Is Raymond Depardon a photographer who is also a filmmaker, or vice versa? The question arises as one contemplates the truly prodigious 60-year output of this enigmatic visual artist, initially a photographer and reporter with French news agencies, but increasingly an independent filmmaker of some 50 documentaries and a handful of fiction films.

Depardon maintains he was a better reporter than photographer, and claims that film is his greater passion. Perhaps the question is academic because Depardon’s oeuvre is monumental on all counts. Just when it seems he has settled in for the long haul with film, he comes out with yet another major photographic project involving several years of monastic work, with accompanying exhibitions and publications. The disappointing reality is that the Frenchman’s work is little known or accessible in English Canada. Audiences in Quebec can look forward to his most recent film 12 jours, which premiered at Cannes this spring.

Raymond Depardon first appeared on my radar about 15 years ago when I viewed Profils paysans: l’approche, the remarkable first part of a trilogy about peasant life in France, which might be characterized as a montage of moving still lifes. Depardon is a pioneer of a new genre in documentary, a sort of tableau-vivant style characterized by wide, careful framing and extremely long takes in which characters speak to the camera in response to his infrequent questions, engage in conversation between themselves, and scrutinize the filmmaker in seeming wonder at what he is doing there. Action is minimal, but the faces, the language and the sets embody the ponderous peasant life of a rarely glimpsed France. These portraits of rural France and its denizens are magisterial, and hark back to Depardon’s own childhood on a working farm in Villefranche-sur-Saône, in the Beaujolais region of France.

The farm, still there but encroached upon by urban development, is where Depardon’s earliest photographs were taken, with a simple camera given as a present by his older brother. Rural life was not for him and in 1958, age 16, he hopped a scooter to Paris to apprentice with an independent journalist and photographer. Within a year, he was working as a freelance photo reporter for the Dalmas news agency, making a name for himself with paparazzi-type others. He sold them to Paris Match and with the revenue bought a second camera, a Rolleiflex, which he used for colour.

His first major assignment sent him to to the Sahara desert to follow a scientific expedition testing human ability to withstand extreme heat and thirst. The expedition ended in disaster as seven young servicemen disappeared on a hunting excursion. Only three were found alive and Depardon was there to capture the dramatic rescue. His remarkable photos were published in Paris Match and his career as a photojournalist was truly launched.

The Algerian war of independence was raging and Depardon was there to capture the ambient mood—street life, the pieds noirs, smiling French constables, fighters on both sides—a quotidian reality of normalcy belying that of imminent French defeat. It was there that Depardon’s identity as a documentarian was first revealed, and perhaps an inkling of his filmmaker self: he is both ethnologist and photographer; he sees history unfolding but focuses on its anonymous players.

Algeria proved foundational in other ways, marking the beginning of his love story with the desert where he returned again and again over the next 20 years—to Egypt, Chad, Mali, Algeria, Mauritania, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Niger. It is a relationship with Africa that has remained a lifelong passion.

By 1964, he had photographed conflicts in Algeria and Venezuela, the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, and been sent to Vietnam where he found himself in the heat of battle, trudging through rice paddies with South Vietnamese soldiers and their American military “advisors.” (He returned in 1972 to film the American retreat.)

Dalmas was a bold and innovative agency, a real scoop factory. Depardon’s editor gave him a 16mm camera and encouraged him to practice by shooting entire 10-minute reels without turning the camera off. He wandered Parisian streets and country fairs, getting his first experience with film, a dream he’d harboured since adolescence. These were the peak years of cinema direct and cinema verité. Rouch, Marker, Brault, Leacock and Pennebaker were active and though he admired their work and knew them all, he remained a loup solitaire, working at least half of his time as a photojournalist.

The history of France’s legendary news agencies is epic, and Depardon’s connection with them is a fascinating story. Having worked for Louis Dalmas for almost six years, in 1966 he and a shots of Brigitte Bardot and Marcello Mastroianni, among handful of reporter colleagues founded the Gamma agency, which would become its own legend. Its photographers and journalists covered local and world news through the late ’60s: May ’68, Israel and the Six-Day War, Vietnam, the American Civil Rights Movement, Chile. Photojournalists were credited for their images and it was a golden era for them. In 1968, Depardon and his close collaborator and celebrated news photographer Gilles Caron essentially broke the story of Biafra—the Nigerian Civil War, the bitter battles and the starvation that eventually caused millions of deaths.

Depardon refers to himself as a “savage” with a reclusive peasant soul, yet to all appearances he is fearlessly independent and driven, and has covered many epochal moments in recent history. He was there when the Berlin Wall came down, when the Americans pulled popularity in Chile, when Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, and during the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. He photographed sectarian wars in Northern Ireland, Chad, Lebanon, India and Pakistan and Afghanistan. He was at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. He photographed Nelson Mandela in the first days of his presidency, and Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher in Red Square, Moscow in 1961.

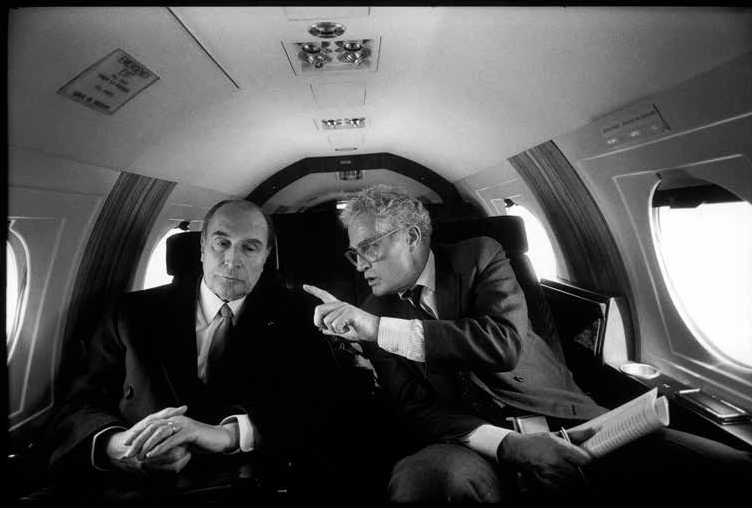

He is not an overtly political filmmaker or photographer, but he defends the rights of peasants, in France as in Chile, Peru and his beloved Africa. Perhaps his most political work has been to document the disappearing rural worlds of his native France. While Depardon doesn’t proclaim his political allegiances, he has been close to power throughout his work. He has photographed all the French leaders from de Gaulle on, including taking François Hollande’s official presidential portrait. There are a couple of remarkable photographs of François Mitterrand and Lionel Jospin, taken on what must be the French presidential jet. But he also accompanied the great Afghan fighter Ahmed Shah Massoud when he was an anti-Soviet mujahideen commander in 1978 and, years later, when he became Minister of Defense in the new Afghan Republic in 1992.

In 1973, Depardon became the director of Gamma, but internecine squabbles eventually got to him and he left in 1978 to join the famed agency Magnum. Tiring of photojournalism, he turned his attention to filmmaking. Depardon’s documentaries were in part extensions of his journalistic interests, allowing him to stretch and enter more intimately into the worlds he explored. He admired Leacock greatly and made his own version of Primary in the mid ’70s by filming the presidential campaign of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. The president-elect took a dislike to the film, even though he had commissioned it, and it wasn’t shown in France until 2002.

Depardon’s work is in many ways closest to that of Frederick Wiseman. Like the acclaimed American documentary director he has been interested in institutions, from his early photographs of a psychiatric hospital on an island in the heart of the Venice laguna (San Clemente, 1982), through his filmed trilogy of portraits of police and health organizations (Faits divers, 1983, Urgences, 1987 and Délits flagrants, 1994), to 10ème chambre – Instants d’audience, in which he filmed daily hearings in a Paris Correctional Tribunal. He is interested in place and his photo book of four years roaming France in a caravan, La France de Raymond Depardon has something of a Wiseman perspective to it.

Since 2000, Depardon has, if anything, become even more prolific. He’s completed a dozen films, including the Profils paysans trilogy and Journal de France (2012), the film version of his four years of travels with his wife and partner Claudine Nougaret, who also gets out of Vietnam, when Salvador Allende was riding the crest of a director’s credit on the film. It’s an intense, affectionate, though distanced gaze at their country. In Les habitants (2016), Depardon is back to his tableau-vivant style, filming face-to-face conversations in a trailer between couples he’s met haphazardly in his travels. His most recent, 12 jours (2017), reveals encounters between psychiatric patients who have been committed to institutions and the judges who must decide whether they are to be interned or released.

His photographic output is equally impressive. Though clearly a master, he is self-deprecating and full of the doubts of the autodidact. And like most masters, he is obsessed and opinionated about his cameras. His apparatus of choice is his faithful Leica (“the fastest camera in the world”); he prefers to use non-reflex over SLRs, and continues to refuse digital (“I’m someone who moves slowly. I’m just beginning to work in colour, so I need more time before trying digital photography…”).

His recent work is dominated by the monumental multi-year project, La France de Raymond Depardon. The book displays 241 photos of France: a single photo taken each day in a different place with an 8×10 view camera. Mostly devoid of people, they are carefully crowded compositions, in which Depardon seeks out unique architectural objects, among them the trademark tabageries, charcuteries, boulangeries and patisseries, and while a few historical jewels and bucolic landscapes make the cut, he is more drawn to urban landscapes and la petite vie: “Deserted beaches bored me, the classical patrimoine too. Little by little, I was heading towards public spaces, lived-in places, the territory.” He says: “I feel confident about anodyne things, banal things, which become universal. I love understated moments…I take a tiny item from page six and put it at the forefront of page one.”

This project allowed him to fully explore colour photography, something he has done sporadically throughout his career, but never with such focus and intensity. Most, though by no means all, of his news photography has been in black and white—more appropriate, he says, to the subjects he was shooting: world events, tragedies, wars. He says b&w is more Manichean, gestural, perhaps fleeting. Colour is softer, more appropriate to the kind of timeless effect he is trying to achieve in this project.

In considering Depardon’s colour photographs, 150 of which were revealed for the first time in a 2013 exhibition entitled Un moment si doux (A Moment So Sweet), he has a clear affinity to brilliant, primary colours, but also soft pastels. He seems hesitant to embrace full realism so even his colour shots tend to be desaturated, with colour becoming a compositional element that often dominates the contents.

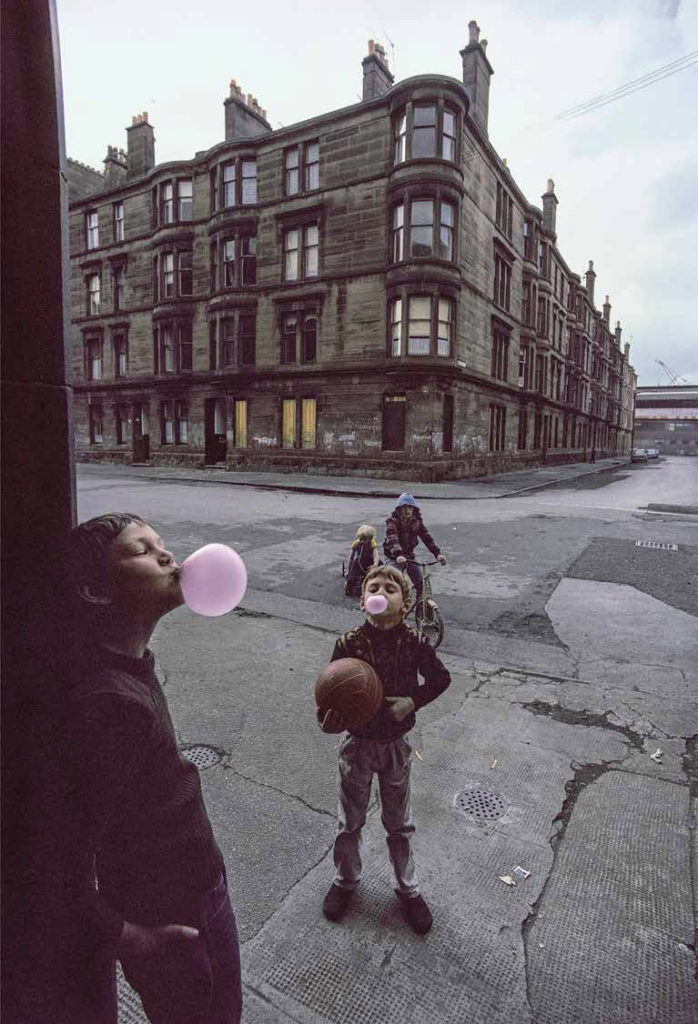

Considering Depardon’s recent works, it is easy to conclude that his view of the world is a wide-angle one. And indeed there is a distinct thread that is characterized by an expansive use of space: exaggerated perspectives, big skies and the smallness of humans in the frame. These qualities are revealed in a remarkable book of photos simply entitled Glasgow. Their story is another bit of Depardonian serendipity. Commissioned by the Sunday Times in 1980 to travel to Glasgow for a feature on Europe’s overlooked tourist destinations, he was instead drawn to districts at the frontline of deindustrialization and depopulation, probably the flipside of gentrification.

Acclaimed by art critics, the photos weren’t published until their release in book form in 2015. There is an almost apocalyptic quality to these images’ wide streets, vacant lots, industrial greys and blacks with brooding skies, sheltering children in billowing pink dresses, blowing pink gum bubbles or pushing tiny prams. Much has been made of the drunks huddled around their bottles and makeshift fires, but the truth is, the photographs capture something much greater and more hopeful: ordinary people of all stripes going about their lives against a backdrop of architectural grandeur.

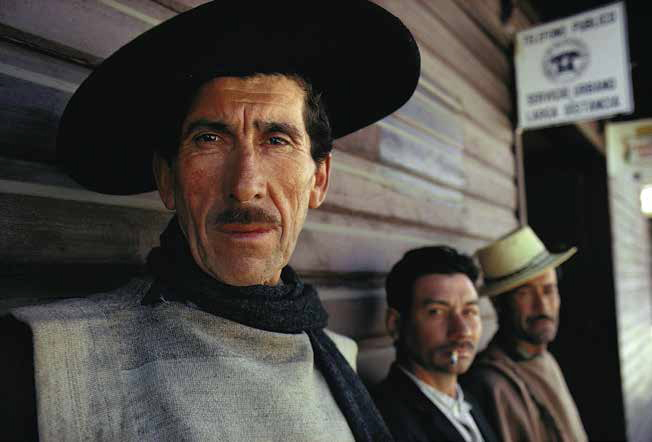

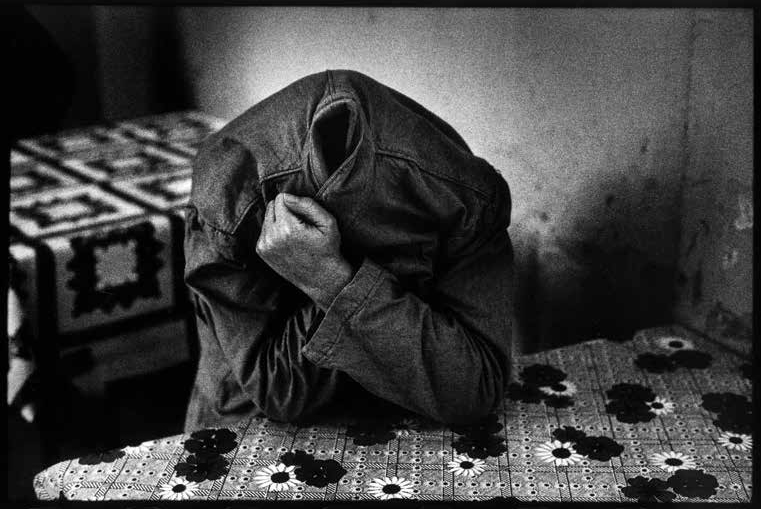

To return to his early work is to be struck by the intimacy of many of his African portraits, similar in emotion to those of the peasantry that form his roots. Depardon’s images are instantly recognizable. After all these years, they still have the awestruck quality of a shy farm boy. He claims that to be a photographer (or a filmmaker) is to be a voyeur. It comes with the territory, he says. In Contacts, his 1990 photo essay of psychiatric patients, reminiscent of Marker’s La jetée, he says in his signature monotone voiceover, “I am a voyeur…I like to watch, I am afraid to watch…The photographer is ready to do anything to obtain his photograph. Or does he suffer as much as his subjects, from whom he seeks to find a self-portrait? He feels his own pain, as well as that of others.”