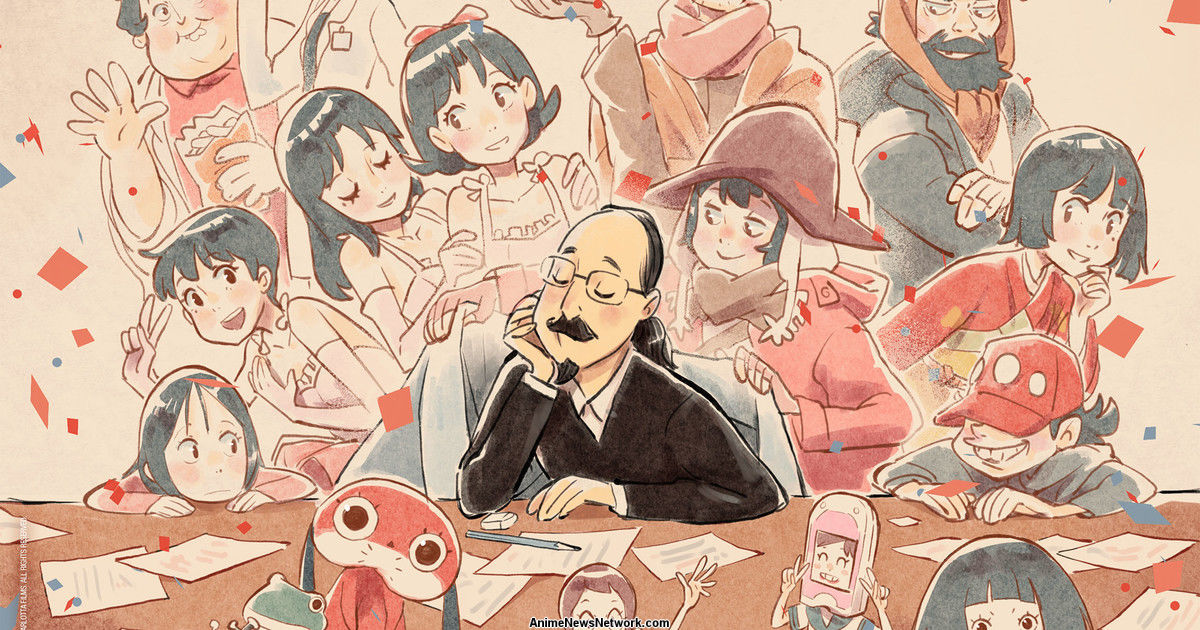

Filmmaker Satoshi Kon’s brief career consisted of only a small collection of works – 4 features, 1 series and several Mangas – but his impact was great. Like an unexpected lightening bolt, his films were a creative shock to the system that forced many to reassess what Japanese animation could achieve. As director Mamoru Hosoda (Wolf Children) notes at the beginning of Pascal-Alex Vincent’s documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, Kon “created animated films that were as powerful as live-action films.” Though pancreatic cancer blew out the candle of his life at the young age of 46 in 2010, his legacy still burns bright in the artists he continues to inspire.

Pulling together animators, animation historians, voice actors, producers, and directors – including Darren Aronofsky , Jérémy Clapin (_I Lost My Body), Marco Caro (Delicatessen), Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell), and Rodney Rothman (Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse) to name a few – Vincent’s film charts a chronological path through Kon’s stunning career. Skipping over the director’s youth, aside from mentioning Kon had dreamed of becoming a “mangaka” (comic artist) at a young age, the documentary kicks into gear by explaining that Kon was heavily influenced by Katsuhiro Ôtomo, whose numerous works included Akira.

Initially patterning his expressive drawing style after Ôtomo’s, Kon eventually grew into his own unique voice. His works blurred the lines between dream and reality, and played with non-linear storytelling, to construct thought-provoking tales unlike anything that had been done before. No matter how fantastical or haunting his films were, they remain rooted in a certain level of identifiable reality. As the documentary explains, Kon put himself and the issues he was dealing with in every film. His debut film Perfect Blue (1997) is as much about Kon’s conflict with the animation industry as it was a dark commentary on Japan’s obsession with pop idols.

Vincent’s film occasionally shines a peering investigative light on Kon’s murky relationship the Japanese animation industry but leaves it up to the audience to pick up the sparse breadcrumbs of clues in the fog. What is clear is that Kon was actively trying to change a culture that valued financial success, like Studio Ghibli achieved, over ground-breaking artistry as a gauge for who was worthy of respect. His films may not have been box office hits, though all were critically lauded, but Kon pushed himself, and those he mentored, to think beyond the standard fare of animation with cutesy characters.

Pushing the envelope on what could be achieved in cinema was an essential aspect of Kon’s filmography. His masterpiece Millennium Actress (2001), which is a vibrant ride through Japan’s cinematic history dating back to the early propaganda films, single-handedly inspired a generation of creatives to produce more challenging works. Even his more playful films Tokyo Godfathers (2003), whose premise was inspired by works like John Ford’s 3 Godfathers (1948), and his biggest hit Paprika (2006), a mind-bending work that he thought would be his “Sailor Moon” style fluffy commercial film, were operating on levels deeper than their simple premises would lead one to believe.

Although Kon’s films frequently strove to break new ground, the same cannot be said for Vincent’s documentary. Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist plays it surprisingly safe considering the visionary man it profiles. The awkward use of narration to introduce each of Kon’s films gives the documentary an academic feel that Vincent never fully commits to. Even some of the visual aesthetics employed, while interesting at time, lack the overall punch needed to set the film apart from other documentaries about filmmakers.

Where Vincent’s film excels is in the wealth of intriguing insight that the interviews within it offer. They paint a fascinating portrait of Kon as a man and an artist. He was a genius whose gentle and compassionate persona in real-life was vastly different from the forceful, and at times disturbing, works he produced on the screen. Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist works best when viewed as a tasty appetizer that whets one’s appetite for diving into Kon’s meaty canon of films.

Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist is available on demand at the Fantasia Film Festival from August 5th to August 25th.