What is a feminist film? This question can cause confusion when it comes to reflecting on the history of filmmaking that’s been labeled as such, given that the definitions will vary depending on whom you talk to. While this poses a problem for conventional notions of history (which, like so much of the Western literary canon, tend to demand a sole author, a victor and a neat conclusion), it does open up possibilities for re-thinking what is gained from looking back on the history of films directed by and about women in Canada.

The 1970s is a good jumping-off point for this discussion, as this was the moment when feminism sprang into the world as a political and intellectual movement. And in the Canadian context, this means talking about the National Film Board’s Studio D. As Kay Armatage, a professor at the University of Toronto and co-editor of Gendering the Nation: Canadian Women’s Cinema, put it: “There were women making films [before the 1970s], but there was nothing that specifically addressed itself to feminism. When Studio D was formed, you had an active stream of films that were about the women’s movement and declared themselves part of the women’s movement.”

A result of a “catalyst moment,” as Armatage calls it—while also being a product of decades of work by women in film—in August 1974 Studio D became the first publicly funded women’s film production unit in the world. This was the heyday of second-wave feminism—a year before the publication of Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay The Female Gaze (though it was written in 1973), two months before the Equal Credit Opportunity Act was enacted in the U.S. and two months after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Corning Glass Works v. Brennan deemed paying women lower wages unjustifiable. These historical forces impacted Canadian feminist thinking, and thus Studio D. As Lynne Fernie, co-director of Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives (1992), said: “Second-wave [feminism] was much more an American cultural notion and Studio D was locked into that.” It’s a crucial point to dwell on, as it points to a tension that often comes up in discussions around Studio D’s history, arising from the fact that, as Armatage neatly puts it, many of the films were “specifically addressing white middle-class women.”

Far more in-depth discussions of Studio D have been printed elsewhere (see, for instance, D is for Daring: The Women Behind the Films of Studio D by Gail Vanstone and Bonnie Sherr Klein’s Not A Love Story by Rebecca Sullivan), and there’s not enough space here to dig into its full history, first under Kathleen Shannon (1974-1986) and then under Rina Fraticelli (1987-1996). What can begin to be explored, however, is Studio D’s legacy. But to begin to ask these questions does require a brief overview of Studio D. (Acknowledgement here goes to Elizabeth Anderson’s comprehensive chapter in Gendering the Nation.)

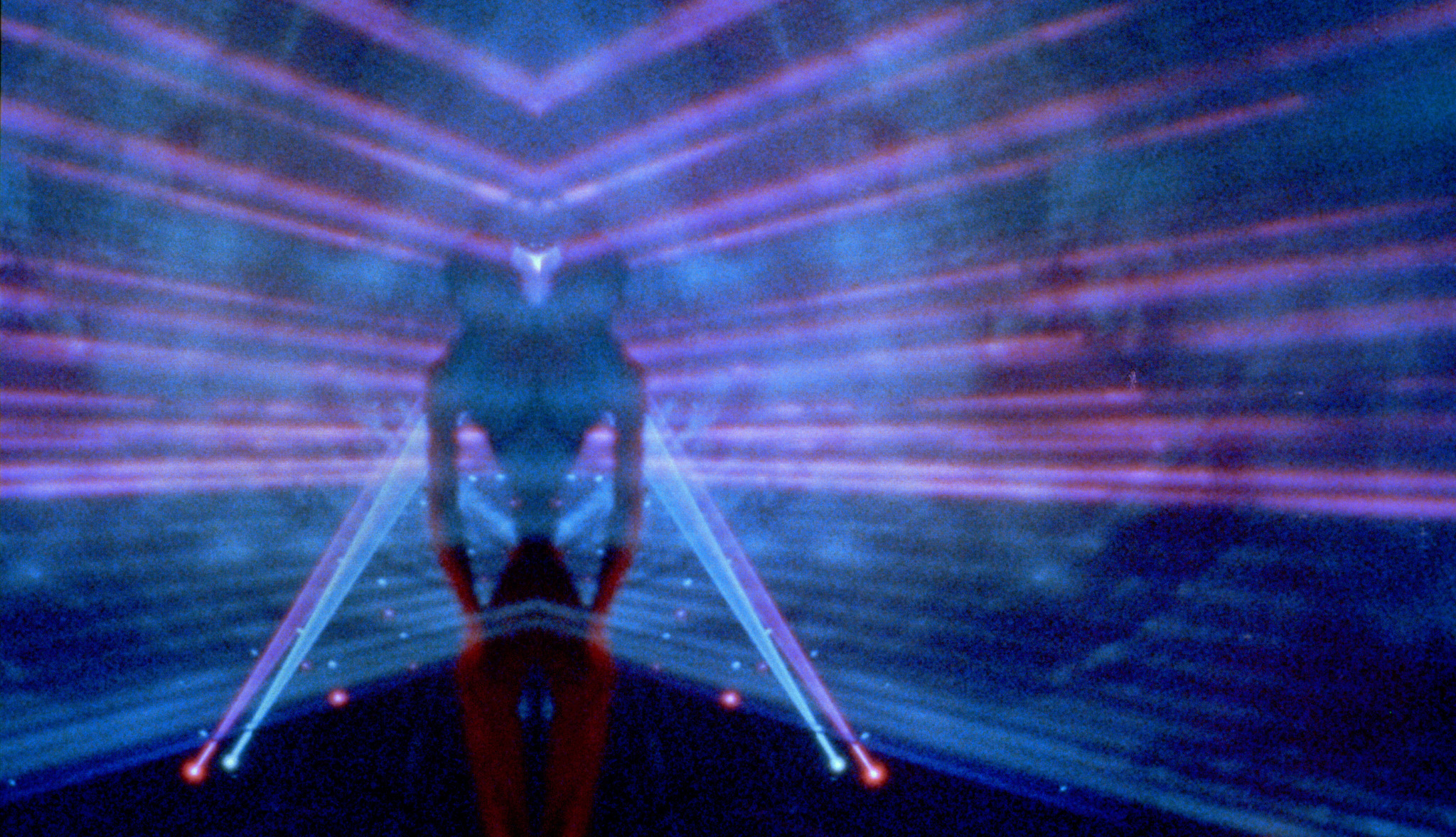

Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives, Lynne Fernie & Aerlyn Weissman, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives, Lynne Fernie & Aerlyn Weissman, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

“I do see filmmaking as having phases and they are connected to political movements,” says Fernie when asked about shifts she’s seen in feminist filmmaking. It’s a comment that’s deeply pertinent to looking at the impact of Studio D, which, drawing on the NFB tradition, produced many social realist docs, described by Anderson as: “talking heads and voice-over narration, they were didactic in tone.” While this tendency was a product of the institution, Armatage notes that Kathleen Shannon “had very specific ideas about what feminism was, how films should be addressed and what issues should be addressed.”

This isn’t to dismiss the work done by Studio D during this era, which included Great Grand Mother (1975), Patricia’s Moving Picture (1978), Some American Feminists (1977) and the controversial Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography (1982), but rather to point to the idea that Studio D doesn’t necessarily need to be used as a benchmark for all Canadian feminist doc-making. It also points to the reality that while Studio D gained greater funding and recognition for being part of an institution, it was constrained when it came to taking formal or topical “risks,” like breaking away from the straight-up doc form or telling stories about (and more importantly by) queer women or women of colour. (It should also be noted that Studio D was operating in English-language Canada, and thus the Francophone feminist filmmakers, like Léa Pool, Sophie Bissonette and Anne Claire Poirier aren’t always part of this conversation or history.)

But, returning to how politics informed Studio D’s outlook, this more limited scope was not just the result of institutional constraints; it was also a product of the feminist movement of the time. This began to shift in the 1980s when writers and activists began to publicly examine how issues like sexual orientation and race impacted feminism—especially with the publication of books like bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman?: Black women and feminism (1981) and Angela Davis’ Women, Race, Class (1983). Fraticelli, when she took over as head of Studio D in 1987, also responded to this landscape by attempting to make “structural framework” changes regarding inclusivity goals, such as New Initiatives in Film (NIF). Running from 1991 to 1996 under the direction of Fraticelli and Sylvia Hamilton, NIF’s aim was to, as Anderson writes, “address the under-representation of Women of Colour and Native Women in Canadian film.” This saw the studio commissioning of works like 1991’s Sisters in the Struggle (Dionne Brand and Ginny Stikeman) and Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman’s queer-centric Forbidden Love.

But complicating this history is that, at the same time that Studio D was in operation, filmmakers like Alanis Obomsawin and Jennifer Hodge de Silva were making films—also at the NFB—that questioned a cohesive multicultural Canadian identity by turning their cameras on Indigenous socio-political concerns and issues being faced by Black Canadians, respectively. In this way, inclusivity at Studio D was both an issue of structural power and one of feminist political aims. Which brings us to intersectionality.

Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, the term intersectionality challenges “the tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.” For instance, while those aforementioned 1970s court cases resulted in rulings in favour of women’s rights, Crenshaw points to a lawsuit filed against General Motors in 1976 regarding mass layoffs of Black women in which, because GM had hired white women for years, it was ruled that “no sex discrimination…could conceivably have perpetuated.” As Crenshaw shows, rulings like this make white women’s experiences the benchmark and overlook how women of colour are impacted.

But how does intersectionality play out when thinking about feminist film history? One way of looking at it comes from Danis Goulet, a film director, programmer at the Toronto International Film Festival and former artistic director at imagineNATIVE. “I can’t imagine a feminist cinema without talking about Alanis Obomsawin,” says Goulet. Of course, Obomsawin had been working at the NFB since well before the creation of Studio D, and continues to make films now, often investigating the impacts of Canada’s legacy of colonial violence upon women and children in Indigenous communities. (A point that, in an issue motivated by Canada 150, can’t be emphasised enough.) “Her concerns are in a different context, which becomes about intersectionality,” says Goulet, who also states: “In the history of Indigenous cinema, women are the grandmothers. They are the drivers.” Put another way, issues of colonialist history are feminist ones as well, but since they don’t impact white women, they can tend to be erased or—ironically, given how often this happens to women’s cinema—dismissed as niche.

If we’re to move towards a comprehensive history of feminist documentary in Canada, it will be necessary to look beyond the issues that have been codified as feminist since the 1970s. In this regard, Hodge de Silva also bears noting here. Writing on her 1983 documentary Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community, which looks at the relationship between the police and the community—especially the Afro-Caribbean one—in Toronto’s Jane-Finch Corridor, writing in Gendering the Nation Cameron Bailey points to how it “service[s]…consolidating national unity and resolve in the service of dismantling, or even questioning, an oppressive status quo that may in fact stem from the construction of ‘national unity.’” Though the doc is not as radical as some may like, the Toronto Police Board still tried to impede public screenings and also its broadcast.

The inclusion of a chapter on Hodge de Silva’s work in Gendering the Nation points to how work to rewrite the Canadian feminist doc-making canon is already underway. But the fact that Bailey remains one of the few people to have written about her work also suggests we have a long way to go. That said, the current generation of feminist filmmakers has an inspiring crop of women to turn to. Ella Cooper, the founder of Black Women Film!, a leadership program dedicated to mentoring Black women filmmakers and visual artists, points to Ngardy Conteh George, Tiffany Hsiung, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, Allison Tuk and Iris Ng as folks who are inspiring her. Cooper also has a crucial reminder for feminists in film: “It’s still so important to get women in the director’s chair that we can forget to look for the spectrum of culturally diverse and trans women”—a reality that means “there’s still a racial divide in film.”

Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community, Jennifer Hodge & Roger McTair, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

As for what’s next, solutions will need to be multi-fold. First, feminism’s continued shift towards intersectionality will entail a widening of what “counts” as feminist film. “I think there’s a confusion that feminist filmmaking is only about ‘women’s issues,’” says Cooper. Fernie speaks to a similar point, noting that, “Definitions are helpful but shouldn’t be a Bible, otherwise feminist filmmakers can only work on women’s issues.” Or, as Goulet neatly summarised it: “White men and their experiences get constantly reaffirmed. Feminist cinema is the opposite of that.”

A second point, which Armatage is keen to emphasise, is that we have to reform funding structures. In 2016 the NFB declared it would achieve gender parity in its productions (on the heels of Anna Serner at the Swedish Film Institute reaching this goal). Telefilm has tried to follow suit, but to fewer accolades; as Armatage notes of the governmental funding agency’s language, “there are no commitments. It says ‘parity,’ but not parity of what. For example, how do you define women’s projects? [In other countries], you have to hit three of producer, director, writer, protagonist, editor.” Without clear-cut rules, there’s wiggle room that allows for institutions to slip back into the current, unacceptable status quo.

Lastly, we have to consider not just which films are getting made and by whom, but also ensure that they’re getting covered. “There’s a huge gap on people writing about feminist filmmaking,” says Armatage, meaning that what ink is given to this area shouldn’t be given lightly—a point that’s weighed heavily on me in writing this piece. Given this, the imperative radical, feminist act is stating that history isn’t finite and has multiple authors: as feminism continues to evolve, its history needs to keep being re-written in order to continue to champion the voices that refuse to go quietly into the night.

Correction: The print version of this article features quotes attributed Kass Banning. All citations by Banning should be attributed to Kay Armatage, Professor at the Cinema Studies Institute and the Women and Gender Studies Institute at the University of Toronto. Armatage and Banning are editors of Gendering the Nation: Canadian Women’s Cinema, published by U of T Press. POV apologizes to both Armatage and Banning for the error.