Cinephiles searching for air conditioning this summer can get ample bang for their buck thanks to the Toronto International Film Festival’s new Frederick Wiseman retrospective. The TIFF Cinematheque series, curated by POV contributor Vivian Belik, lets audiences cool off with classic works by the director famed for his three-hour running times. Audiences who came to love Wiseman thanks to recent hits in the TIFF Docs slate like Menus Plaisirs – Les Troigros (2023), City Hall (2020), and National Gallery (2014) won’t want to miss this expansive offering of the director’s formative works.

While Wiseman’s most recent docs aren’t playing in the series, Body Politic gives a rare chance to see newly restored films in the director’s oeuvre. These selections are canonical works in America’s independent documentary movement. “Wiseman’s cumulative body of work has been likened to the Great American Novel in that it ambitiously deconstructs the social and political fabric of the United States while honing in on the complex and often contradictory nature of human behaviour,” writes Belik in her programming notes for the series.

Wiseman’s observational form remains a key branch of cinéma vérité as the movement shook up the ’60s. His works—even the quicker earlier ones—bide their time by observing people in institutional settings. His docs capture the machinery of human life as everyday people—labourers, patients, patrons—frequent places that fuel their days: schools, hospitals, libraries, and theatres, among other venues where stories collide.

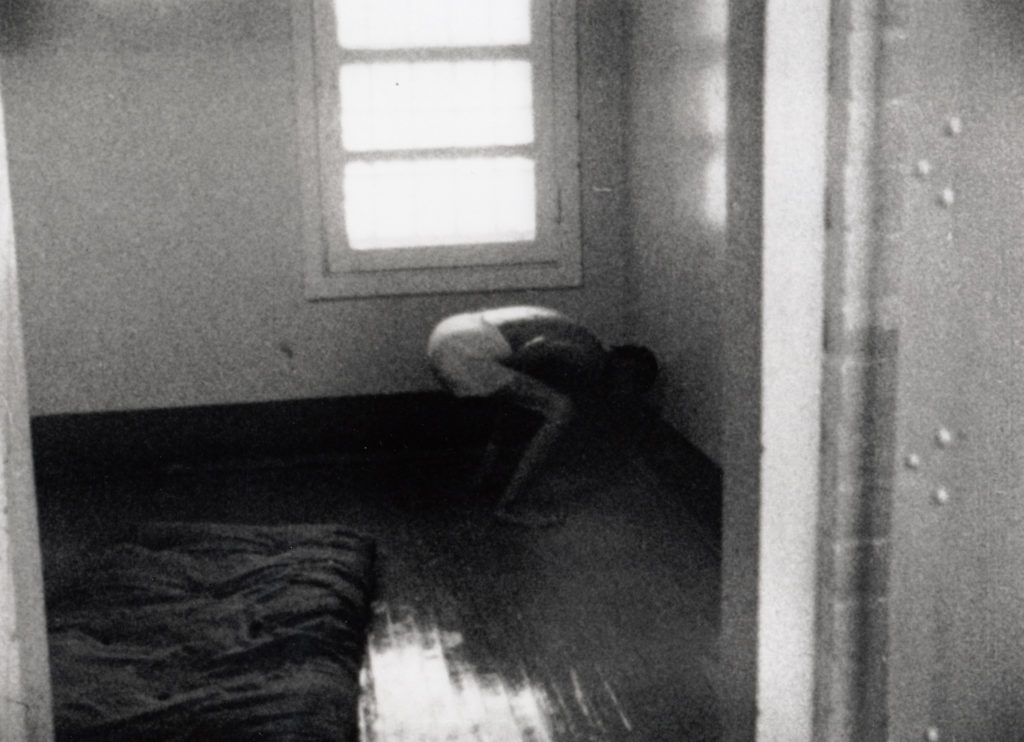

A must see among the series may also be the most widely screened work of the retrospective: Titicut Follies (1967). The documentary, Wiseman’s first feature, remains as significant as ever for its groundbreaking glimpse into a correctional facility for inmates with intellectual disabilities. 50 years ago, Wiseman’s camera toured the halls of Bridgewater State Prison for the Criminally Insane and introduced audiences to Jim—an all-timer of a documentary character whom the film defines not by the events that brought him to the facility, but through the subtle humour that gets him through the passing days.

“A young law professor at the time, Wiseman got the idea to film a documentary at Bridgewater while taking students there to observe how a state mental institution worked—or didn’t, as the case may be,” Geoff Pevere wrote in an essay on Titicut Follies for POV #107. “He went through what he thought at the time were the proper channels, requesting permission to film inside the facility and agreeing only to shoot when he was given a verbal okay by the staff. It was they who determined whether a subject was fit for filming by Wiseman, they who held ultimate power over whether or not the treatment of a guy like Jim was suitable for public consumption. And they decided it was, at least until somebody higher up actually had a chance to see Titicut Follies and be suitably and reasonably appalled. Nobody in the film looked nearly as bad as the hospital and its staff did, and nothing in the film made the hospital and its staff look quite as bad as Jim’s morning shave, shower and liquid meal.”

Titicut Follies faced considerable hurdles upon release and was very difficult to see for years, but the documentary field should give Wiseman a nod of thanks for not throwing in the towel. (A 1991 Supreme Court ruling helped the film reconnect with general audiences, while a spot in the 2015 TIFF Cinematheque selections helped bring the doc local interest for another generation.)

Not giving a toot whether his film ruffled the establishment’s feathers in the service of public good, and finding power in difficult images to challenge the status quo, marked a key experience for a filmmaker with a sense of using documentary for public good. But Titicut Follies equally heralded an artistic eye, which is one reason why it stands the test of time whereas other docs from the era have largely been forgotten as dated institutional works. Add 50 years of political correctness to the language and practices the film observes, and it really stings today.

That fine and empathetic eye for observing the incongruity between places like Bridgewater that sought to provide human care and the absence of humanity within the institutional operations would define Wiseman’s early work—and later films in a career that was going strong as the director was well into his nineties. (In February 2025, the 95-year-old Wiseman suggested that 2023’s Menus Plaisirs might be his last work given the energy involved with making films.)

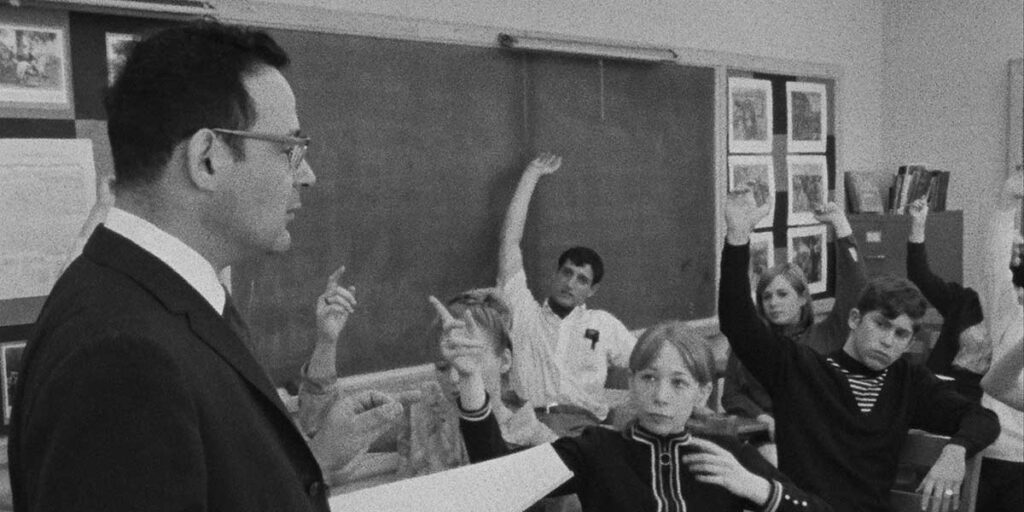

Titicut Follies set promise on which Wiseman handily delivered. His subsequent features High School (1968) and Law & Order (1969), both screening in TIFF’s retrospective, brought a similar lens to Philadelphia classrooms and Kansas City cops, respectively. Both docs endure as significant observational works of the era. They demonstrate a confident vérité approach to human interactions within established frameworks as teachers engage students with course syllabi and officers interact with citizens to facilitate the orderly function of daily life. The latter doc won Wiseman his first of three Emmys in a career that saw few accolades before Fred’s Lifetime Achievement Era. The other two Emmys were for his extraordinary Hospital, which took his vérité eye into the New York’s Metropolitan Hospital to consider patients and doctors alike. (Hospital screened this past weekend in the retrospective.)

But for all the time that Wiseman gives audiences to marinate in these environments, don’t make the mistake of calling his observational docs fly-on-the-wall portraits. “Most flies I know aren’t conscious at all, and I like to think I’m at least 2% conscious,” Wiseman told The Guardian in 2018, humorously noting that he found comparisons to a housefly insulting. “I come across this thing as a matter of chance, and maybe occasionally good judgment. I take the risk of shooting it because I think it might be interesting – then my job as an editor is to decide what it is saying, whether I want to use it, in what form, and where I’m going to place it.”

Having more discerning taste than a fly, and keeping his hands across all stages of production as director, producer, editor, and, in many cases, sound recordist in a career with an output of nearly a doc year, becomes doubly impressive as Wiseman’s confidence with the material matches his trust in the audience to stick with it. That faith in human intelligence and empathy finds a turning point in Wiseman’s career with Welfare (1975). The 167-minute film affords its attentive consideration of America’s broken welfare system the time and space it deserves. Working class people on both sides of the system navigate a process in which the nuances of bureaucracy have real and immediate consequences for people who need help most.

Other corners of Wiseman’s oeuvre prove somewhat more upbeat. Another highlight in TIFF’s retrospective is The Store (1983), which takes audiences inside a Dallas department store during the holiday season. Revisiting a doc like The Store may, on some level, seem trivial while basking in air conditioned theatres for Titicut Follies and Welfare, or the 196 minutes of cool air paired with Domestic Violence (2001), but such a doc also lets audiences experience a time capsule of what now seems like a bygone way of life. As TIFF’s series begins while Hudson’s Bay department stores close across Canada, Wiseman’s look at the Christmas shopping rush proves touchingly nostalgic. Amazon just doesn’t have the some touch, although a Wiseman-esque glimpse at the online behemoth can easily be seen in Union by Brett Story and Stephen Maing—an influence noted in the retrospective with Story introducing Titicut Follies this past weekend.

For me, Wiseman’s best films come in his later act that observes the machinery of artistic institutions. That branch of the Wiseman oeuvre is represented in the Body Politic by Ballet (1995), a hallmark of backstage filmmaking that takes audiences inside the American Ballet Theatre in New York. Ballet may be among Wiseman’s most visually appealing documentaries for its pensive scrutiny of the dancers’ bodies as they rehearse again and again leading up to the big performance. The visual poetry of the dancers in motion gives credit to their artistry and stamina—a refreshing consideration of artistic performance as labour as the ballerinas master the choreography for their patrons’ delight.

The film, which screens in the series on July 23 with an introduction by Hot Docs’ Diana Sanchez, anticipates the latter act of Wiseman’s oeuvre in which the accessible field of arts documentary finds a perfect marriage in the director’s hand for durational cinema. It might not be the most widely praised of Fred’s works, but it’s the gem of the series for anyone who came to love Wiseman through his more recent films like National Gallery and Menus Plaisirs, or even his return to the stage in La danse (2010). It’s proof that, after spending five decades observing institutions, Wiseman became one himself.