The Longest Goodbye director Ido Mizrahy says his documentary original planned to tackle a mission to Mars, but that he ultimately found the core of the story here on Earth. The film, which premieres as the Day One selection in the Sundance Film Festival’s World Cinema Documentary Competition, offers a case study in letting the story be a filmmaker’s guide. The Longest Goodbye considers the personal, emotional, and psychological toll that astronauts face amid space exploration.

“My aim is rarely topical, thematic, or science-based,” says Mizrahy, whose credits as a director include the award-winning matador doc Gored and the character-driven true crime study Patrolman P. “I find it hard to think of a story as a big canvas, like the mission to Mars. It was great to meet the engineers, flight directors, and astronauts, but I kept thinking, what’s my story?”

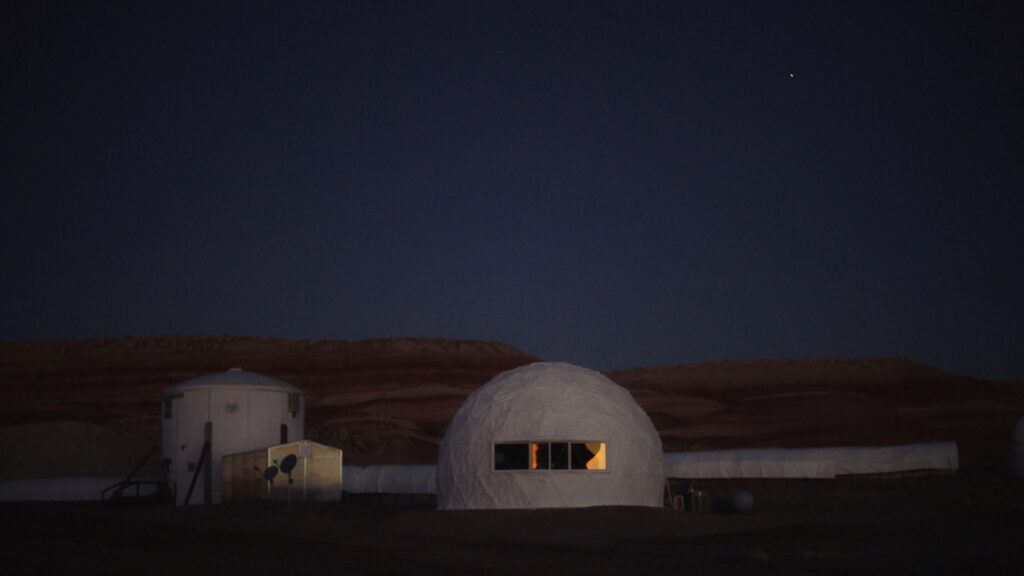

Mizrahy says that the turning point for the story came when he met Dr. Al Holland. The NASA psychologist studies the prolonged effects of isolation on astronauts. The Longest Goodbye finds a grounded story in isolation on Earth—something to which we can all relate—when it introduces Dr. Holland and NASA’s HERA program. The human research series simulates space missions with recruits on Earth. Researchers observe their behaviour in order to assess the impact of factors like isolation and confinement.

“That meeting turned the whole thing upside down,” notes Mizrahy. “Here’s a beautiful metaphor for what we go through all the time, but it’s real. This job is real and if he doesn’t do it well, these missions are going to be incredibly dangerous. It was a nice meeting place between finding something to document and a way to talk about something that’s much more terrestrial.”

Catching the Stars

Mizrahy says that accessing NASA materials, especially pertaining to ongoing studies, poses some challenges. Among them is NASA’s prerequisite that filmmakers have a North American distributor before accessing locations and experts. (The caveat simply reflects the practical matter of vetting the thousands of access requests that NASA receives annually.) Mizrahy notes that once PBS came aboard The Longest Goodbye, things opened up.

“Once that first door opens and you realize there are a lot of other doors,” reflects Mizrahy. “NASA headquarters approved the project then moved us over to Johnson Space Center, which is where the astronauts and the human part of the mission are. That’s where there are many other doors. Getting to the astronauts is really complicated.”

The Longest Goodbye weaves between the stories of former astronauts, like Cady Coleman, and current ones like Kayla Barron for firsthand accounts of the emotional weight of journeying to space. At the same time, talking heads like Dr. Holland and former HERA participants unpack universal elements psychology that NASA considers. Barron offers perspectives about current research as part of the ARTEMIS 1 mission, which probes deep space exploration to learn the capacity for human existence on the Moon with an eye towards extending the mission to Mars. Meanwhile, Coleman reflects upon her career, which included an extended mission to the International Space Station that clocked 155 days in space.

“Once one of the astronauts is on board, then everything looks different because they are the stars of this whole story. They’re the brand,” notes Mizrahy.

The Coleman Family Archives

The director admits that Coleman was initially skeptical about participating even though her story ultimately gives The Longest Goodbye its strongest emotional beats. “We were introduced by someone she had worked with at NASA. I was this filmmaker asking zero questions about science and exploration,” laughs Mizrahy. “Everything I wanted to know was about her family, what it was like to mother from space, and maybe some uncomfortable things about her relationship with the psychologists at NASA.”

Through Coleman’s story, The Longest Goodbye observes what it means to juggle two lives: one on space and one on Earth. The film enjoys extraordinary access to video communications between Coleman and her husband Josh and son Jamey. Videos from their 2010-11 pre-Zoom conferences offer moments of shared joy, heartache, and frustration. Jamey, then a child, particularly struggles with detachment. Like his mother, though, he appears in The Longest Goodbye to share the overlooked human costs of space travel.

“I think Cady saw this as an opportunity to have her family and her son talk about some of these things that weren’t a hundred percent resolved,” says Mizrahi. “She showed me all 45 or 50 hours of their video conferences—every conversation they had from space.”

In probing such intimate psychology within individuals who achieve a feat as rare as space travel, Mizrahy thinks The Longest Goodbye opens up a fresher, more humanizing portrait of astronauts. “The contemporary astronaut is a different type. [NASA] wants people to be much more open, much less perfect. There’s something much more durable about that as opposed to what we think of as The Right Stuff or the ’60s and ’70s kind of hardened astronauts who do sprint-like missions where they just have to survive and get back,” observes Mizrahy.

An Unlikely Quarantine Fable

The study of isolation, moreover, makes The Longest Goodbye a stirring unintentional allegory for life during the COVID years. The film’s Canadian producer, Paul Cadieux (Gaza, Advocate), says the project began long before lockdowns. He recalls meeting Mizrahy and producer Nir Sa’ar at Co-Pro in Tel Aviv in 2019. (The Longest Goodbye is an Israeli-Canadian co-production.) The COVID parallels obviously aren’t intentional, but the filmmakers acknowledge the echoes between the astronauts’ stories and work habits and their own lives amid quarantine.

“My role is to accompany the creators and make sure they have the tools to tell the story,” says Cadieux. “You have to think outside the box. Prior to the pandemic, filmmakers were not thinking if they could do interviews from a distance or finding different crews to hire locally rather than sending them from their home base. I’ve been arguing with filmmakers for years that you don’t have to be sitting in the editing room for the film to make sense and to follow your edit.”

Although Mizrahy was able to come to Montreal for mixing and colour correction, Cadieux says he worked on post-production with filmmakers remotely with relative ease during the pandemic. In some ways, the production model reflects the good science favoured by the astronauts. “I think especially in documentary, the pandemic period helped to find new ways to do things more flexibly than throwing people on planes,” adds Cadieux. “As we become more conscious of the carbon imprint of sending crews halfway around the world, we become more conscious of how we might be able to do things as efficiently without shipping cameras halfway around the world too.”

A Grounded Space Story

Mizrahi agrees that adapting production and working remotely happened with relative ease. However, the director relates to the changes that arose in telling the story: the emotional arc and deeper philosophical questions raised by the stories of the astronauts and HERA participants. “At the beginning of the pandemic, I was really anxious about being isolated and not being able to spend physical face-to-face time with my social support network,” says Mizrahi. “What I found was that, as we were getting closer to these lockdowns ending, I suddenly wasn’t eager to leave my house. I felt that comfort of isolation. There’s something in the story too about the fear of coming back.”

As Sundance blasts off with The Longest Goodbye and marks a two-year return to the in-person festival, the film leaves audiences with complex questions with which they’ve collectively wrestled over the last two years. “If the psychologists and the astronauts are constantly thinking about how they stay connected and continue their lives in their terrestrial base, suddenly you can realize, ‘I don’t want to come back.’ Maybe it’s easier to leave or uproot,” says Mizrahi. “Maybe ‘home’ could be something different.”