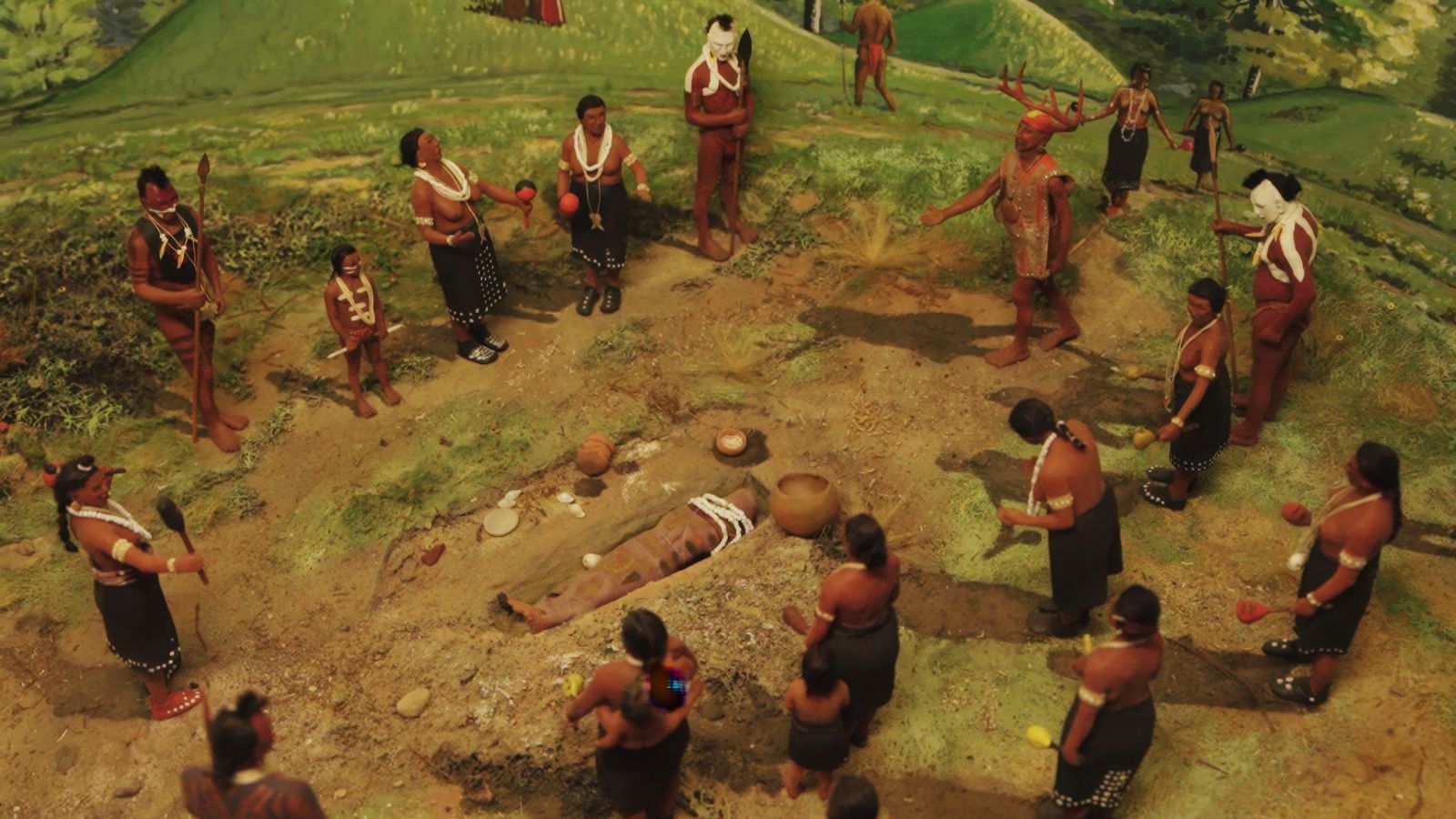

Aanikoobijigan situates this confrontation within a larger history of racism. The brothers introduce Hollywood movies that play with the trope of the Indian burial ground—Poltergeist, Pet Sematary—and present the argument that treating sacred burial sites as a novelty reflects settlers’ unease with America’s colonial past. To cede ownership of Indigenous remains is therefore to admit complicity in the violence that wiped millions of people from the Earth.

Likewise, a trip through the archives reveals the blatant racism of the institutions’ argument in favour of keeping the remains. The sense of ownership over Indigenous bodies simply gives colonial violence a new form. The archaeologists go on the defensive and suggest that the very idea of repatriation puts their field at risk. But the Indigenous interviewees make a clear point: returning ancestral bones honours the very history these academics study. A bone is more than a tool for learning.

The doc features a mix of striking visuals, from experimental vignettes that present images of cremation and return to the pixelation of bones and remains. There’s a refreshing refusal to perpetuate the violence of putting ancestors’ bodies on display.

But the most compelling pieces of evidence are the vérité scenes of elders lining up to claim boxes of their ancestors’ remains. As employees remove tag after tag from the boxes and fastidiously document the return of the remains, checking off items in an extensively catalogued list and leaving rows of empty shelves now that the bones have gone home to rest, Aanikoobijigan hauntingly evokes the sheer scale of this violence. It’s not an easy sight, but hopefully one that provides a degree of closure.