The following manifesto first appeared in our Spring 2007 issue (#65) with the support of Hello Cool World

Filmmakers must create their own personal manifesto: a world-view, an auteur style, a unique cinematic POV to his or her storytelling. Then, a second ‘world’ has to be engaged. There’s a growing international market which requires expertise in proposals, pitching, marketing, branding ideas, working festivals, schmoozing and distribution. Let’s call it the world media “manifiesta,” a congregation without personal boundaries, borders, national frontiers or technological limits. It’s very competitive and fragmented but filmmakers have to learn how to negotiate a place in it, if they are going to prosper—and survive.

1. HONOUR WHAT ORIGINALLY INSPIRED YOU

My father gave me my first camera when I was seven years old. He was taken away by the Cuban Missile Crisis, so I have always made a psychological connection been camera and family. I try to honour his memory.

People on television protesting against war inspired me. Since then, I have continually questioned everything. People like Mandela and Vandana Shiva have taught me to keep the faith, Sister and my eye on the prize, Brother.

Gandhi taught me that Satyagraha (non-violent resistance) means “Truth-force.” I believe that Documentary is Truth-Telling. At the World Social Forum, Arundhati Roy taught me that: “Our strategy should be not only to confront empire, but to lay siege to it. With our art, our music, our literature, our stubbornness, our joy, our brilliance, our sheer relentlessness—and our ability to tell our own stories.”

2. STUDY FILM HISTORY and ADOPT CINEMATIC MENTORS

I’ve always loved film and images. I continually watch important works in the history of cinema. Films from Fellini, Chaplin, Donald Brittain, Robert Frank. My mentor, Emile de Antonio, was the godfather of political documentary. A man born to fight, he was the only filmmaker to be put on President Nixon’s Enemies List. If there were ever such a thing as a radical army, de Antonio would have been the progressive general leading the alternative media shock troops into a war against oppression. His war was for independent and free expression.

Which brings me to Werner Herzog. Any of Herzog’s 30-odd documentaries would uniquely define the documentary art form. Herzog said: “Perhaps I seek certain utopian things, space for human honour and respect, landscapes not yet offended, planets that do not exist yet, dreamed landscapes. Very few people seek these images today. ”He once told me, “The world is just not made for filmmaking. You have to know that every time you make a film you must be prepared to wrestle it away from the Devil himself. But carry on, dammit! Ignite the fire.”

3. DOCUMENTARY IS AN ETHICAL ENTERPRISE

Aristotle’s book on Ethics is quite useful for documentarians. He wrote, “We do not study ethics to know what good men are like, but in order to act as good men do.” I was amused to find that, in Greek, the words for Ethics, Character and Habit all come from the same root.

Ethics are important in our daily activities, and in all the processes used to create or consume media. There has never been a film that does not raise ethical questions. Ranging from who’s paying for the film, through to questions about the relationship of the filmmaker to the subjects during shooting, through to editorial manipulations and marketing, ethics raises its lovely head. This is why I love making movies.

4. DOCUMENTARY MEANS MEDIA LITERACY

Literacy is the ability to understand, analyze, critically respond to and produce texts in different contexts. Media is as ubiquitous as the water we drink. It is the language our children speak. In a world where media is the very air we breathe, we need to expand our view of literacy to include media literacy. We must understand what media is, what it does and how it works.

And how to make it ourselves: how to “read” and “write” with light, in a world where the pen is now the camera, where the writing’s on the wall—in the form of a screen. Any screen, anywhere.

5. LIFE IS POLITICS

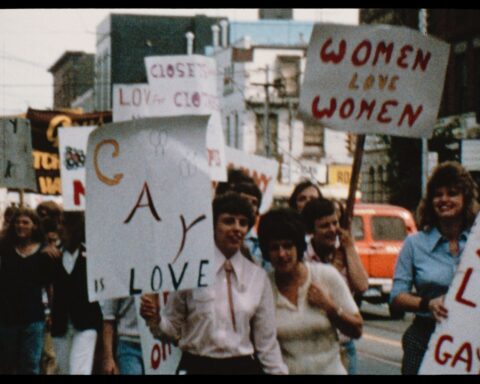

We live in a political world. Like all artists, documentarians owe it to the future to speak out against injustice wherever it may lie. Lie is the operative word of this age. We are now, have always been, and always will be, at war. It is a war for human minds, and their active will. Independent thinkers, documentary filmmakers and digital media artists are the foot soldiers of this media war.

We should attempt to pour our work and activism into the forge of human service. Let us become our own masters, re-appropriate our media away from conglomerates, consumption and mass-mind colonizers. Let us “robin hoodwink” them, transforming our documentary artwork into real media for the masses.

6. DOCUMENTARIES CAN CHANGE THE WORLD

Communication is a fundamental human right. MediActivists are working worldwide with their digicams in front-line trenches, defending individual rights, defining the collective rights of the communities, and protecting all our rights. The communication of rights and the right to communicate is at the heart of democratic social struggle. It is for greater digital dialogue, pluralism, tolerance and participation. The digital documentary revolution is about audiences becoming “prod-users,” i.e. producer-users, instead of passive receivers. The digital dream is now a practical reality. Armed with information, the world can change.

7. CREATE THE FUTURE

Documentarians must embrace the new technologies. We can take what we know about traditional documentary and fuse it to what’s great about new media, next media and now media. For Generation D (as in Digital), living in the Digi-age, the documentary is being reincarnated as the digital Document. One which may embody elements of fiction, reality, animation, graphics, cyber-text languages, audio, TV or games design. Content for all platforms and delivery systems. In our new world, definitions dissolve, new forms emerge. They are about blend, mash, trans-boundaries, transgressions and trans-genres. They expand the language of acceptable cinema. Screen culture can bring reality and poetics to the public, interface to interface. It provides absolutely essential information needed to sustain the future.

YOUR FIRST STEPS: THINKING LOCALLY IN THE GLOBAL FIESTA

Armed with your own manifesto and having started to make point-of-view films, where do you go? Reversing the words of the eco-wise: You must think locally, and act internationally. In other words, be “globalocal.”

Once you’ve done that, you’ll attain international documentary stardom. Satisfaction Guaranteed! You’ll enter the stream as an international player in the documentary “manifiesta,” which is a combination of business, marketing and hard work, tempered by the odd celebration.

In my cosmology there are four stages you must master. You must write the most original proposal ever written, you must pitch it perfectly in the marketplace, you must go make it as best you can, given your always limited resources and finally, you must get the film out there. Really out there. Only then can you reap your just rewards, a few golden statues and a few honourable mentions.

STAGE ONE: THE IDEA AND PROPOSAL

Making documentaries is like falling in love. The first stage comes in that beautiful moment when you think up an idea for a film. It’s like spying the muse across the room. Love at first sight. But is it the Ah Ha! moment or just another Ha Ha Ha? It comes across the room. You rise to the occasion, embracing the idea. But then, the subject of your desire slaps you in the face. Another great idea shot down.

You have to keep a cupboard filled with ideas. Your filing cabinets should be bursting. A little clip here from a newspaper—you do buy newspapers, don’t you?—or snippet from the web can pique your interest, reinforcing your unique point of view. You must conduct research every waking and every sleeping moment of your life. But you have to become so obsessed with just one idea, choosing one out of your litter of a thousand fuzzy animals. You must be prepared to run with it for a year or two, spending time and money and energy, with the full knowledge that there is a ninety percent chance that you won’t make the film, for hundreds of reasons. You also have to work on six other great ideas at the same time. One might be in editing, another might be shooting, one is in development, a few are wish-listed, while the others will die on the order paper.

Given all that, you still have to believe, and then you will. I strongly suggest that you do market research. See what other films are being made or are already out there before you waste your time. At IDFA (International Documentary Festival Amsterdam), they get over two thousand entries every year. And those are the more important, social and political feature and medium length docs, not everything produced each year, which numbers in the tens of thousands. You have to be unique, and have unique access. In these interNETional village days, where research is just a click away, all potential stories are out there, within reach of any filmmaker’s brain. So think obscure, think exclusive, think “globalocal.”

Never take development money from anybody. Go for full financing right away. Or start shooting without any money. It will come. Taking development money usually is a way for the financiers to bide their time and hedge their bets, and keep pesky filmmakers busy and out of their hair. Broadcasters are developing far more projects than will go to air. Someone has to lose.

You have to invest in your own research travel. To the ends of the Earth. A friend of mine went to investigate a potential film about a very obscure poet in Central Asia. When she reached the poet’s remote mountain village, there were already two other film crews there, vying for rights to the same story. Do your research first. Granted, there are only seven film stories ever told in this world, or perhaps only two: time and memory are the only subjects of every film. But broadcasters and distributors have memories better than the average cell phone battery. They know what films are in the Zeitgeist. Ask them.

Never go with the trend. Study television. Download the grids and channel guides for international broadcasters. See what they’re looking for in the producer sections of their websites. You can be sure that if you see a new tendency on television towards a form or theme in documentary, that it’s already too late for you to emulate it or think about supplying a similar clone into the (main)stream. Programming needs are filled at least a year in advance. You have to think two or three years ahead. That’s how long it takes to make a serious documentary. Learn how to write words down on paper. Use a spell checker. Better yet, hire a writer. Filmmakers are not necessarily good writers. Nor the best people to pitch-perform their projects. In the old days, I would love to write dozens and dozens of pages for my average proposal. Some of the backward-looking film agencies still require this. My theory is that the person who initially supports you at a funding agency or broadcaster might be prepared to read all you write. But their boss or head of department will need only a one pager, and that boss’s boss will only need a paragraph. By the time it gets to the top of the film-food-chain, the CEO will only need the one-liner, the five words that might appear in a television guide. Be prepared to work for a year to reduce everything to less than a haiku poem. (As in… A great film about great film.)

What funders, agencies and international commissioning editors want, in terms of paper, are clearly articulated, succinct paragraphs. You need to encapsulate your proposal into a simple synopsis written in Basic English. You should include brief examples of a treatment or visualizations, short bios, filmographies and a budget top sheet. You also have to know how to package your words with a modicum of graphic flair, incorporating photos and visuals. Filmmaker, know thy graphic software.

You are selling your idea, but more than that, you are selling your passion. In the end, the only goal of a proposal is to get you to a second meeting. To follow-up in conversation, either live, or teleconferenced, so both you and your potential funder can assess each other, and each other’s needs. This is where seduction comes in.

Once you’ve written the ideal proposal, send it around the world in eighty days. You can mass-produce it in colourful, unique pamphlets, one sheets and even standard typewritten pages. Hard copies and e-mailable PDFs. A good proposal has to be adaptable. One international funder might want a certain thing, another domestic broadcaster wants something completely different; often, they’re really the same, but written differently. You have to revise your ideas, shift emphases, rewrite. The producer in you has to reconcile all those differences, use diplomacy and still get what you want.

So, your proposal is out there. You could hire a call centre in Delhi to cold-call potential funders, or send them unsolicited e-mails. I wouldn’t advise this. Your potential masterpiece could be considered junk mail. I once sent a proposal letter by snail mail to every public broadcaster in the world. I got back three positive responses. One of those was from a small, remote island country, which had a national broadcast authority, but as yet, no television sets for its citizens. They liked the idea, though. Mark Achbar and I sent out 1,500 generic proposals for our Chomsky film, Manufacturing Consent, to every possible foundation in the US. We received only a few positive replies. So, instead of a blank blanket approach, it helps to get a more experienced filmmaker to endorse your project and introduce you. Face-to-face is the only real way to sell yourself, and your film.

STAGE TWO: PITCHING AND FUNDING

How do you get the money for your great idea? Well, you can beg your family, approach charities and hold Internet fundraisers, as US filmmaker Robert Greenwald did for his recent Iraq film. You can work the arts grants, government agencies and NGO’s. Or seek solace, and alms, in television. For the standard one-hour social documentary there are about forty public service broadcasters still left in the world. There are also hundreds of digital, over the air, commercial, direct to home, satellite, specialty, cable and Internet channels. Know thy friends, and thine enemies, too. All broadcasters tend to hang out at MIP, the International Program Market in the spring and fall of each year in Cannes. It’s a gigantic flea circus market of everything broadcast and other-cast in the world. Places like Cannes are hard to fathom, but you can latch onto delegations from your area and go along for the schmooze.

But it makes more sense for documentarians to hang where the doc money people go. This means the Forum at IDFA in Amsterdam, France’s SunnySide of the Docs in La Rochelle, Hot Docs in Toronto, Silver Docs in Washington,D.C., the U.K.’s Sheffield Docfest, the AIDC (Australia International Documentary Conference) and a handful of other meet-me-markets, where you can eyeball and buttonhole people. You have to be prepared to get any place and every place in the world for these essential project development markets.

Be prepared to pitch your ideas privately and publicly in front of a crowd. You have to become gladiators in front of a gang of TV emperors whose thumbs, and souls, are generally held down by gravity. Not to mention their pocketbooks. The IDFA Forum was a pioneering project pitching initiative and leader of the first documentary funding revolution. It was conceived as a meeting place to develop networks of cooperation, contacts and expertise between private filmmakers and public television systems. The first years were full of excitement and new encounters. The original proposal pitches were exciting, dynamic, creative, collegial and innovative happenings. The early Forums also developed into real places to do business. The films themselves were the main focus, rather than broadcasters’ timeslots or a specific network’s message to the world.

Since the birth of formal public pitching for documentary almost two decades ago, seemingly identical funding systems have replicated themselves around the world in a constellation of very similar entities, functioning at doc-markets, festivals and forums. They have evolved into a competitive, adversarial system, created to make good product. You need to observe them in action. You need to join the fray.

There have been countless individual success stories. There have also been as many critiques of the different pitching systems as there have been commissioners, producers and filmmakers to make such complaints. Today, with over 40 such forums all over the globe, there is a groundswell of criticism, which posits that the Commissioning Editors have became the driving force and, some would say, the show itself.

Yet most producers and financiers have a love-hate relationship with the process. They take a “You can’t live with it, you can’t make a living without it” attitude. Once upon a time, the 45 or so new projects pitched at each of the main forums around the world may have been enough. But thousands of social documentaries are made every year now, and there are not enough slots in the pitching systems, nor on conventional broadcasting grids to accommodate even the most worthy ones within traditional, linear ways of thinking about programming.

Now is the time for doc makers to look at new ways of funding non-fiction. One thing that is sure: a hyperflow of technological advances is accelerating changes in the production, distribution, broadcast and netcasting of documentary and factual film. Docs are morphing into the nether-ranges of edutainment, and next media. We are entering a world where Peer-to-Peer (P2P) video-pod casting (vcasts), DVDocs, inter-netional docitizens, wireless mobile reality, multi-(plat)form digidocs, VODocs on demand and wikidocs will become part of the standard grid.

Viewing habits are changing rapidly, audiences are migrating, in large flocks, away from the conventional broadcasting. New opportunities have opened up for documentary makers. Pubic television is re-inventing itself, moving toward models of public service publishing.

I would look to financing my social documentaries and other signature factual films with a worldview that included words such as Public Private Partnerships, crossmedia funding, social entrepreneurs and Public Service Publishing in my lexicon of speculative non-fiction.

STAGE THREE: MAKE THE THING

Recently, I wrote a set of rules of shooting for younger filmmakers, as a tongue-in-cheek meditation. Among my principles were: “No hairs in the camera gate, shave your head before shooting; focus, then focus again; you will throw out the first ten minutes of the fine cut; do not interview anyone in chairs; remember to listen to people.”

I won’t spend much time on this stage. Let’s assume you’ve made a few films, taken the right courses and professional development seminars and read all the manuals. That would be my advice. Read the manuals for all of your equipment. Then practice, and practice some more. Practice on short films. Practice on other people’s films. “Just Shoot, Shoot, Shoot,” as my film master Ricky Leacock told me.

OK. You’ve made the best damned film you can make, at this particular time in your life, exhausting all of your financial and psychological resources. And it’s an original tour de force.

STAGE FOUR: MARKETING

Now that you’ve made your masterpiece, how do you pass it on? You have to learn everything there is to know about distribution, marketing, festivals and the selling of your Faustian film soul.

Learn how to emulate Hollywood. Test market your films before they’re finished. Don’t think that anything is unchangeable or precious. You have to be prepared to work long and hard for as many months or years in the marketing of your film as you did writing, pitching and making it. Like Hollywood, you have to invest as much money, or sweat, in marketing, as the shooting budget.

Or, you have to learn how to be a bare-foot publicist, marketing yourself and your movie with few or no resources. This may mean learning how to beg favours. It may mean getting into gossip columns or editorial pages rather than paying for ads. Learn how to use viral marketing. YouTube or Democracy Player may be the most effective way to market you and your films.

For marketing and publicity purposes, your film needs a consistent look. Work with artists to develop a logo, a typeface, a style. Make a trailer. You can re-purpose the pitching video you should have made earlier to sell your idea. Write great copy and press kits. Above all write the perfect 200-word synopsis. When that synopsis gets used by a journalist or in a film festival catalogue, it will be set in stone. That description will be the one that all subsequent festivals and writers use as a basis. Choose your words very carefully. Control everything you can at this stage.

Design posters and graphics that are clean and bold, with big, big super-size type. In a film festival, your posters may be competing with the visual pollution of 600 posters of other, obviously less worthy films. Remember you want your poster to be the one that people steal right off the wall at the end of the festival.

Festivals are everything and nothing. There are, at my last count, 2600 festivals in the world. There are A, B, C, D and Z list fests. You don’t have to enter them all. Never enter a festival that charges you money. You might want to charge them. There are a few dozen important festivals for the documentary genre, including most of the major international fiction festivals.

If you are lucky enough to be invited, hope that they pay your way. Otherwise, get public agencies and embassies to fund you. Figure out if you can do ancillary lectures and workshops. Always volunteer to be on festival panels. It gives you, and your project, visibility. Have something witty or contrarian to say.

At festival cocktail parties, stand near the service entrance. That way you will get first crack at the hors d’oeuvres, and keep your expenses down.

Make sure you have a complete, professional press kit. And correctly labeled and beautifully packaged DVD press copies. Always take at least four great photographs on location, which can be used in marketing.

Deal with the press like you would deal with a friend. Respect them. Share their cynicism. Don’t be over-eager. Provide them with an angle or an angel, a character who gives good copy. Be articulate, at least for a few moments. Sit up straight when being interviewed. In the early stages of your film’s distribution life, make sure you get those important positive reviews in the key industry publications: Variety, Screen International, Cahiers du Cinema, the Hollywood Reporter and their non-fiction sisters, DOX, Documentary, Real Screen, etc.

Learn how to blurb even the most mediocre reviews into ringing endorsements. A seven star review from the Dubai Daily Planet is worth its weight in gold. Add all of this favourable praise to your growing press kit.

Always treat a festival’s volunteers with grace and politesse. Thank the programmers and festival directors for inviting you. Do everything they ask you to do. Never act out, make pushy demands or think you are any more important than the lowliest of the lowest short filmmaker in the group. All filmmakers are born equal. Some are marketed better.

Use festivals to garner key reviews or meet the public. Never miss a Question & Answer session. You can use festivals to get invited to other festivals. A great screening and discussion will help you sell your film in the domestic territory where the festival is held. But mostly, you can use festivals to find international sales agents, distributors, broadcasters and secondary markets for your films.

There are only a handful of excellent international sales agents for documentary in the world. Their job is to sell your film to distributors, whether they are TV broadcasters, theatrical distributors, other exhibitors or digital labels disseminating your work in other forms, media and territories.

I would not advocate for self-distribution. You’ve spent half a normal person’s lifetime making the film. Do you really want to spend the rest of your days searching for elusive, multiple markets? That’s why they call them agents. I’m of a mixed mind on this question. There is evidence that a properly nurtured, self-financed distribution campaign can bring more revenues back to you. But it’s work. And it takes a lot of time, which you could be spending making more films.

It helps to keep as much of the money and rights as you can for yourself. But in the end, you will have to share it equitably with the distributors.

We all read about how documentary has made great inroads into the theatrical distribution market. But when you analyze the figures, no more than a handful of feature-length docs really make their money back each year. It’s been like that for two decades. These are hard times for art films of any genre. Theatrical distribution can add to a film’s reputation and long-term success though. With companies like Canada’s FilmsWeLike, for which I am an unpaid advisor, and many digital cinema initiatives throughout Europe and US rep cinema runs, you can start to break even. Which is better than Hollywood, or the domestic fiction scene, where 9 out of 10 films fail.

The numbers in theatrical distribution are frightening. In the simplified version, the exhibitor, the person who owns the cinema or venue, takes their fifty or sixty percent, then the costs of print and advertising are taken off, the distributors gets their cut, and they turn what’s ever left back to you, which you turn over to your equity investors. This may mean that in the end, you get five or ten cents back on the box office dollar. And that’s on a good day.

So, it’s the international DVD sales, and Vpod downloads and broadcast sales, which hold the most promise for docmakers, and the most royalties. Learn how to make distribution part of the production picture. Engage distributors early in the development of your idea.They may even pitch in some money to make the film. You must learn how to overturn the tyranny of length. And you’ll have to manage digital rights within the new technological context, including the mastering of concepts of copyright, licensing, windows and the ongoing dissemination of documentary across new platforms, territories and time.

After that, its good luck and timing. No one in the world has the perfect formula for a film’s success. Or what the public wants. It’s been the holy grail of filmmaking for 112 years. Your guess is as good as theirs. But as long as you keep your manifesto in your mind, and in your heart, you won’t go wrong.

In the future, perhaps what we can all look forward to is the Dokumat 500, which is a human-free, fully automated, all-in-one documentary robot I found on the Web. It’s described like this: “Dokumat is a fully automatic documentary robot. The Robot consists of a modified tripod and a video camera. The tripod moves autonomously around and pans and tilts the camera. It switches the camera and a spotlight, mounted next to the camera independently on and off. So, the documentary videos are edited directly inside the camera and the robot supplies a complete finished end product. All you have to do is switch on the device and insert a cassette.”

But until the time that all filmmakers are replaced by wonderful, artificial intelligence, let’s celebrate documentary as the mutual reflection of the wild world’s harsh reality and our own impressive, human creativity. In the end, thinking off the grid of dominant ideas, you’ll have to develop your own manifestos, your own pathways and your own “manifiestas”—in a new world that only you can master.