Sly Lives! (Aka the Burden of Black Genius)

(USA, 112 min.)

Dir. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson

At the beginning of Sly Lives!, director Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson asks his interviewees variations of the same question: Is there such thing as Black genius? The responses reflect a mix of self-reflection that the interviewer and interviewees recognize. There’s an awkward pause, some cautious laughter, and maybe a long blink. But then the respondents confidently look into the camera and say they love it when they see it. Why genius for some artists needs a qualifier remains an unanswered question in Questlove’s sophomore feature, but the collective assessment of the career and legacy of musician Sly Stone (né Sylvester Stewart) proves the merits in recognizing Black genius—or Black excellence—when credit is due.

This engaging follow-up to Thompson’s Oscar winning feature debut Summer of Soul (Or…When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) proves that the music producer isn’t a one-trick pony when it comes to making quality docs with parenthetical titles. Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) follows a similar approach to Summer of Soul as Questlove cranks the nostalgia factor to the max. A sumptuous blend of archive and a who’s who of talking heads combine to create a notable assessment in musical history. It’s a great deep dive into a musician’s signature sound, persona, and influence.

Sly Lives! begins its joyously exclamatory look at Sly and the Family Stone by situating the music as it emerged from a place in time. Interviewees place Sly Stone in the 1960s when the civil rights movement had the USA facing a reckoning. But as a young man who grew up in a mixed neighbourhood, Stone tells in archival interviewees that he didn’t differentiate his Black friends from his white ones. His dad, meanwhile, said he’d step on a ship if it meant sinking all the white folks in America. Stone, recognizing a generational difference in perspective, tells how he corrected his dad and, in turn, the nation, by using music to usher change.

A chorus of talking heads, including Family Stone members Cynthia Robinson and Jerry Martini and musicians like André 3000, Chaka Khan, Nile Rodgers, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, George Clinton, and Vernon Reid credit the group for breaking barriers in a divided America. When airwaves offered barbershop quartets, crooners, boy bands, and doo-wop girl groups, having a multiracial band that crossed genders was an anomaly. However, the interviewees in Sly Lives! echo the talking point of many music documentaries in crediting music for leading the change in terms of race relations in America.

A breakthrough came when Stone worked with The Great Society for their track “Someone to Love” and proved his ingenuity as a producer. Band members recall how he made the song click by listening to their first attempts and then tweaking every instrument and player on the song. Stone’s legacy as a producer weaves throughout the film. But there are also stories about how his ability to give each instrument, voice, and element of a song its own hook inspired generations of artists to sample elements of his music. The funky beats of Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation,” for example, continue to inspire audiences to groove thanks to six seconds lifted from Sly and the Family Stone’s “Thank You.”

Sly Lives! isn’t afraid to dig into the sounds that helped define this era of music. Bassist Larry Graham, for example, outlines his technique of “thumbin’ and pluckin’” that he developed when playing without a drummer. He makes the bass slap to keep the rhythm, and when combined with a drummer with the Family Stone, the extra flavour adds to the funk. It helps, too, that Thompson obviously loves nerding out on the music front. The producer becomes an infrequent onscreen presence as participants take a hands-on approach to the discussion of musicality. They engage with the sound boards and explore drum machines, illustrating Stone’s ability to imagine new sounds with limited tools.

The film inevitably lapses into the rise-and-fall narrative to which celebrity docs are destined. However, Thompson frames it within the question of Black genius. He underscores how Stone’s struggle to hold strong under pressure—his career basically petered out with drug use—was foreseeable. The film asks why Black artists have to work much harder than their white contemporaries when seeking common goals. It’s a pressing question for Stone’s career when many white artists benefited from his work and directly lifted his style and songs.

Stone, who is still alive, doesn’t appear among the contemporary interviews. After interviewing Stone for Summer of Soul!, Thompson reportedly recognized the artist’s declining motor skills and opted not to put him before the camera. It’s a fair creative choice that leaves a hole in the film on one hand. On the other hand, Sly Lives! finds key archival interviews that further the conversation. He took on the question of being a trailblazer and the weight that carries decades ago. He’s been answering such questions his entire adult life.

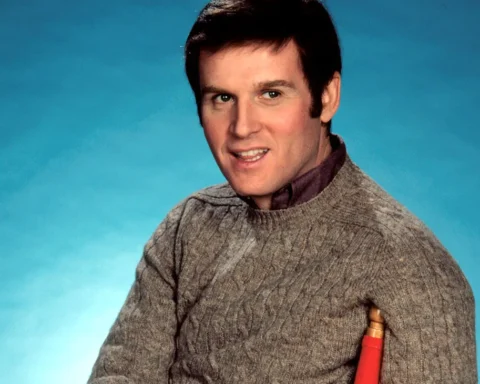

Past interviews see Stone anticipating the conversation his peers have in the film, while perhaps the most telling piece comes in his appearance with Dick Cavett. The late night host continually bates Stone for an altercation. Stone, high as a kite, doesn’t bite. He tells Cavett that he the band would embrace a square white guy in a suit if he wanted to play. But these overt microaggressions illustrate the racial dynamics that complicate Black genius. He has to prove his worth twofold.

The question of Black genius, moreover, hangs throughout the film. Thompson clearly recognizes the expectations he set for himself after Summer of Soul!. Feature debuts are rarely as strong as that one. Perhaps inevitably, he follows a similar pattern of archive and intimate conversational interviews. It’s a model that works, but one that invites comparison. With Summer of Soul!, he unearthed something new with the rarely seen footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. That footage included some great images of Sly and the Family Stone, which don’t appear here, although Sly Lives! boasts lots of concert scenes from the earliest known footage of the band to a coked-out jam at Woodstock. What’s new here is the perspective as artists re-examine the rise and fall narrative through the lens of double standards.

Lightning doesn’t strike twice, but Thompson confidently proves that he’s as confident in the director’s seat as he is in the recording studio. Perhaps the film does answer the question of Black genius by the end, if only indirectly.