“Cinema … serves as an anatomical theatre, an ethnography of bodily phantasms and an archive of somatic uncertainties. — Nicole Brenez

In 1896, Scottish physician John McIntyre produced what is considered the first radiography film. It was composed of three different moving images: a frog’s knee, a human heart, and a stomach. Captured in 1/300th of a second, the film pulses uncertainly, producing an uncanny effect. Made within the first year of the X-ray discovery, this would have been the audience’s first view of new technology—even for doctors. Over time, the scientific film, short and broken up by extensive explanatory notes, has become less of a tool and stands as a novel document that allows us to peer into the realm of the unknown. It almost has the quality of a horror film.

Over history, the strange mysteries of the human body have always been capable of inspiring awe and revulsion. The ordinary beauty of life, as an artistic and spiritual subject, has long been shrouded in paradox. In the Western world, we don’t have to look further than the 2000 years depicting the frail, heavenly, gruesome, adoring, terrifying, and venerated images of Jesus Christ, a man whose body seems graphed with the weight of the entire human condition.

Look at the Isenheim Altarpiece sculpted and painted by, respectively, the Germans Nikolaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald in 1512–16. The centrepiece features one of the most horrific crucifixion scenes in art: Christ’s head hangs limp, his body is a browned-green, and his emaciated form is marked by violence and disease. Quite literally painted larger than life, it must be a towering monstrosity in person, an ode to the frailty of the human condition.

The body and cinema

In Nicole Brenez’s book, On the Figure in General and the Body in Particular (translated by Ted Fendt), she writes about cinema’s capacity to treat the “figure” as part of an extension of a greater trend within art history. Specifically, in her introduction, she treats the question of monstrosity: “Cinema also serves as an anatomical theatre, an ethnography of bodily phantasms and an archive of somatic uncertainties. Ordinary monsters solidify new, symbolic divisions that cinema stamps on the body…But real monsters, resulting from an undertaking of defiguration rather than deformation, endanger and even destroy symbolic circulation.”

The topic of monstrosity as it connects to the human body is tricky. It implies a sense of judgment; something othered, ugly, and unnatural. In 2024, we like to imagine we’ve moved beyond those fears, but in many ways, we’re more detached than ever from the conditions of the human body. Disfiguration, sickness, and death are shrouded in fiction and hidden behind curtains. If we understand monstrosity as a reaction to the unknown, specifically one that represents the fears related to our physical bodies, documentary cinema sheds light on the darkest corners of our mortal conditions.

Let’s begin with a real monster.

Caniba’s monster

In 2017, anthropologist-filmmakers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel released their feature-length interview with Japanese cannibal and murderer, Issei Sagawa. An unexpected public figure in Japan, Sagawa had appeared on Japanese screens before their film Caniba. He starred in some taboo porn films and was interviewed semi-regularly by local and Western media about his crimes and unusual proclivities. The horror of what he did fed into a salacious counter-cultural fame.

Shot almost exclusively in extreme close-ups, Caniba undercuts Sagawa’s public image. The footage is destabilizing. Rather than a surplus of context, an almost complete absence of it contributes to a new perspective on his crimes. Now elderly and in ill health, Sagawa’s laboured breathing, sporadic tremors, and patchy swollen skin overwhelm the viewer. Contrasted with images from his self-illustrated manga, depicting his horrific crimes, the experience is nauseating.

Although Caniba opens with a title card warning that it “does not seek to justify or legitimize” what is shown on screen, it’s difficult not to see the cinematic approach as part of a long legacy in art history that uses ugliness and monstrosity as a reflection of the spiritual quality of its subject. As Pope Innocent III stated, “[w]hen a child is conceived, he contracts the defect of the seed, so that lepers and monsters are born of this corruption…” Disease, deformation and ugliness have long been associated with spiritual unwellness. The film’s treatment of Sagawa’s brother’s self-annihilating perversions further contributes to this spiritual idea of “defective seed.” Caniba represents an extreme example of monstrosity, but one part of a larger legacy within art and thought that ties morality with beauty.

Mental health and monstrosities

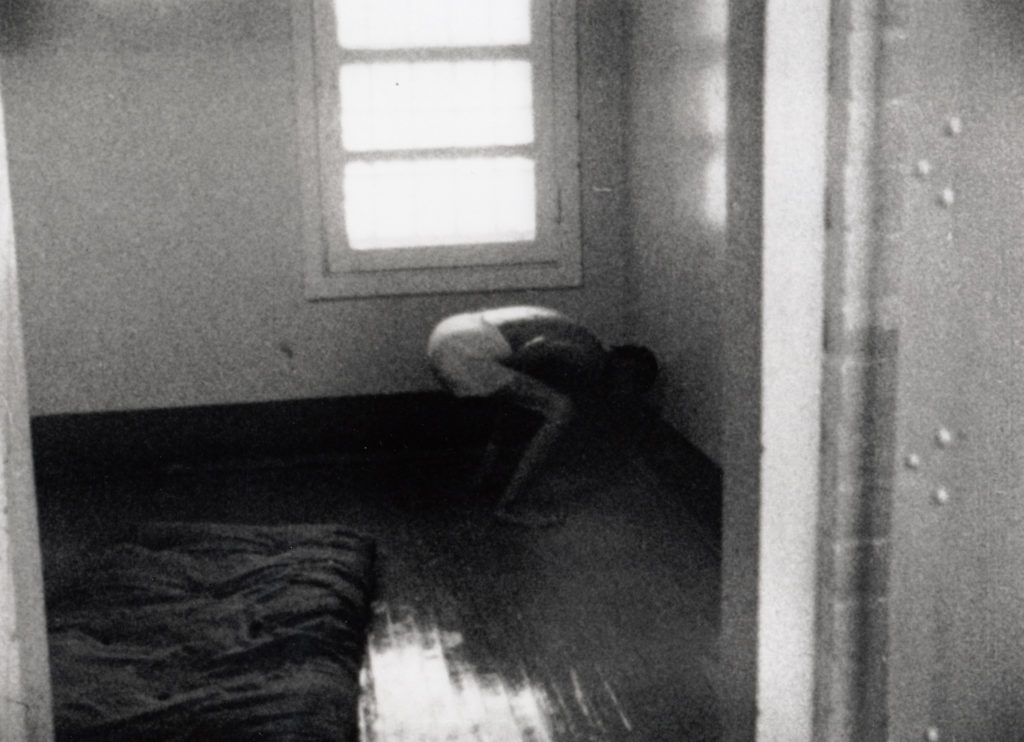

The challenges of depicting the “inner” world of people through outward appearances can be seen in films dealing with issues of mental health. In movies like Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies (1967) and Wang Bing’s ’Til Madness Do Us Part (2013), we can see documentaries that not only treat mental health through an institutional lens but the challenges in depicting people who have often literally been ostracised from society. The subjects’ “deformities” are not always visible to the naked eye, but their myriad of “afflictions” have condemned them to the outskirts.

While varying in approach and context, both films have a similar impact on the audience as they showcase an institutional approach to sickness that seems to have little aspiration toward rehabilitation or dignity. The effect on the audience becomes increasingly claustrophobic. They challenge the audience twofold, asking us to bear witness to what we hide away and also condemning us through form and time to experience that environment through the eyes of the interned. They’re films that challenge our idea that we have somehow transcended outdated moral ideas about goodness and beauty. Why, these films seem to ask, do we hide these people away? They’re not monsters, so why do we treat them as such?

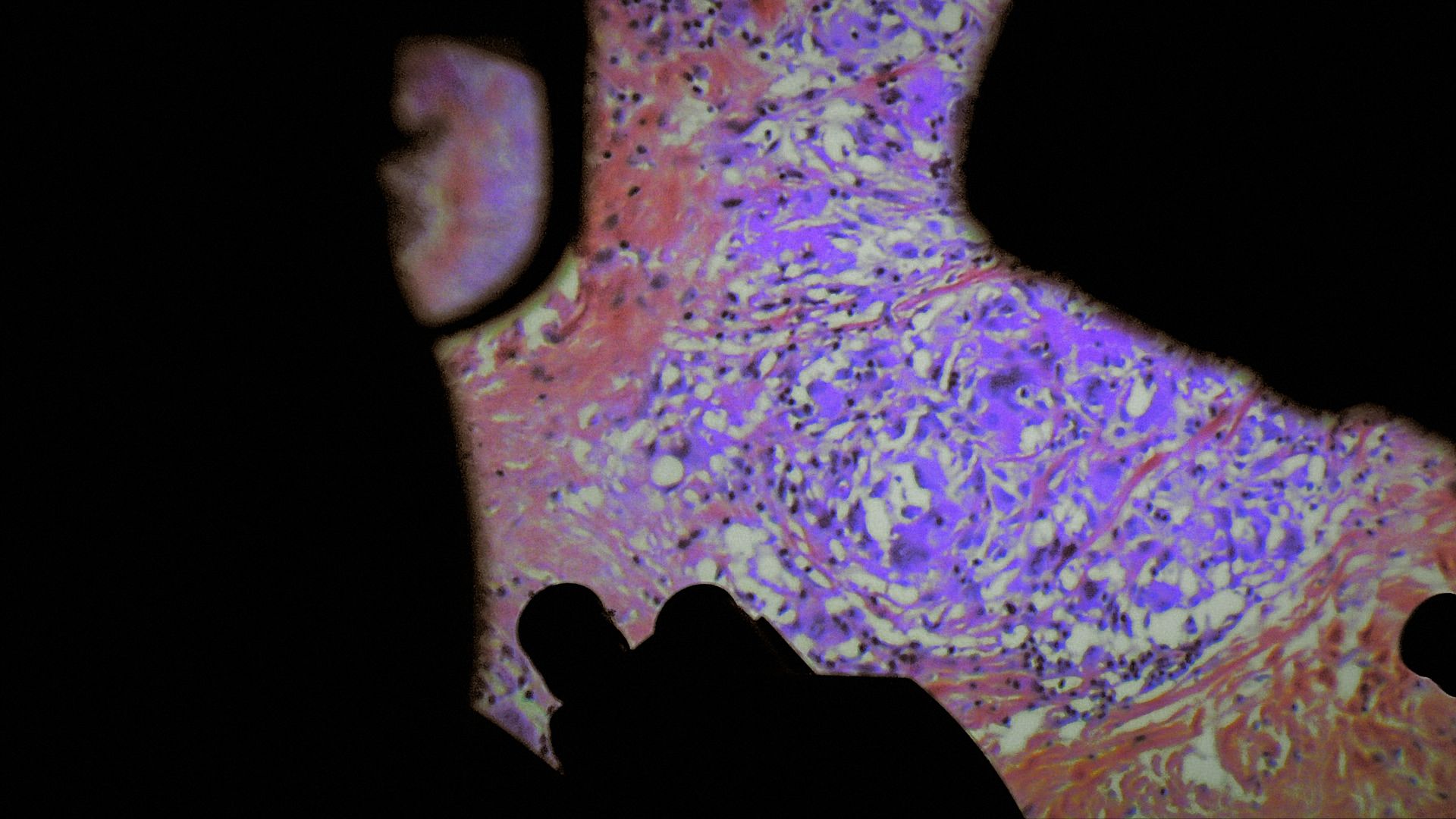

The meaning of hospitals

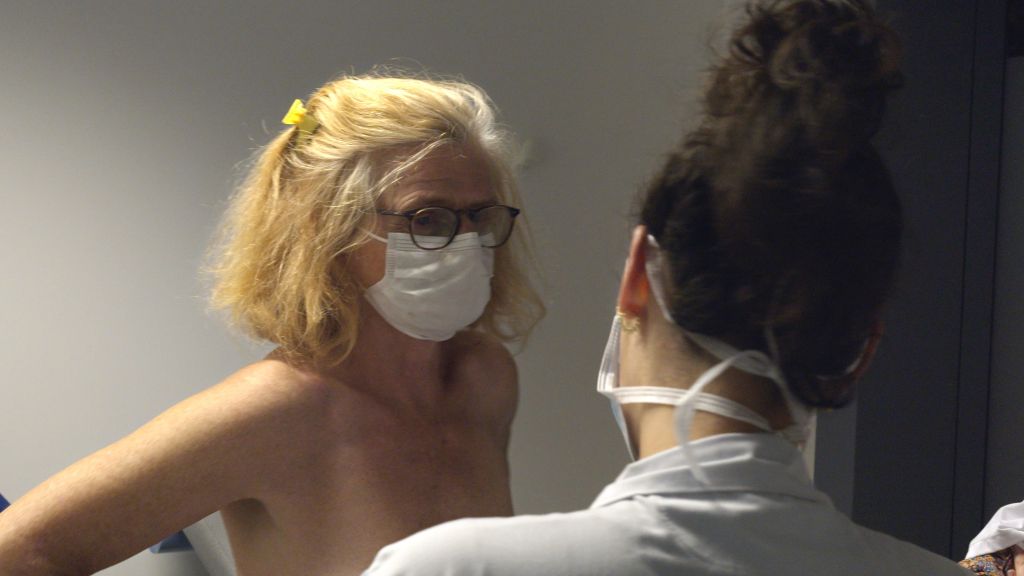

If we return for a moment to the X-ray films of John Macintyre, we can imagine a new approach to the human body divorced from spiritual judgment. Although a relatively niche sub-genre within cinema, many documentarians have entered hospitals and surgeries. In films like Claire Simon’s Our Body (2023) or De Humani Corporis Fabrica (2022) from Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, we are brought physically and psychologically into spaces we similarly cast in shadows. Both films were shot within the French hospital system.

Simon’s approach is not altogether different from Wiseman’s. It’s devised of scenes that build towards a full understanding of a hospital’s function; from examinations, surgeries, protests, and social work, we get a full picture of the labour and life that unfold within a public French hospital.

Exceptionally within her oeuvre, though, at one point in the film, Simon also becomes the subject. As she explains in an early narration, she is terrified of hospitals, and it was part of the impetus to learn more about them. In the process of making the film, she decides to get a checkup, only to discover she has cancer. The personalization of the film hints at a primal fear of sickness and disease. Her documentary sheds light on what is hidden, revealing a world that is not monstrous or horrific, but necessary and occasionally transcendent.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica takes us even deeper into what we look away from. The human body’s monstrosity becomes ordinary, as we’re brought intimately and literally, into the unknown. Most of the film is structured around various surgeries, depicted frankly and simply. Not unlike Simon’s film, the dialogue unveils a deeper institutional world where doctors worry about money and being overworked. The horror of our inner world becomes mundane, almost casual—part of a day’s work.

In the discussion of monstrosity, as it connects with the human body, death becomes the ultimate spectre of horror. Even in the realm of fictional horror, monsters like zombies, vampires, and ghosts embody our fear of death. More often than not, we turn to fiction as a means of escaping the stark reality of that form. The death marks of these monsters—pallid skin, decaying flesh and marks of violence—become palatable when grafted onto the realm of fiction.

In 2025, death suddenly feels more immediate than perhaps any other time in the past one hundred years. We can log on to X (formerly Twitter) and be inundated with images of graphic violence without warning or context. The timeline has become a bomb of surveillance and documentary footage of maimed bodies and brutal murders. The effect can be numbing rather than infuriating. While many documentaries discussed thus far attempt to use art and form as a means of reconnecting the viewer with the conditions of our mortality, online and in this shape, these images render death into “content.”

Stan Brakhage’s monumental The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1971) depicts an autopsy. Shot mostly on a handheld camera, the film departs from much of Brakhage’s other work. It bears witness. There are fewer cuts and more observations. Originally imagined intercut with images of mountain ranges, moons, suns, and clouds, Brakhage completely discarded that idea after seeing the images, “I knew it was impossible (for me now anyway) to interrupt THIS parade of the dead with ANYthing whatsoever, any ‘escape’ a blasphemy, even the ‘escape of Art as I had come to know it—it’s ‘lead’/lied to inner self.”

Death comes for all of us and yet it remains something all of us struggle to face. It has to be covered and concealed, obscured to protect us. Brakhage’s approach forces us to face the ultimate unknown: our bodies after death. His approach becomes sacred in a way that the images on our online timelines never can be. It is attentive and gentle, focused on the contrasting elegance of the mortician’s moving hands and the stillness of the corpse. It pulls back the curtain on the monsters we’ve built in our heads. It dispels the grotesque.

The real monsters

The sacred similarly emerges in The House Is Black (1962), Forugh Farrokhzad’s short poetic documentary on an Iranian leper colony. It’s a film that holds the weight of an ancient world as it depicts a mediaeval disease made worse by lack of touch. It invites us within an outcast community that throughout history was depicted as monsters (just look back to the quote by Pope Innocent III, equating leprosy with monstrosity). The film asks us to look around us, to see the world for what it is. The narration says, “There is no shortage of ugliness in the world. If man closed his eyes to it, there would be even more.” It’s a quote that confronts us with the careless cruelty of our fears as it asks us, “who are the real monsters?