Julia

(USA, 93 min.)

Dir. Julie Cohen, Betsy West

Programme: TIFF Docs

Many pounds of butter died for Julia, and their lives were not lost in vain. This scrumptious portrait of Julia Child is a golden study of a woman who whipped up the perfect recipe to rouse Americans from their culinary slumber. As with Child’s heavenly French cooking, the secret ingredient to this doc by RBG directors Betsy West and Julie Cohen is rich buttery goodness. The buttery sheen to Julia is obviously metaphorical, but the doc melts in your mouth while offering bite upon bite of rich, savoury bliss. Julia is comfort food for the soul, and an invigoratingly feminist slice of food-on-film as West and Cohen pay tribute to a woman who not only revolutionized food, but created new space, presence, agency for women in America.

Anyone who worries that they might already know Julia Child’s story after Nora Ephron’s 2009 delicacy Julie & Julia needn’t worry. The drama only tells the highlights of Child’s journey en route to publishing her massively successful and revolutionary cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking. A second helping of Julia Child does the body good. West and Cohen mine an archive of Child’s television success as The French Chef and draw upon the decades in which she entered American homes as an unlikely TV personality and celebrity. With her imposing height, wheezy voice, folksy vernacular, and infectious joie de vivre, she is a delightful presence who inspired audiences to summon the courage to step outside their comfort zones in the kitchen. Child’s larger-than-life personality, moreover, makes the documentary a compelling case for how well Meryl Streep captured the chef in her Oscar-nominated turn in Julie & Julia.

As with the Child portions Julie & Julia, West and Cohen draw upon the chef’s autobiography My Life in France, co-written with Child’s grandnephew Alex Prud’homme. The doc recounts Child’s coming of age in a well-to-do New England family. Stories of bland but serviceable food speak to the English influence on American cooking. Food in the McWilliams household was of the meat and potatoes variety—boiled to expel all the flavours and then laden with fatty gravy—but the insipid nourishment on the plate also embodied the cultural attitude of the time. Food wasn’t talked about and was seen as a domestic affair. Moreover, interviewees in Julia suspect that Child had little exposure to cooking at all. They speculate that the cooking in the McWilliams’ household was done by hired staff with the family sitting down to dine unaware of the work that went into the meals on their plates.

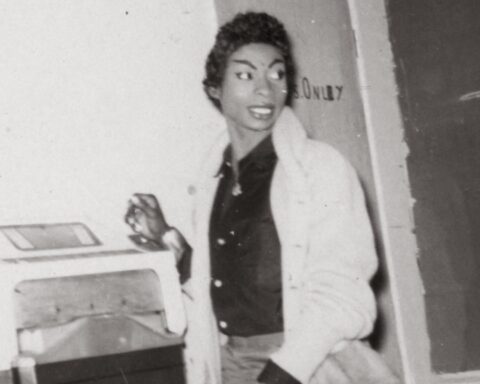

The film sees Julia grow into a rebellious spirit and eventually enlist in the secret service when her other friends were getting married. The serial bridesmaid was not a spy, as urban legend suggests, but a correspondent who handled confidential materials. (Although the influence of her service is humorously apparent during the writing of French Cooking.) The film recounts how Julia met Paul Child during their time in the service, and excerpts from their diaries form a portrait of a relationship that slowly blossomed between the odd couple. Julia credits Paul Child, as do many other accounts, for expanding his wife’s horizons and opening her up to the greater palette of flavours the world had to offer. An assignment in France later and the rest, they say, is history.

Cohen and West delightfully immerse audiences in the sights, sounds, smells, and most importantly, flavours of France during Child’s formative years in Europe. The film delights the senses as it chronicles the day Child lost her culinary virginity to a sole meunière. It’s a tale of love at first bite as Julia conveys how the future chef swooned for the flaky sole prepared in butter, lemon, and salt. Moreover, as Child entered Le Cordon Bleu, the doc gives her credit for asserting her right to participate in male-dominated spaces—doubly impressive considering she shared a class with former infantrymen learning new skills to return to civilian life.

Mouth-watering montages give up-close views of the goods that Child created in her kitchen. As food stylist Susan Spungen, who also prepared the food for Julie & Julia, handcrafts signature Child dishes like bœuf bourgignon, roast chicken, and a poached pear tart dripping with love and goodness, the film uses the Childs’ romance to show how cooking is about far more than feeding our bodies. The Childs’ love story unpacks the social power of food and the intimacy of sharing a meal, particularly the expression of love that goes into a laborious dish. As the film recounts how Julia ran home from Le Cordon Bleu each day to spoil Paul with good food cooked with care, mouth-watering macro photography caresses the ingredients of her delectable dishes. Food porn this exciting should come with an X-rating.

As the film chronicles the publication of Mastering the Art of French Cooking and her explosion on television, it situates Child’s breakthrough at a time when American housewives were encouraged to settle for suburban comforts of convenience and complacency. Canned soup, frozen foods, and jellied “salads” were the norm even though the attitude of the day said that men went out to work and women tended to the home. As Child herself says in the film, if not for cooking, she’d probably have just become an alcoholic if she settled for the life that was expected of her.

Although Child delighted in reaching her husband’s heart through his stomach, Julia gives the chef credit for advancing feminism as much as she did America’s attitude to food. The mere nature of her celebrity, and her mission to give women the tools to empower themselves through food, speaks to this sentiment. The range of footage from her long-running television shows, as well as interviews with her colleagues, speak to how confidently she commanded her role in America’s kitchen. Moreover, as each episode explained how to make a dish, Child’s screen presence also illuminated how audiences—women, but also men—could put themselves forward with the right recipe and the confidence to follow along.

The film also gives Child credit for using her platform as an advocate, as she risked her empire by endorsing Planned Parenthood and supporting LGBTQ rights at a time when people from her era preferred such matters be kept in the cupboard. Life, as with food, is a journey of expanding one’s palette and being open to new experiences. The film shows how Julia understood that sentiment even when she didn’t understand some of the newfangled food phases ushered in by rock star chefs who made her seem anachronistic.

West and Cohen pay tribute to a woman who continues to inspire and nourish audiences and they find in Child a character who illuminates as much about the American psyche, and the fight for progress, as they found in RBG. .Julia is a lovingly crafted buffet of food and feminism that warms the heart. Like Mastering the Art of French Cooking, it should inspire much feasting, cooking, and merriment in the years to come.