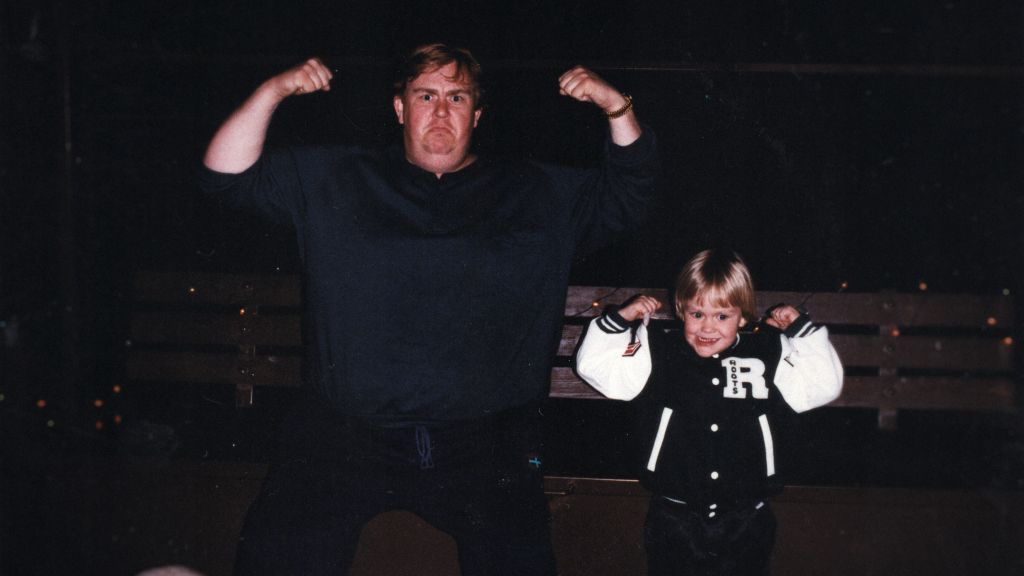

“Ryan called me up and basically said, ‘I don’t want to live in a world where there is not a documentary about John Candy,” Colin Hanks says on how producer Ryan Reynolds pitched him to direct John Candy: I Like Me. “And I said, ‘I think I agree. I don’t want to live in that world, either.’”

Hanks and Reynolds, speaking with media at the Toronto International Film Festival where John Candy: I Like Me served as the opening night gala for the festival’s fiftieth edition, deliver a film that reminds audiences to savour each moment no matter how tough life might seem. (Read our review of John Candy: I Like Me here.) The film, which debuts on Prime Video October 10, takes this question of absence to heart. Interviewees note that Candy was only five years old when his father passed away at age 35. I Like Me sees Candy refuse to take life for granted, knowing his own time would be short-lived. The film builds towards the actor’s 1994 death when he passed at age 43, and his story proves bittersweet three decades later.

The film looks back on Candy’s career from his improv comedy days to SCTV and his performances in films like Splash, Uncle Buck, and Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. “For our family, we were at a place where we were ready to share more, and I think we had a better understanding of what he was going through,” says Chris Candy, John’s son, who serves as co-executive producer on the film. “It very much feels like a swan song and a very beautiful goodbye to our dad. This is the one last great John Candy film that he gets to star in.”

The final credit and long overdue celebration is admirable, but also indicative of Canada’s struggle to celebrate its own talent. The film ends with Candy’s funeral drawing the kind of attention usually reserved for world leaders with the highway closing to facilitate the procession amid an outpouring of love from fans and admirers touched by his work. But the film overall invites a conversation about why Canadians prove reticent to uplift local heroes until they find success in Hollywood or pass away. (John Candy: I Like Me, like last year’s I Am: Céline Dion, is an American production from Amazon Studios.)

“I was saying to Colin earlier that I was sitting at a table twenty-something years ago here in Toronto with Norm McDonald, Bob Saget and Chris Farley,” says Reynolds. “We were at a four-top and we were having lunch and all those guys are gone. And all those guys had their own versions of coping mechanisms and some dangerous, some not. It’s amazing how we canonized the comedian who made us laugh for so many years, posthumously—not so much in the moment, much more posthumously.”

Reynolds says that it took so long for a documentary about John Candy to come partly as a matter of finding the right angle to ensure that the story was more than a eulogy. “It took a long time because with most documentaries, you’re looking for this flip side, and this documentary does have a flip side,” he notes. “It’s just not evil. It’s a flip side about a person that struggled with things that everyone struggles with and filtered that through the prism of joy.”

I Like Me takes an unexpected turn as it explores conversations about mental health. Archival clips show Candy’s experience with anxiety and alcoholism while committing to his work to provide for his children when he’d be gone. Candy’s weight also fuels several conversations in archival interviews. Journalists ask him inappropriately personal questions about his size, star status, and ability to love himself. He responds with grace after shifting in his seat momentarily.

“The bad pitch for the documentary would be when you think of an overweight actor who died too young, you think of guys that unfortunately passed away from a drug overdose, and John didn’t,” says Hanks. “John passed away because he had a bad heart, and there’s a difference there. That launching point then went, ‘If there’s not some nefarious reason that he passed away, what else is there?’ John’s relatability, his everyman qualities, were so detailed and so genuine that he suffered from things that everyone suffers from. That is worth examining and looking at.”

Jennifer Candy, John’s daughter who also serves as co-executive producer on the film, says that she learned so much in retrospect while sharing her father with the world and seeing how he was an early advocate for conversations about mental health. “It was newer or, back then, not talked about as much. I think our dad later in life was just understanding himself and knowing that it was okay to ask for help, be it any way—friends, family, professional help.”

The film weaves through Candy’s filmography as the actor undergoes a push-pull relationship with his weight and heart condition. He avidly works out to keep himself strong, but enjoys legendary nights at the bar, while workaholism carries extra strain that he hides with a smile.

“It’s also the persona that is the shield. The persona’s the maladaptive coping mechanism that keeps you safe. I certainly have my own,” says Reynolds on why the narrative about mental health appealed to him. “The great documentaries are ones where you really learn something about yourself while you’re watching them.”

The actor relates Candy’s story to his own experience as a Canadian trying to make it in Hollywood. “There’s something fascinating about that intersection between somebody who has a predilection for people-pleasing and is also struggling with mental health because a people-pleaser does not ever want to burden another person with themselves,” says Reynolds. “You’re always pulling that back, but mental health doesn’t move forward inexorably or in any way whatsoever without speaking about it, without actually opening it up and saying, ‘Hey, I’m not okay.’ That’s a tricky thing for the people-pleaser because more often than not, you’re going to get, ‘I’m fine.’”

View this post on Instagram

“Nowadays it is such part of the social conversation. It’s very common to hear, ‘I’m taking a mental health day,’ so it interested me that it was not discussed, and yet it was totally okay to be able to mention someone’s weight to their face and make them feel incredibly uncomfortable while they’re trying to give you an interview,” adds Hanks. “It was such an interesting dichotomy to show how much things have changed since John was around. And when you think of John, you think of this great, gregarious, outgoing, entertaining man. But then when you saw him interviewed, he was uncomfortable—very uncomfortable and made even more so by the insensitivity of not only the questions but how they were asked.”

The film uses this discomfort to remind audiences of Candy’s to move fans thanks to his aptitude for juggling comedic timing and dramatic depth. Hanks illustrates this point quite powerfully as the film reaches its climax with a scene of Candy’s best work: his monologue in Planes, Trains and Automobiles. As Del Griffith, the hapless salesman who irks Steven Martin’s uptight traveller Neal Page, Candy drops his character’s armour after Neal berates Del for being impossibly happy. Martin recalls in the documentary that watching Candy’s reaction in the scene was as if he was ripping the actor’s own heart open.

“I could be a cold-hearted cynic like you, but I don’t like to hurt people’s feelings,” Del reponds. “I like me. My wife likes me. My customers like me. ‘Cause I’m the real article. What you see is what you get.”

The vulnerability and ability to articulate self-love and self-worth affords John Candy’s story its well-earned catharsis. Reynolds says it was important to make audiences laugh in the end to remind them of Candy’s power. “There’s a temptation to paint the sad clown character,” he says. “John to me represents togetherness, joy, and not punching down.”

In a way, that all comes back to the national character that Reynolds says makes John so accessible, relatable, and against the grain for Hollywood star power. “John is the spirit of Canada. You don’t have to look for that,” says Reynolds. “Listen to the movie and the movie will speak to you. Sometimes it’ll yell, especially if you’re prepared. If you’re prepared, you’ll really hear it. John’s all over it. I think John is the spirit of Canada.”