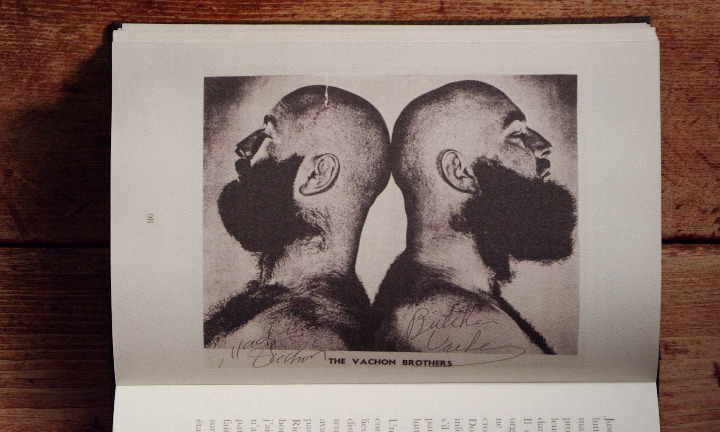

Paul Vachon is the surviving member of a Canadian dynasty. He’s the reigning king of the ring. The octogenarian recalls his family history in The Last Villains. The story mostly centres on the fame that Vachon enjoyed with his brother, Maurice, who went by the moniker Mad Dog while Paul cut up the crowd as The Butcher. Directed by Thomas Rinfret, The Last Villains is an engaging character study that should appeal beyond die-hard wrestling fans. Vachon is a good storyteller and retains the showmanship of his wrestling years. He captivates a viewer while telling a story complete with twists and tragedies.

The Last Villains is the story of Vachon’s journey from world famous wrestle to shopping mall Santa Claus. One wishes that the doc explored the challenges of the subject’s post-wrestling career more willingly—great nuggets of faded celebrity appear fleetingly—but as a svelte celebration, it’s nevertheless appealing. The doc runs with a theme of Vachon’s work, which also happens to be the title of his memoir, When Wrestling Was Real. The film is a look back at his family’s legacy as well as the heyday of a sport before it became a bastardized gong show. The Butcher emphasizes his broken and battered body as evidence that wrestling is real. He hobbles around well enough in a walker, but the evidence of hard hits is clear. He could take a body slam just as well as he could deliver one, and he doesn’t have any regrets about the prices his paid.

Rinfret frames The Last Villains in the form of a fable as pages of a storybook turn with the passage of time. Some chapters bring out the greatest hits, like pleasing fans at conventions, or enjoying such iconic status in Canada’s cultural ethos that then-Prime Minister Brian Mulroney even wished Maurice well when he lost his leg following an accident. The doc understands that the Mad Dog and the Butcher became Canadian icons at a time when few Canucks could attain a wide reach on television. Understanding the power of the medium, the brothers gave audiences wrestlers they could root for as a form of national pride.

The harder moments in Vachon’s story, however, give the films its power. For example, one segment features Vachon’s protégé Luna, who energized audiences with her semi-shaved head and raucous attitude until she died at a young age of 48. Vachon describes her death as a face-plant into a pizza, delivering the memory with appropriately unsentimental frankness. The costs to family echo throughout the doc as the Butcher recalls the time he can’t reclaim with his kids. A trip to the family reunion in Alberta conveys the distance between the Butcher and his now-adult children. They don’t begrudge their father his success, but Rinfret observes the inevitable toll to one’s personal relationships that arises when professional success comes at the expense of family.

The Butcher offers few regrets in The Last Villains and this character is less a eulogy and more an extension of Vachon’s memoir. The film shares the family’s story in the same cadence of unsentimental frankness with which Vachon tells the tale. This is an old-stock doc portrait that doesn’t pull any punches.

The Last Villains: Mad Dog and the Butcher screens at the Canadian Film Festival via Super Channel on April 10.