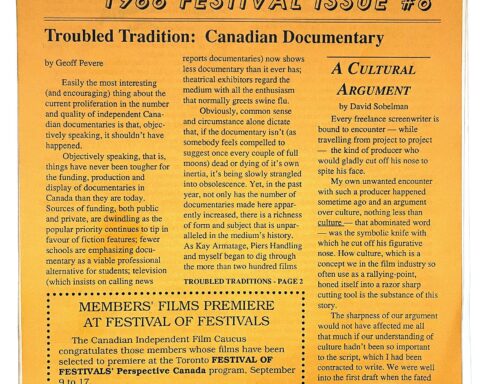

Film histories are highly selective and reflect the biases, tastes and viewing experiences of those who write them. I hope that my following sampling of inward-looking political and activist docs may help readers discern a cursory chronicle of doc dissent in a Canadian context. Speaking of Cancon, one of Canadian cinema’s enduring features describes a dearth of exhibition opportunity, a condition pronounced as a cinema of absence. Northrop Frye’s ‘garrison mentality’ may have once described Canadian art and literature, but the collective inertia with regards to creating viable visibility for our cinema might be described as a case of cultural self-neglect. Perhaps it’s time to shift energies from the effort to make documentary the national art to addressing the problem of access. Bruce Elder once postulated on “the cinema we need” in this country; I propose a reboot: “the cinema we need to see.” With that in mind, the films mentioned below are more readily accessible than legions of other rabble-rousing fare left on this article’s editing room floor.

Rooted in Realism, Sort Of: The 1940s to the 1970s

Canadian cinema is rooted in realism and its attendant creative manipulation, beginning with the 1939 founding of the institution responsible for interpreting Canada to itself and the world, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). While the NFB has been a beehive of political filmmaking since its inception, its early output tended toward WWII propaganda and nation-building. One of the NFB’s post-war political shorts, Norman McLaren’s 1952 animated anti-war film Neighbours, may not seem to be a true documentary, were it not for the fact that it won an Oscar for best documentary short. This genre-bending quality points to another distinguishing characteristic of Canadian cinema, that of transgression. Six years later, Michel Brault and Gilles Groulx would put cinéma direct, or Direct Cinema, on the global stage with a deceivingly simple film that retains its political acumen for not only celebrating the life of rural Quebecois (a people too often figured as the negatively-charged inverse to Canadian nationalism), but for defying the board in the first place by making Les raquetteurs. Brault would go on to direct one of the most important political films in Canadian history, the Brechtian docudrama Les Ordres (1974), which compellingly dramatizes the injustices of the Canadian federal government’s enacting of the War Measures Act during the 1970 October Crisis in Quebec. For his part, Groulx would direct a seminal film that helped position both Quebec and the NFB at the vanguard of 1960s political cinema: Le chat dans le sac (1964) is another transgressive work that uses the coming-of-age of a twenty-something Quebecois man as a metaphor for the political coming-of-age of the province as a whole.

Pioneering in its own right, and exemplary of the importance of public broadcasting as a platform for progressive discourse, is the NFB-produced, CBC-commissioned docudrama Crossroads by Don Haldane, an innovative and bold film for 1957, where socio-political issues around an interracial marriage are sensitively probed. In recent years, CBC television may have become a repository for cringe-inducing comedy, franchise drama and unReality TV, but there was a time when it produced landmark docs like Beryl Fox’s The Mills of the Gods: Viet Nam (1965), a powerful exposé of American abuses in the Vietnam War. Just two years later another CBC-commissioned doc would garner critical acclaim, albeit not on television. Allan King’s Warrendale (1967) stunned audiences with its observational look inside a controversial Ontario mental health institution and its troubled young patients. King refused to comply with the CBC’s insistence on a profanity-free cut, so Warrendale — heralded as a “masterwork” of Canadian cinema — never aired on TV. Pair this canonical doc with the more recent and independent The Inmates are Running the Asylum: Stories from MPA by Megan Davies (2013), about the radical mental health group MPA in Vancouver, and discover fascinating alternative histories to dominant approaches to mental health in Canada.

While divine retribution has never yet been forthcoming for American imperialism, another CBC doc, made some thirty years after The Mills of the Gods, is still pertinent as the US enters the Trumpocene and on the heels of the violent articulation of hatred carried out in a Quebec City Mosque on January 29, 2017. Peter Raymont’s Hearts of Hate: The Battle for Young Minds (1995) shocked unknowing Canadians by confronting a smug nationalism that consistently denies the existence of “American-style” racism and white supremacy in Canada. Hearts of Hate reveals a disturbing dark side to Canada’s officiated Multiculturalism, showing members of racist organizations The Heritage Front and the KKK espouse their hate-filled views inside friendly Canada. Couple this myth-shattering film with Amy Miller’s equally upending Myths for Profit: Canada’s Role in Industries of War and Peace (2009) and watch the dominant narratives recoil to the mainstream corners from whence they came.

Speaking of dominant narratives, Tanya Ballantyne Tree’s extraordinarily candid short on adolescent sexuality The Merry-Go-Round (1966) challenged conservative approaches to sex education while also providing, according to Thomas Waugh, a “demolition of the NFB voice-of-God expert voice-over—at long last,” thus signalling “a new sexual morality but also a shift in documentary modes.” In fact, the NFB’s progressive approach to morally charged topics has been scandalizing conservatives for decades. Robert Anderson’s BAFTA-nominated Drug Addict (1948) was banned by the US government for its sympathetic portrayal of addiction and arguing that drug addicts should be treated as patients, not criminals. It’s a political gem that, along with the NFB’s Monkey On the Back (Julian Biggs, 1956), Nettie Wild’s socially intersectional and personally intimate Fix: Story of An Addicted City (2002) and Antoine Burges’s inimitable and disorienting East Hastings Pharmacy (2012), provides an unconventional introduction to the health, social, political and cultural contexts of drug addiction in Canada.

Fix: The Story of_An_Addicted_City from Canada Wild Productions on Vimeo.

Challenge for Change

John Grierson, founder of the NFB, charged that film should be a tool for social change. Challenge for Change and its French-language counterpart, Société nouvelle (CFC/Sn), the NFB’s internationally scrutinized experiment that answered that call, ran from the late 1960s until the early 1980s, eventually producing over 200 documentaries and even a revolutionary journal called Access. CFC/Sn was an audio-visual oddity that conveys another Canadian cinema quality: earnestness. CFC/Sn combined several government agencies’ concerns into one programme, resulting in films mandated to tackle social issues of every manner—from urbanization to alienation to workplace safety to poverty—by way of alternative media’s triumvirate of principles: participation, access and civic engagement. In principle, videographers (using new Sony Portapak technology) would make films with “citizens” rather than merely about them. The dualism of process cinema vs. product cinema is but one notional extension of CFC/Sn’s many community video projects, the latter exemplified by the famous “Fogo Process,” which refers to Colin Low’s video work with members of Newfoundland’s Fogo Island. Low worked with community members who participated both as filmed subjects and co-creators in the composition of the short films made for the series. Other CFC/Sn films like the two-part Encounter with Saul Alinsky (1967), featuring the famous American community organizer and writer in dialogue with Canadian groups, and Encounter at Kwacha House – Halifax (1967, Rex Tasker), a historically vital account of Black Haligonians discussing a boycott of racist businesses, focused on the transformative power of dialogic encounters.

The most important political documentary to emerge from the CFC/Sn programme is the provocatively titled You Are On Indian Land (1969) by Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell (Mohawk) and veteran NFBer Mort Ransen, released just nine years after Indigenous people in Canada became ‘Canadian citizens.’ The film focuses on the blockade of a bridge on the St. Regis reservation that spans Canada and the US. In a defiant act of both recognition (of Indigenous land rights) and refusal (to accept colonial borders), the Mohawk activists claimed right of passage between the two countries, citing the 1794 Jay Treaty. The familiar colonial scene of Indigenous blockaders resisting police unfolds in this commanding film, which is an important dissenting doc for three distinct reasons: it represented Indigenous people as active protagonists on camera; it centred Indigenous voices articulating Indigenous history, knowledge and experience (and thus can be considered a decolonizing text); and it ushered in Indigenous participation in the filmmaking process.

You Are on Indian Land, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Canada’s cinema, as Michael Dorland has slyly noted, is “close to the State/s,” and as such, there are political pros and cons to consider in its proximal relationship with the Canadian government and with the US—contiguities brought to light in Mitchell’s film. On the critical side, the NFB doesn’t accurately reflect Canada’s diverse demographics in its upper-level decision-making ranks. On the plus side, the board has been home to some of Canada’s most important Aboriginal filmmakers. Among the earliest Indigenous works is the arresting proto-music video that conveys the historical plight of Indigenous peoples in North America, The Ballad of Crowfoot (1968) by Willie Dunn (Mi’kmaq). Dunn worked with Martin Defalco four years later to direct the historical corrective on the 300th anniversary of the Hudson Bay Company, The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1972). And while the NFB’s Indian Film Unit, comprised of Dunn, Noel Starblanket and other Indigenous artists/activists, short-lived, an outsider would emerge to ensure Indigenous cinema’s place into the future.

Pluralism and Contention: The 1980s to the New Millennium

Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki) was initially hired at the NFB in 1967 to consult on film projects about Indigenous people. But after answering one producer’s question about appropriate depiction of Aboriginal subjects with “Let our people speak,” Obomsawin would take charge of the representational reins herself. Starting in 1971 with Christmas at Moose Factory, Obomsawin has created an astounding filmography (fifty titles and counting) mostly focused on the lived experiences of Indigenous people in Canada from coast to coast to coast. Among her most politically impactful works are Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986), about the wreckage exacted on Indigenous children in foster care and which helped change policy in Alberta; No Address (1988) about homelessness in Montreal; Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) a film about the 1990 Oka crisis that, arguably more than any other contemporary Canadian documentary, shifted public debate and political discourse in a more progressive direction; Incident at Restigouche (1984) where Obomsawin responds to Quebec’s Minister of Fisheries as he waxes Christian ontology: “You’re not going to tell me the apple story, are you?”; and, more recently, The People of the Kattawapiskak River (2012) where we see toxic colonial architecture continue its legacy in a Northern Indigenous community wrestling with poverty and suicide (issues still inexorably linked to much of settler Canada’s excess and unawareness).

Compelling documentaries continued to speak truth to power in the 1980s. Notables include Terre Nash’s Oscar-winning anti-war short If You Love this Planet (1982), a rousing NFB film that, with Trump’s current nuclear arms race provocations, is more relevant than ever, and which prefigured the public-talk-as-film sub-genre popularized decades later in the Al Gore eco-feature An Inconvenient Truth (2006). That year also saw the NFB release a controversial take on a contentious subject: Bonnie Sherr Klein’s Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography polarized audiences with its perceived anti-pornography stance, while contributing to the “feminist sex wars” that would ultimately shift second-wave feminism into third gear. For a fierce rejoinder, pair Klein’s treatise with Bad Girl (Marielle Nitoslawska, 2001), an audacious feminist intervention exploring the sex industry, and ready the debate cue cards. To connect this program to an earlier equally bodacious work from the nineties, add Maya Gallus’s Erotica: A Journey into Female Sexuality (1997) to the women-and-sex viewing queue. Two years after Nash’s and Klein’s celebrated works were released, and as the country braced for a Conservative Prime Minister who would strike an anti-labour free trade deal with the US, Janis Cole and Holly Dale’s Hookers on Davie (1984) shook up the sex debate once more. This remarkable doc peered past reactionary headlines into the world of sex work in Vancouver with a compassionate perspective that shirked judgement in favour of humanism by crafting a visual proximal empathy between vulnerable communities and documentary audiences.

As the free trade era of Mulroney saw corporations reap benefits, a handful of political docs centred the issues of labour and poverty across the country. Among them, Sturla Gunnarsson and Robert Collison’s Final Offer (1985) took on an enormous responsibility when the filmmakers were given the equally immense privilege of documenting the machinations of contract negotiations between United Auto Workers and General Motors. The unstoppable Magnus Isacsson would deliver his own expositions on collective labour with Union Trouble (1991) and Maxime, McDuff and McDo (2002), about an attempt to unionize McDonald’s. Isacsson would also delve into the issue of poverty with the tenderly intense The Choir Boys (1999), a doc that echoes the vivacious documentary-musical from nine years earlier by Tahani Rached, Au Chic Resto Pop. Refusing familiar victim tropes, Rached stages brilliant musical numbers with the community that gathers around Montreal’s Chic Resto Pop, a restaurant with a social justice mandate.

Hands of History, Loretta Todd, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Back on the topic of women and work is the divinely defiant Who’s Counting? Marilyn Waring on Sex, Lies and Global Economics (Terre Nash, 1995), a film whose synopsis is in the title. Pivoting every so slightly one year earlier and toward women and art, Loretta Todd’s (Métis, Cree) Hands of History (1994) is an NFB doc that corrects the lacuna of representations of female Indigenous artists working in Canada, who in the film assert, “Canada is a picture that hasn’t emerged yet” and, “Our art has been defined by outsiders: the artefacts are there, but not our voice.”

On the art-related topic of queering landscapes, two stellar ’80s docs helped carve out a space in a decreasingly heteronormative country. Passiflora (Fernand Bélanger and Dagmar Teufel, 1985) may be one of the strangest postmodern films ever made in Canada, with its explorations of counter-culture, overculture and the hypocrisy of hierarchy memorably interpreted vis-à-vis the juxtaposition of the Pope’s and Michael Jackson’s visits to Montreal. Video artist and documentarian Richard Fung diversified the queerscape further with Orientations (1986), a doc about the under-represented lives of LGBTQ Asian-Canadians. Fung continued this story with a focus on queer Asian-Canadians living with HIV in Fighting Chance (1990) and the wonderfully reflexive Re:Orientations, which follows up with subjects from Orientations exactly thirty years later. All that said, no other documentary has so exquisitely queered form and content than Chelsea McMullan’s My Prairie Home (2013), a musical journey through Alberta and the prairies featuring gender non-conforming musician Rae Spoon and their unforgettably disarming moments of song, trauma, memory and grace. One year later Rémy Huberdeau’s Transgender Parents (2014) contributed to the topic of non-conforming gender roles and family with a mid-length documentary that not only challenges preconceived notions of trans parenting, but depicts family as a space of love, struggle and solidarity.

Two films marked 1992 with a boldness of vision, purpose and aesthetic strategy that may be at odds with Canadian cinema’s perceived understated nature (what I call humblecore). Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives by Lynne Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman has justifiably entered the queer classics pantheon. This NFB juggernaut blurs cinematic borders with its combination of documentary techniques and dramatized scenes of steamy sexuality. Transgressive for its genre border-crossing and depiction of lesbian love, this mistresspiece brashly features an older generation of women recalling forbidden loves of decades past. That same year, the NFB released the inventive Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media. Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s cinematic chef-d’oeuvre showed that documentary could be both politically engaging and wildly entertaining at the same time, while turning an entire generation on to a radical political thinker and activist.

The 1990s saw the Canadian government ratify NAFTA, shut down the cod fisheries, and send CF-18 fighter jets to the Persian Gulf. It was also a decade of continued unbridled resource extraction, from oil to timber, and rebel doc-makers responded in kind with passionate environmental films. Blockade (1993), directed by Nettie Wild, conveyed the struggle of the Gitskan and Wet’suwet’en to take control of the land (and protect the trees) in British Columbia. Only five years later, a landmark treaty was reached between the government and the Nisga’a First Nation in BC, where Indigenous self-determination became reality. Deforestation is linked to colonization in Bones of the Forest (Velcrow Ripper and Heather Frise, 1995), yet this lyrical doc also seeks to position loggers as part of the fallout from rapacious companies like MacMillan-Blodell. Back in Quebec, just one year after a referendum narrowly determined that province’s continued place in Canada, Magnus Isacsson’s Power: One River, Two Nations (1996) dug in deep to convey the complicated relationship between the Cree nation and dam-happy Hydro-Québec. That same year, the three-year-old Hot Docs film festival hosted an event called “Liberating the Real: Documentary’s ‘New Wave’?”: “An emerging strain of works rejects the traditional observational role of documentary to claim, instead, the perils and privileges of full authorship—as in fictional cinema.” It would seem that POV filmmaking had indeed arrived.

The New Millennium: A Pluralism of Perspectives

After the world recovered from the “perilous” Y2K crash on the eve of the new millennium, filmmakers dusted off their lenses and got back to the business of invalidating the veneer of trickle down economics. S.P.I.T.: Squeegee Punks in Traffic (2001) by Daniel Cross shifted the representational power on to the disenfranchised and heralded what would become a decades-long project by Montreal’s EyeSteelFilm to put visual culture tools and technology in the hands of those who were more often the subjects of others’ stories. These efforts would culminate in a unique online community project called Homeless Nation, signalling yet one more fracture in the one-nation myth of Canadian federalism. On the related topic of agency and structure Mark Achbar and co-director Jennifer Abbott broke doc box-office records with the provocative and unabashedly subjective The Corporation (2003), a film that follows the logic of the legal notion of corporate personhood to ask if the modern day corporation is a psychopath. That same year Min Sook Lee’s El Contrato offered more evidence to question the capitalist system by revealing the oppressive conditions under which migrant workers toil in Canada. Lee returned to this subject in 2016 with the disturbing Migrant Dreams, a film that confronts Canada’s draconian Temporary Foreign Worker Program. A year after Lee’s baring of agribusiness’s moral bankruptcy, Kevin W. Matthews would reveal the pyschopathy of corporate forest management in New Brunswick with Forbidden Forest (2004).

Films that offer systemic critiques from a progressive stance are what I have called “radical committed documentaries” (POV #92), and a few post-2000 efforts come to mind. Richard Brouillet’s 2008 essay on ideology, Encirclement: Neoliberalism Ensnares Democracy, tears into the tissues that barely hold together a functioning neoliberal and democratic society, while END:CIV–Resist or Die (Franklin Lopez, 2011) gives a platform to radical alternative views on society. Amy Miller’s The Carbon Rush (2012) convincingly proves that when capitalists design schemes for fixing the planet (in this case, climate change), only more devastation awaits. This point is echoed in Pink Ribbons, Inc. (Léa Pool, 2011), a doc that powerfully exposes the corporate appropriation of activism, in this case around breast cancer. Continuing along a registry of toxicity, Twyla Roscovich’s Salmon Confidential (2013) interrogates B.C.’s eco-destructive fish farms, which are destructively sustained through government and corporate collusion while Barri Cohen’s Toxic Trespass (2007) investigates the impact of myriad chemicals that we, and our children, come into contact with daily. Shoring up these titles is Sylvie Van Brabant’s solution-oriented eco-doc Earth Keepers (2009).

Since Canada’s current pipeline-positive government seems dead-set on keeping the country in the nearly extinct carbon economy, two docs that question the sanity of Alberta’s oil sands have a renewed urgency. H2Oil (Shannon Walsh, 2009) and Petropolis (Peter Mettler, 2009) are very different takes on this environmental calamity. Whereas Walsh deploys a more traditional approach to make her political argument, Mettler opts for an alternative aesthetic strategy, relying on eerie aerials and Werner Herzog-like voiceover. A year later Liz Marshall tackled the troubling issue of water privatisation and conservation in Water on the Table (2010), a passionate film that makes a good companion to another fervent filmic tract on the impact of ecological degradation, Chanda Chevannes’s Living Downstream (2010). The devastatingly intimate and moving Wiebo’s War by David York (2011) adds strange political and religious dimensions to ecology by focusing on an Evangelical Christian activist who pays the ultimate price for corporate malfeasance and government complicity.

Turning to another oppressive system, Indigenous filmmakers in the 2000s continued to probe the impact of colonisation on Aboriginal communities across the country. Métis filmmaker and academic Christine Walsh’s Finding Dawn (2007) put murdered and missing Indigenous women on the public radar, where beforehand there had been a damaging, complicit silence surrounding one of the most significant issues facing the country. Two Worlds Colliding (Tasha Hubbard (Nehiyaw/Nakawe/Métis), 2004) also shed light on a criminally under-represented story, that of the freezing deaths of Indigenous men given “midnight cruises” by police who left men like Darrell Night on the outskirts of Saskatoon in minus 20 degree temperatures. Inuit filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril explored the cultural impact of colonisation with her deeply personal 2011 doc Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos and recently stirred up the non-fiction film scene once again with her multiple award-winning crucial doc Angry Inuk (2016), which at long last represents seal hunting from an Inuit perspective. Non-Indigenous filmmakers can make for strong allies and accomplices in depicting Indigenous struggles for rights and equality, and the work of Martha Stiegman is exemplary in this tradition, including Honour Your Word (2013), an inspiring doc about Algonquin resistance and resilience in the face of provincial and federal governments set on breaking promises concerning Indigenous land.

On the topic of animals, two insubordinate docs agitated and activated in the 2000s. Maximum Tolerated Dose (Karol Orzechowski, 2012) and The Ghosts in Our Machine (Liz Marshall, 2013), both by Toronto filmmakers, take divergent aesthetic and discursive approaches to the topic of animal rights and abuse, the first with a poetic expression and the latter with emotionally stirring stories and indisputable research. Neither film preaches, and watched together, these two advocacy powerhouses might just shift a paradigm or two.

Dissenting docs frequently take on contemporary issues, but some peer into the past and consider history. Among those that disentangle political, cultural and social histories with an eye toward justice, four post-new millennial films demand (re)viewing. The Little Black Schoolhouse by Sylvia Hamilton (2007) explores the stories of survivors of Canada’s all-Black segregated schools, Fig Trees (John Greyson, 2009) is a creatively astounding documentary opera that looks at the AIDS activism of Torontonian Tim McCaskell and Zackie Achmat of Cape Town, and The Pass System (Alex Williams, 2015) examines Canada’s disturbing history of official racial segregation of Indigenous peoples, and Continuous Journey by Ali Kazimi (2004) dismantles the popular myth that Canada is a welcoming country to immigrants through the compelling use of rare archives to tell the tragic story of the Komagat Maru. These four essential-viewing films scrutinize the intersection of race, history and justice, and, together, insist we must never forget.

Fiercely independent documentary voices continue to take on unjust structures in the 2010s. You Don’t Like the Truth: 4 Days Inside Guantanamo (Patricio Henriquez and Luc Coté, 2011) is an effective force of advocacy for Omar Khadr’s release and repatriation, while The Secret Trial 5 (Amar Wala, 2014) is a deeply engaged film revealing the arcane and unjust treatment of five Canadian men suspected of terrorism. Dissenting docs often serve as platforms for under-represented radical voices, and two excellent examples of this invaluable aspect of political non-fiction can be found in Colonization Road (2016) by Indigenous filmmaker Michelle St. John (Wampanoag) and Status Quo: The Business of Feminism in Canada (Karen Cho, 2012). Both champion non-conforming voices that confront and undermine status quo attitudes toward Indigeneity and gender, respectively. Working in a similar register is a fabulous doc on a Canadian progressive art duo who employ a radical style of photography to document dissent: Portrait of Resistance: The Art and Activism of Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, (Roz Owen, 2011). Pair this last film with Magnus Isacsson’s Art In Action (2009), a doc following the radical art practices of the duo behind Montreal’s ATSA (in English, Socially Acceptable Acts of Terrorism) and discover a program about relationships, love, art, politics and commitment.

Future

Canada’s best political documentaries prick the inflated fantasies of nationalism, peer into the dark recesses of prejudice, chauvinism, imperialism, racism and colonisation, and create lasting fissures in the liberal façade of a friendly, functioning and fair democracy that has long defined this country. The films above intervene in the construction and continuation of dominant national narratives and mythologies while envisioning alternative worlds in which to live. And of course there are many missing (notably, many incredible shorts) that have struggled to be screened and seen.

On a last note, a new era of Indigenous cinema is upon us and it is these stories that are bringing and will bring new definition to this country. I look forward to the sense of place that Indigenous filmmakers like Amanda Strong, Michelle Latimer, Shane Belcourt, Roxann Whitebean, Lisa Jackson, Danis Goulet, Kelvin Redvers, Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, Kevin Papatie, Cherry Smiley (to unfairly single out a few names)—and other doc dissenters—will re-imagine and re-envision for all who call Canada home.

*For a much more thorough and rousing unsettling text see Indigenous activist, organizer and writer Arthur Manuel’s (Secwepemc) volume Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call (Between the Lines, 2015).