The Eurovision Grand Prize for Documentary from the 1960 Cannes Film and Television Festival is a large silver medal housed in a velvet-and-satin-lined box. The prize was awarded to The Back-breaking Leaf, a landmark in direct cinema. It’s a documentary that continues to be shown around the world, a movie that may be the crowning achievement of the seminal Candid Eye series at the National Film Board of Canada.

Fifty years on, the box is broken, the satin torn, the medal coming loose from its moorings. Its caretaker—the prize’s recipient, Terence Macartney-Filgate—framed the wrecked award, along with the letter that accompanied it when the putative owner of the prize, The National Film Board of Canada (NFB), sent it to him in this condition in 1982. In part the letter reads: “We regret the poor condition of the prize. Damage may have been sustained in shipment or in storage. We hope that with your personal care the award could be restored to its former beauty.”

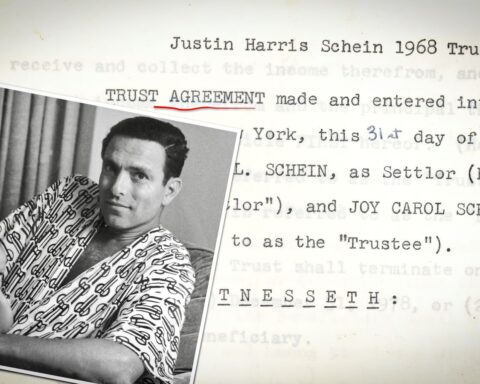

Now in his mid-eighties, but looking decades younger, the man known to everyone as Terry Filgate is modest to a fault. Like many of his Canadian colleagues and collaborators, this is probably the reason that his considerable accomplishments are not better known. The American and British filmmakers he worked with have virtually all had their share of the limelight. The Canadians who helped start it all have somehow been left behind.

But it was undeniably a small group of Canadians at the NFB in the late 1950s who helped shape and even invent documentary film as we know it today. Filgate is a key figure in that group.

Terence Macartney-Filgate was born in the United Kingdom in 1924 and grew up in colonial India, where his father was stationed. When he turned 18 in 1942, he immediately joined the Royal Air Force and was sent to Canada to train under the Commonwealth Air Training Plan. He flew 17 missions as flight sergeant on B-24 Liberators over Italy during the Second World War. After the war, he attended Oxford and earned a master’s degree in politics, philosophy and economics.

After graduating, Filgate returned to Canada. At the outset of the Korean War, he joined the RCAF reserves and as a result was recruited by the NFB in 1956 to write instructional films on subjects ranging from ground handling of aircraft to crash rescues to personal hygiene.

“They were a useful beginning,” Filgate recalls. “You learned the grammar of film.” When the NFB initiated its Candid Eye series in 1958, Filgate jumped at the chance to participate. Along with Roman Kroitor, Wolf Koenig, Stanley Jackson and William Greaves, and under the leadership of Tom Daly, Filgate joined a programme that would change the course of documentary filmmaking.

“We had seen British Free Cinema, Momma Don’t Allow [Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, 1955] and others. That was the kind of approach, the sort of subject we wanted to shoot,” says Filgate.

In addition to British Free Cinema, another of the key figures in the Candid Eye series, director Wolf Koenig, cites the influence of the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson, as well as earlier giants of documentary filmmaking like Pare Lorentz (The River, The Plows That Broke the Plains).

Together, these predecessors inspired Koenig, Kroitor and Filgate to try a new approach to documentary. They were to make 14 films in the series, which was aired on the CBC.

The Candid Eye was justly hailed as the series of films that defined direct cinema, or cinema-verité documentary—it certainly had predecessors, but no series of films did more to establish the look and feel of modern documentary film. Still, Filgate demurs when asked if the Candid Eye filmmakers believed they were making a new kind of film. “We didn’t think we were doing anything special,” he says. “They were just stories we wanted to tell. And this was the way to tell them.”

But to tell the stories they wanted to in the way that they envisioned, Filgate and his colleagues needed cameramen who would take risks shooting in unorthodox, even radical, ways.

“Most of the cameramen at the Film Board couldn’t understand what we were doing. They wanted three lights just to shoot a close-up of s someone picking up a telephone,” Filgate recalls.

Koenig was already a skilled cameraman.In the early 1950s he shot several shorts for Colin Low, as well as Norman McLaren’s Oscar winner, Neighbours. On the French side of the NFB, there was a group of eager and brilliant young cameramen who were willing to join their English counterparts in trying something new. Michel Brault, Gilles Gascon and Georges Dufaux joined the Candid Eye group. Despite the language divide, the young Francophones loved working with the Anglophone group and recognized the significance of what they were doing. Michel Brault recalls: “I remember being very glad to be assigned to Terry since he was pushing me to take risks, and that attitude set the pace for all the films I did after that.” Together they helped pioneer techniques like the hand-held camera and flashing (pre-exposing the film to increase its sensitivity to light—a technique critical for natural-light shooting).

And over the Christmas season of 1957, the team set out to make a film called The Days Before Christmas.

Seen today, the film retains its power. Directed by Filgate, Koenig and Jackson and photographed by Koenig, Brault and Dufaux, it is a loose tale about Christmas activity, from shopping to choir practice to phoning Christmas greetings overseas. The most famous moment in the film is Koenig’s brilliantly unexpected following shot of a Brink’s guard’s gun as he carries the day’s money to his truck. The Days Before Christmas has no narration and no conventional story. It is held together more than anything else by its aesthetic. It is concerned with capturing life as it was experienced. At times, the film verges on the abstract.

The Days Before Christmas was probably the first film anywhere to use handheld 16mm shooting as an aesthetic tool to capture the real world. The Candid Eye filmmakers rejected the label “cinema verité” as pretentious and instead chose to call it “direct cinema.” In any case, The Days Before Christmas was a revolutionary step.

Filgate says it was Koenig who he remembers first shooting handheld. “I’d never shot anything before. I had only ever shot stills,” he says. “But Wolf encouraged me to shoot. So I never shot on a tripod. I always shot handheld. It was only later that I put the camera on a tripod—I learned backwards.”

In the first year of the Candid Eye series, Filgate directed four documentaries that would begin to define a movement in filmmaking that continues to this day: Police; Blood and Fire (Best Documentary at the Canadian Film Awards, the predecessor to the Genies); Pilgrimage; and The Days Before Christmas. All four reflect an observational, non-judgmental style that had rarely been seen before in documentaries.

With the lightweight Arriflex-S camera, Filgate was also one of the cameramen on Police and Pilgrimage. Of these early experiences he says: “I’d written so many documentary scripts, and they were shot like features. They were planned. The idea with the handheld camera was to free oneself, to go where the scene went. But you had to have a kind of a sixth sense about what would be useful, what was working.”

In 1959, Filgate directed and shot the now legendary film The Back-breaking Leaf. This revolutionary film would influence generations of filmmakers. Shot on a tobacco farm in southern Ontario, the half-hour documentary chronicles the lives of transient tobacco pickers and farmers. The Candid Eye series had been an aesthetic experiment: films about situations and events. In The Back-breaking Leaf, Filgate added his own personal concern: people.

“They weren’t particularly interested in people at the Candid Eye. No one had made a movie about migrant workers before. I thought they would make a good subject.” What is striking about the film even today is the feeling that the filmmakers are genuinely interested in their subjects. The Back-breaking Leaf gives voice to the tobacco workers (for the first time in the series, Filgate can be heard asking brief impromptu questions of the workers). But the film is not unsympathetic to the difficulties of the farmers. Like the other films in the Candid Eye series, The Back-breaking Leaf is shot extemporaneously, but precisely—the shots are beautiful to look at. The penultimate shot—tracking with a picker, his bronzed back bent as he walks the length of a tobacco row—is a brilliant shorthand of Filgate’s aesthetic and his social concern.

Like the emergence of realist novels, this film helped mark the beginning of a movement in documentary filmmaking: unscripted films about real life, in real situations, with real people. The Back-breaking Leaf went on to win many awards: at Cannes (the Eurovision Grand Prize), the Antwerp Film Festival and The New York Film Festival.

By 1960, Filgate had become the single most important influence on the development of direct cinema in the Candid Eye series at the NFB. Of the 14 films produced in the now-famous series, Filgate directed or co-directed seven and was cameraman on two others.

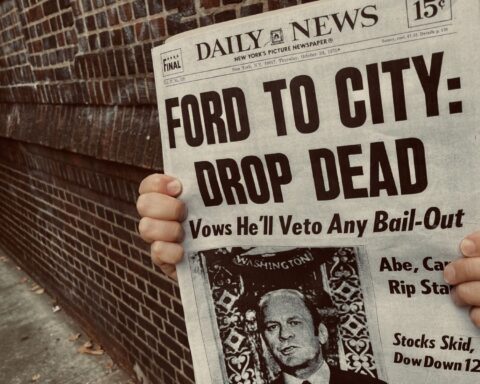

In 1960, Filgate took a leave of absence from the Board to work in New York. That year, he was a cameraman and sequence editor on Primary, a film about the Wisconsin Democratic presidential primary between Hubert Humphrey and the eventual winner and legendary president John F. Kennedy. Primary is often cited as the first fully realized example of direct cinema in the United States and is perhaps the most famous example of it. It is correctly praised as an influential document. And most of those who were directly associated with it—Robert Drew, Al Maysles, D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock—are justifiably admired for their work.

But what is often overlooked in appraisals of the film are its antecedents. Robert Drew has frequently claimed in interviews that they were creating something entirely new. It is undeniable that they were doing important work. But while Primary takes on a political subject, its aesthetic, method and technique are virtually identical to that of the Candid Eye films.

In fact, Terry Filgate’s influence on the film is hard to deny. Techniques that he and others had developed at the Film Board—the observational camera, the personal approach to the subject, handheld tracking shots that put the viewer in the middle of the action–-are what make the film a lasting and influential document. Albert Maysles’ famous shot following John F. Kennedy, which allows the viewer to observe him without interruption, is stunning. But it echoes the shot of the Brink’s guard’s gun in Days Before Christmas, and the shot of the tobacco picker’s bronzed, bent spine in The Back-breaking Leaf. More important than any single shot is the idea of following the subject without intervention. In this case it was Kennedy and Humphrey. The filmmakers simply recorded their day-to-day activities. And that was precisely the idea behind the Candid Eye series.

Filgate’s sixth sense of what to shoot also gave insight into what not to shoot. He recalls filming Humphrey on the night of the returns. Filgate and Al Maysles were with the Humphrey camp along with the rest of the media. As the returns came in the mood was glum. Filgate knew what was coming. Maysles wanted to film, but Filgate told him to put his camera under a nearby table. “I knew they were about to throw the media out of the room. I said we ought to help make sandwiches. When the time came, Humphrey’s sister Fran told him that we were helping and he should let us stay.” As the returns continued to come in a hollow joviality takes over the room. “When is Red Skelton on?” Humphrey wonders. “We like him, he’s our favourite.” Filgate and Maysles were the only ones left to capture it. Without the abiding interest in people, and the ‘sixth sense’ for where the scene was going, these revealing scenes would never have been shot.

Without a doubt, each of the other cameramen on Primary —Albert Maysles, Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker—brought their own considerable experience to bear. But the connection between one of Primary’s cameramen, Terry Filgate, and the Candid Eye series, is almost never mentioned.

Still, some of the filmmakers were aware of the work being done at the Film Board. Pennebaker, along with Al Maysles, had been shooting handheld for some time, with mixed success: “When I saw Terry and his handheld Arri I felt a sudden professional warmth for a like-minded filmmaker,” says Pennerbacker now. ”In my mind, Terry was the first I had encountered that was dealing with the camera the way we were trying to … Terry was very helpful in our beginnings, with Drew and especially with Al Maysles and myself, in learning the tricky ways of the handheld camera… He was one of the first filmmakers to whom we paid attention and his films, especially The Back-breaking Leaf and The Days Before Christmas, were a big influence.” To which Filgate responds: “Penny is very generous.”

But while Primary retains its immediacy and its sense of being in the moment, it doesn’t overtake the films of The Candid Eye. The camera work in Primary sometimes seems tentative and immature. And it rarely equals the beauty and precision of the best of the Film Board’s series. It undoubtedly has a place in the evolution of documentary, but without its famous political subject it almost certainly would not have overshadowed its predecessors.

In 1963, Filgate was hired to shoot a film about the poet Robert Frost for producer Robert Hughes. Shortly after shooting began, the director, Shirley Clarke, was forced to leave the project and he took over directing the production. “There were scenes with Frost lecturing—just a shot at the podium, no cutaways at all. We had to reassemble the audience and play them a recording of the lecture to shoot their reaction.” Filgate shot extensively on the project, but it was a departure for him: it was filmed in 35mm with a tripod-mounted Mitchell BNC (sometimes two at a time). “It was absurd,” he says. After the film emerged from the cutting room however, Clarke claimed contractual rights to sole credit. Filgate’s credit was reduced to: “Fall sequence co-directed by Terence McCartney [sic]-Filgate.” The film, Robert Frost: A Lover’s Quarrel with the World, went on to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

The late 1960s saw Filgate return to the NFB, directing a number of social documentaries, including the Lewis Mumford on the City series. Before departing the Board again, he directed Up Against the System, a film about welfare recipients, which was one of the finest documentaries made for the influential Challenge for Change series under executive producer George Stoney.

At the end of the 1960s, Filgate worked with his erstwhile Film Board colleague, director William Greaves, and shot (as well as appeared in) the cult hit Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One. Greaves’ willingness to accept the shifting winds of his production, his rebellious film crew and their decision to record themselves was brave, and groundbreaking. That’s why it is a landmark film. At the same time Filgate’s characteristic handheld camera work is what makes this film absorbing: his extemporaneous experimental camera defines the movie and helps it cross the border between drama and documentary. Again, it is the ideas developed in the Candid Eye series that make the film possible. Without that aesthetic, one on which Greaves and Filgate had collaborated time and again, a powerful idea for a film would have been lost. The film has been cited as the beginning of self-reflexive cinema. American director Steven Soderbergh is a longtime fan: “I just thought it was one of the most amazing things I’d ever seen. I couldn’t believe how great it was, and that it wasn’t famous.”

Over the years, Filgate worked on many award-winning films. In 1964, he directed the searing documentary Changing the World: South African Essay. It won a Peabody Award. He worked as cameraman with animator Gerald Potterton and Harold Pinter to make the quirky and funny Emmy Award–winning Pinter People for NBC. He directed the classic look at the history of black people in Canada, Fields of Endless Day. In 1978 his film The Hottest Show on Earth, directed with Derek Lamb and Wolf Koenig (its improbable and very funny subject is home insulation), won Best Documentary at the Canadian Film Awards. Filgate directed Dieppe 1942, which was nominated for seven Genie awards, including Best Director and Best Documentary. He shot and directed the documentary Timothy Findley: Anatomy of a Writer, joining forces with his longtime collaborator Don Haig. The film won the Donald Brittain Award for Best Social/Political Documentary at the 1993 Gemini Awards.

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s Filgate often worked at the CBC, including several years with Adrienne Clarkson Presents. He also spent several years teaching film production at York University, where he influenced countless students, among them cinematographer Mark Irwin (There’s Something About Mary, Oscar winner Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got, The Fly). In a 2009 interview in American Cinematographer magazine, Irwin cited Filgate as his key early influence: “Terrence McCartney[sic]-Filgate was an early pioneer of direct cinema and taught the Maysles brothers and D.A. Pennebaker the vérité style a generation before he taught me.”

In 1994, he went back to work for the NFB, where he directed Canada Remembers, a three-hour special about the Second World War commissioned for the 50th Anniversary of D-Day. Some saw Canada Remembers as a departure for Filgate. The interviews were shot on a tripod against a black background, and were intercut with footage from the Second World War. But his focus was the same as ever: the people. When an interview yielded an honest and true story he would press on. More than 100 hours of interviews with veterans yielded a film that was seen by over two million viewers.

Filgate continues to be on the cutting edge of filmmaking. In 2003, he completed shooting a sequel to Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One in New York using the newest digital-video technology. The film was executive produced by Steven Soderbergh and actor Steve Buscemi. During the course of filming, Filgate spent time teaching Buscemi how to shoot. In 2006, at age 82, he completed Raising Valhalla, a documentary on the construction of the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts.

Every fan of documentary should know Filgate’s biography. (If she learned you were from Toronto, the great film critic Pauline Kael would automatically ask if you knew Filgate: “He’s an amazing guy, his films are incredible,” she said.) Perhaps it is a particularly Canadian affliction that lets us forget our own giants of documentary film. While the Americans burnish their own reputation—and good for them—we let our filmmakers’ awards disintegrate, while their reputations tarnish. And we leave it to them to “restore them to their former beauty.” Surely it is our responsibility to do just that.

But Terence Macartney-Filgate dismisses any suggestion that he set out to do something important. He simply did what interested him. “I still enjoy shooting,” he says now, “focusing on something—a shot that the viewer thinks is easy and natural, but is really hard to get.”