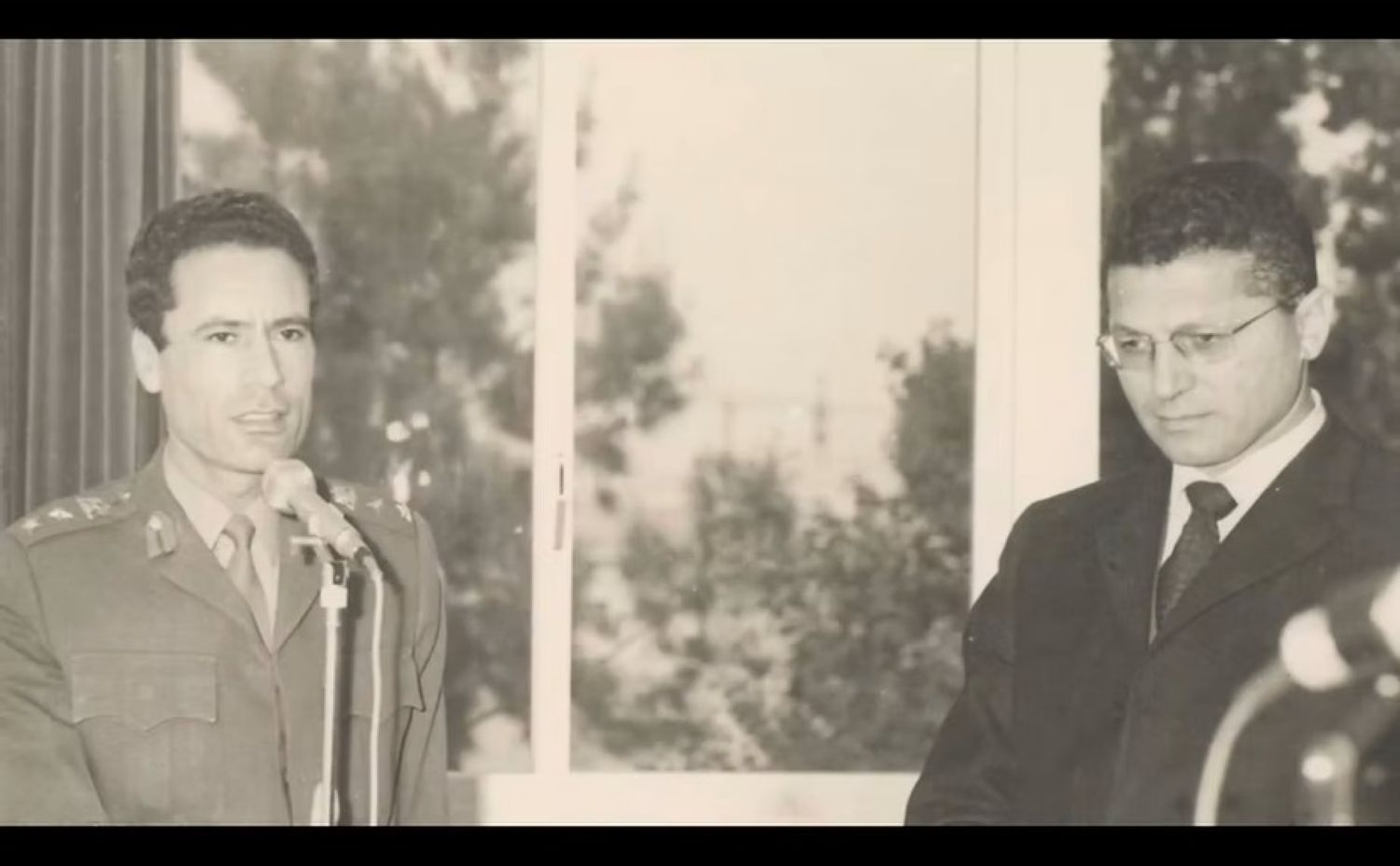

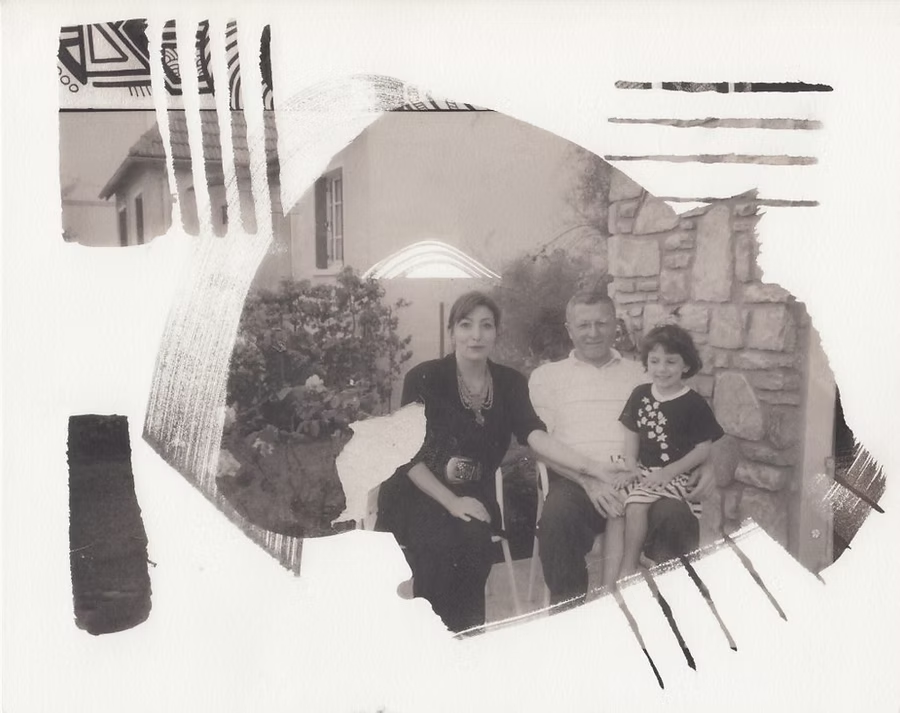

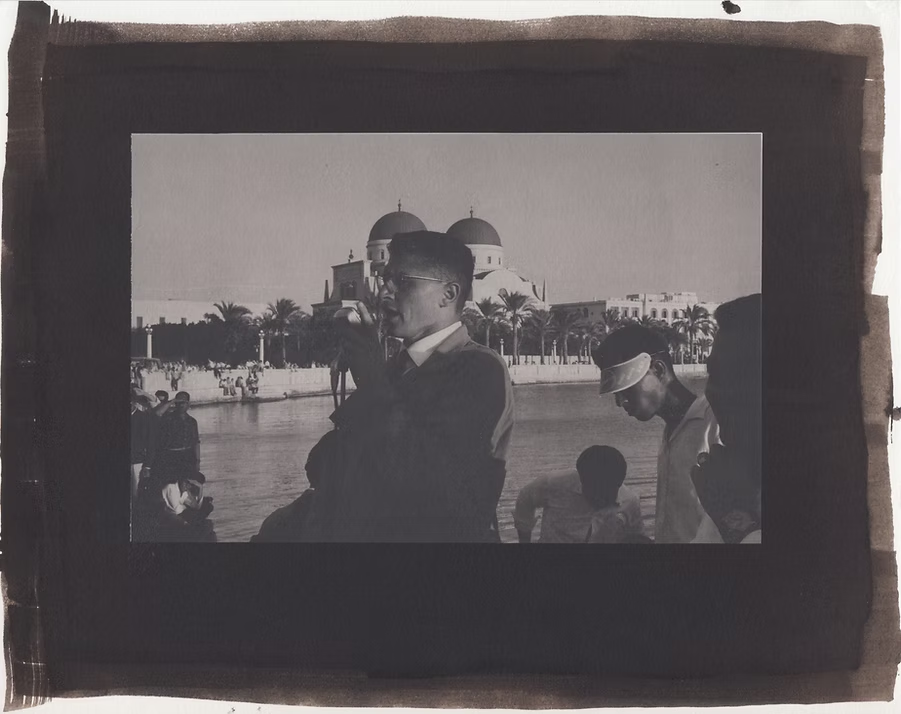

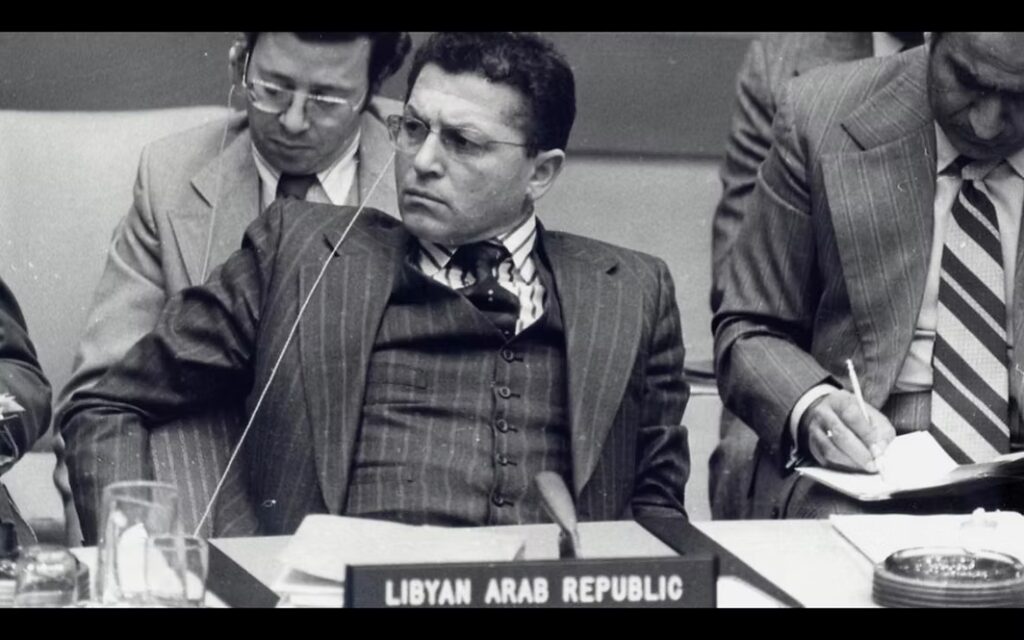

On December 10, 1993, Mansur Rashid Kikhia was abducted close to his hotel in Cairo. The former Libyan diplomat and Minister of Foreign Affairs was originally a staunch supporter of the nation’s long-time leader Muammar al-Qaddafi. Kikhia left his position within the regime and soon became an outspoken opponent regarding the direction in which Libya was headed socially and politically. He was in Egypt to participate in a conference on human rights, having left his wife and children back in Paris with assurance that all would be fine if he travelled back to the region.

He never came home.

This is the backdrop to the greater story captured in My Father and Qaddafi, director Jihan’s subtle, moving, and powerful film that tries decades later to emotionally and historically contextualize how this experience at six years old shaped her and her family. Yet the film is not myopic in its scope and avoid being a mere investigation of personal trauma. Instead, it is a broader look at the complexity of political alliances and the rules of politics that often have fatal consequences, with the cycles of generational trauma simply being the most overt of the scars left behind.

Jihan’s first film is an exercise in creating an accessible yet probing look at the circumstances surrounding her father’s disappearance, her mother’s tireless activism for answers, all while illustrating that knowledge may partly set one free , but it certainly doesn’t necessarily provide full levels of catharsis or closure. While the film’s title obviously alludes to her father’s legacy, the film is as much if not more about her mother’s resilience and the impact that her actions had on the children she raised who would then grow up to help tell this story in a way that can reach people from all over the world.

POV spoke with Jihan following the film’s premiere in competition at the 2025 Marrakech International Festival, mere hours before it was crowned the Jury Prize winner by its prestigious jury headed by Bong Joon-Ho.

POV: Jason Gorber

Jihan: Jihan [who prefers to be credited by her first name only]

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: What do you remember about your father before the disappearance?

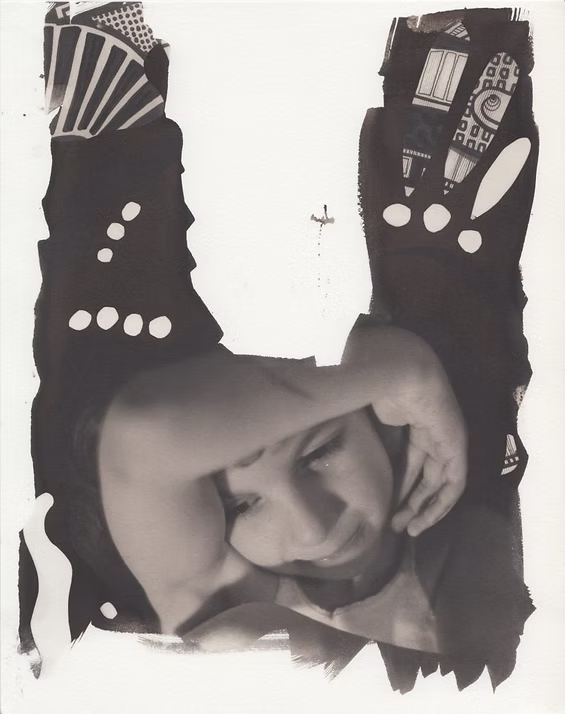

JIHAN: My father, to me, is locked away in a dream world. I know he exists, but I don’t have very many memories of him. The ones I do have are like fragments and whispers of the life before. There are some concrete sounds that I’ve chosen to believe are associated with him. There’s the sound of slippers walking through the house. There are stomach sounds, and his heartbeat. In the photos, it’s shown that I spent a lot of time on his chest. Chess always reminds me of him, a chessboard always reminds me of him. Certain photos have reinforced those memories for me, so I’m not sure if those memories come out of them.

POV: What is the earliest memory you have of understanding your father had disappeared?

JIHAN: I don’t have a memory of that. There is no marked time. I don’t remember it, but I must have been told.

POV: There may have been some effect that you recall. Did teachers treat you differently? Did fellow students make fun of you? There could have been both calm and darkness.

JIHAN: Very good point. Interestingly, the trauma of my father disappearing is actually completely tied to location, identity and language for me. My father was kidnapped December 10, a few days before Christmas break for primary school. I was in first grade in France. I was Francophone. I had lived in the same neighbourhood, and waited for my father to return to the same neighbourhood in the same house I had lived for all my life.

He disappeared that Christmas, and I was in the United States by the first week of January. I never got a chance to see how I would have been treated differently, to measure what had happened in my life. I have triple layers of trauma because I was also immediately displaced and moved to a country that I didn’t know. I didn’t understand, and didn’t speak the language. I moved to a different home and I was torn away from my mom. In my child’s mind, I probably felt like I’d lost both of my parents at the same time.

POV: Your mother’s background is Syrian, but she’s American citizen.

JIHAN: She’s naturalized.

POV: And so you went to the United States to live with relatives?

JIHAN: Yes, my eldest half-sister. In my mind, when I spoke French and lived in France, my father was alive. I was forced to become Anglophone within two weeks. If I spoke English and was in the United States, and thus my reality was that my father was kidnapped. So, while I don’t remember being told, my life completely changed.

POV: When did you become a storyteller?

JIHAN: [Laughs.] I don’t consider myself one. My mother’s a storyteller. Maybe if I hadn’t made a film it wouldn’t be obvious that maybe I had inherited some of that too. There’s a style of talking and engaging with the world. That’s how I saw my mom engage with the world, and engage with me. One of the ways that I engage with people is through stories, especially humour, exaggeration, painting pictures, theatrics. It’s all a bit of theatrics.

POV: But you seem to have known for many years now that this was always going to be a film. What is the process from this being your story, to being a story that is to be told?

JIHAN: When the world around me changed, I felt a shift in my sense of responsibility and the urgency. Suddenly, my life went from that part being very compartmentalized and dormant, the Libyan part is this mythical part of my life that’s compartmentalized.

POV: Libyan by blood, but you’ve never lived in Libya.

JIHAN: No, [when] I was born, my father was already exiled, so I was already displaced from it. It was far away, and it was led by terror. It’s also synonymous with terror.

POV: You’re not only telling the story of your father, you’re telling your story. Not in some ways, in every way. You’re telling your story, you are reconnecting with, de-displacing those elements.

JIHAN: Correct. I’m now an adult with these fragments, with this kind of shattered, fragmented identity. I asked, which one of them will have a thread that will take me all the way back to the beginning? The film was trying to take me all the way back 100 years. That was the thread I was trying to find that would then connect me to my father, to my father’s country.

POV: How did you deal with telling this story without re-traumatizing yourself?

JIHAN: If anything, if I’m inviting any new terror into my life it would be after the film is released. It now depends upon who I share it with, and how people react. I’m not sure how the Libyan demographic will truly react on the ground. Have I poked a bear? That’s not my aim, but there’s a risk.

But no, it’s the opposite of incurring trauma. This was something I had to do. There was an urgency. My father disappeared once when I was six years old, and there was an opportunity to not have him disappear twice. 25 years old and six are very different. I’m an adult, I understand the context. I’m seeing the country fall into civil war again, and there is a new wave of extreme destruction and death, from the Arab Spring to the civil war, where people my age and younger are dying.

So where does my father’s story fit? It’s almost embarrassing to squeeze him in there when now we’re dealing with a new wave of death, a new wave of disappearance, a new wave of trauma. I realized that actually we as a family were holding on to this memory. I thought it was just my mom. I’m sensitive to the fact that if my mom passed or something happened to her, everything she knows would disappear with her. I grew up with [these] stories and I know them, but I could never recount them because I didn’t live them. My memories are formed as a passive observer, in awe. But I’m also detached to survive emotionally.

POV: Your father was obviously your father, but he was also complicated politically, both in and outside one of the most notorious regimes of the 20th century. You were forced with the film to see him not simply as a father, but as a three-dimensional figure of history. That that mental shift happen with this project? Was there a moment in making this film that you realized your father is a cog in a very complicated wheel?

JIHAN: The film didn’t make me realize that, as I grew up with that nuance. My mother raised us to understand that being in the Arab world and being in politics, you’re either a dictator, a King, or you’re subject to being disappeared. The there’s being members of a diaspora and all the layers that this evokes, as you’re in a new home country, a second or third culture. My mother never raised us with this kind of reductive, combative ideology.

She taught us that if you’re going to judge, you judge by people. One by one. Individually, she would tell us, Qaddafi, and my father, they’re both Libyan. One killed his own. You can only blame outside forces so much. You can only blame colonization so much. You can only blame imperialism so much. There’s got to be accountability for your own actions. She was a really big proponent of that, not just in politics. We lived in a home, it was very strong in the spirit of our home, accountability as an individual. You could never go up to my mom and just say I did this because of that. You wouldn’t get away with it.

That was how we were shaped to see. It was very helpful as children because she reduced all of this complexity to individuals caught in a complicated situation. We never got caught up in nationalism, the dogma of religion, the dogma of cultural norms. We spoke Arabic, and had a very beautiful relationship to Islam. My mom would recite text as if it was a philosophical text, very effortlessly non-dogmatically woven in to conversations, to life lessons. We were raised proudly Arab without the nationalism, without feeling trapped to the modern proxy war.

We never grew up with her cursing Qaddafi. We never reduced the regime to bad and my father all good. Actually, the person who was the most critical of my father was my mother! Because at the end of the day, she was his wife. And wives always have something to say about their husbands. [Laughs.]

POV: It’s clear that this is very much her story too.

JIHAN: When growing up my mother did a clean divide between her mission and her responsibility as an adult as the wife of this man to look for him, and to mother his children. She allowed us to have a childhood, and she invested in our joy. It took 19 years to find him. She should have been widowed from the beginning to also be liberated, in a sense. It’s not like someone was on the other side waiting and judging us to see how miserable we were, to perform grief, to perform. She would tell us in her own way, it’s not your fault your father is Libyan. It’s not your fault your father was in politics. That’s his past, his destiny, his choice. Not the injustice. That’s still injustice. And that’s why we’re fighting for him; that’s not your fight.

POV: He could have stayed in Paris.

JIHAN: She told us things like that.

POV: But he couldn’t have stayed in Paris and still been who he was.

JIHAN: That separation of my mother as Baha, my mother as an individual, as a person, and then her [nature] as a dutiful mother protecting us, was actually a very clean divide. I would look across to see the world that she was fighting. My mother would put armour on, go out to war, and come home and make us dinner. My relationship to her and filming her was a very natural extension of the objective lens I have of my mom. I know that objectively this is remarkable, what she is doing. But she was different with us as a mom. She was just sweet and kind and she understood me. I felt really seen by her, I was very free. She gave me a lot of gifts that are essential tools to surviving life, whether or not your father has disappeared.

POV: What was it like going to Libya?

JIHAN: I’ve been going there since I was 10, so I’ve been through many different eras and phases.

POV: You had a sense of terror and anxiety going there?

JIHAN: Yeah, but then I also really weirdly felt safe, [in the company of] both in my mom and Qaddafi’s men. It was weird.

POV: Did you meet Qaddafi?

JIHAN: No, I didn’t meet him, but I met a lot of higher ups. I was always hiding behind my mom’s leg and I was just watching [when I visited as a child]. I watched a lot of conversations growing up. I watched my mom have different variations of conversations with Qaddafi that she had with other men. I was there. I saw it all. I saw the double talk. I saw the appeal without accusation. I saw the diplomacy, the asking for help without victimizing. She did a lot, and at the same time and yet we still had an appetite, we still ate meals, went to bed, were good kids. I think she made me feel protected, she made me understand. Like I said, this was her fight.

POV: Qaddafi is one of the giant historical figures of the 20th century. What is something about him that she, as a human and as a woman talking to the man who inevitably had a role in killing her husband, has told you about, him?

JIHAN: She has, so we could do a whole film on it. I think she has a really fascinating breakdown of the psychology and how she found strength in the truth, and he may be extremely powerful. He has all of this superficial apparatus of power, but she’s talking about inner power, inner truth, she had that. She knew she was innocent. She knew my father was worth fighting for. And also, an injustice was committed.

She did mention that he was oddly polite, he was a good listener. It was actually the men around him in the tent that had more extreme behaviour, but maybe they were also reflecting the terror and the fear. They had to perform their allegiance to Qaddafi. Her ability to keep a conversation with him for an hour is pretty remarkable. She was talking about children, talking about life, talking about dreams, just trying to humanize him without attacking him. It’s a very interesting choice. Interestingly, I don’t remember her [absence] in my life. I remember she was always there. Now that I’m older, I’m like, how did she not just collapse into bed and give up for at least a week to recover from Libya? I just remember her always around. She never missed a meal. It’s incredible, so she had that security and stability, she maintained that in my life.

POV: Do you look at your father’s disappearance as the beginning of cynicism or do you look at the current situation or your mother’s behaviour as a beacon of hope?

JIHAN: They both represent hope. And they both represent courage.

POV: Your father still represents hope, even though overtly it is a strong indication that, one could from the outside see it as him either looking for martyrdom, which I don’t believe is the case, or him not truly believing that something like this could happen to him. But equally, one would think that he would not have “abandoned” his family without deeply feeling that while it happened to other people, he believed it would not happen to him.

JIHAN: When someone fights for what they believe is a better life, for something good, something they believe is good, I know that being good and bad are much more nuanced concepts. But just for the sake of being simple, when you know that this person has suffered or sacrificed their life knowingly or unknowingly for that, something in you allows yourself to rise to the occasion of being good in life too. So I may not be able to be a lawyer or an ambassador or fill any of my father’s footsteps, but I can invest in trying to be good as well, because then that passes on to everyone around you.

That’s all there really is in life. The goal is to provide a soft landing, empathy, kindness. Everybody’s dealt with challenges, which is what my mom taught us. Thankfully, she spelled it out quite clearly, so that we didn’t unnecessarily suffer, but we had our own challenges as well. To me, they both represent courage.

POV: Earlier you were talking about your appreciation for O.J.: Made in America. You only knew him as a murder suspect?

JIHAN: For me, to watch that film in my 30s, that docuseries was fresh. I only knew the murder and that’s not much. They did a brilliant job of understanding a little bit of his emotional past and his childhood, how all of these could suddenly build. By the end, you’re right down the middle. You can understand the riots, because there was enough buildup to understand the context of America at that time, but then you can also understand the blatant absurdity and injustice of it all. I think a topic that hot, so much attached to it, and so raw, and the timing of when it came out in the US, that’s where I saw an example of how it can work.

I tried to be really down the middle and very subtle. I tried not to veer off too evil with Qaddafi or too perfect with my father, The more you give context, the more there’s the gray, there’s the ambivalence, the nuance.

The industry told me that I am the main character of this story, and I had to say, “It’s not therapy.” Even just restructuring the story with the way I see the little girl at six years old at the center of it, that’s life changing for me. Even if I didn’t ever end up making the film.

When my father was kidnapped, The Lion King came out. I used to go into this deathly silence when Mufasa was killed. I love children’s stories. I want to say another compliment to my mom because she told me age-appropriate information from such a young age. I’m both a recipient and also an observer of how she got to the essence of what happened. When I started to make my film, I thought, “Oh, my God, I’m going to have all of these massive breakthroughs.” In actually it’s like in The Little Prince. I started out with the rose. My mother had already told me the essence. When you already have the essence, the rest just becomes decorative and flavours. My father’s life is intricately tied to Libya’s history. We’ve done 100 years because of his age, but I just went back to me and him eating croissants.

POV: And you staring into the camera. Inviting us in.

JIHAN: I treated the audience as intelligent and empathetic, without losing the essence of The Lion King or The Little Prince. We can [as] a child, a young adult, anywhere in the world, use our hearts and human connection to understand what happened to my family and follow all the way to the end. In the end, we can have a more human connection, empathetic connection to Libya, to the Libyan people. That to me, is a political act against what Qaddafi has done. It’s my way of saying, I know you’ve done things for the reasons that you did. I tried to understand it as best I could, without over justifying, rationalizing, or disrespecting those who have died and suffered. But he is not allowed to take away our whole history and identity. This is my way of saying, there was a Libya before; there was a life before. It’s the past, but knowing that it exists is a way of giving us a little bit more power to reimagine ourselves today.

It’s simple. As a child. My mother was able to tell me information I was able to handle emotionally, the same was The Lion King could. There was a death. And it’s terrifying. But you follow and you have fun and you fall in love with this film.

POV: Hakuna Matata.

JIHAN: [Laughs] Hakuna Matata!