“Mostly, I see what isn’t working. Then I tell myself to look at what is working and snap out of it,” Karen Kain, former ballerina and National Ballet artistic director, admits after a tense moment in Swan Song. “I’ve always been at the side of the choreographers who came to work with us. I’ve never been responsible for it before, and that’s a big difference.”

Kain’s remarks come days before the premiere of her directorial debut with Swan Lake. The rehearsals are pretty bumpy. Kain is butting heads with her Swan Queen, Russian–Lithuanian ballerina Jurgita Dronina, who questions her judgement before the cast and crew. Moreover, the production marks Kain’s retirement

from the National Ballet of Canada after five decades with the company, including countless performances as one of the most acclaimed ballerinas worldwide.

Swan Song, which premieres at the Toronto International Film Festival, chronicles the artistically dazzling and frequently chaotic production of Kain’s Swan Lake. Directed by Chelsea McMullan (Ever Deadly, 2022), written/produced by Sean O’Neill (In the Making, 2018), and featuring a who’s who of executive producers including Jennifer Baichwal, Nick de Pencier, and actress Neve Campbell (a trained dancer herself), Swan Song offers a vérité portrait of the sweat, tears, triumphs, and many Advils entailed in mounting a ballet. The documentary, which will also play as a four-part series this fall, follows Kain as she remains cool while dealing with COVID-19 delays, a diva ballerina, elaborate trip hazards from the costume department, and exhausted dancers who run five kilometres during the fourth act alone. Kain’s reputation is on the line here after a lifetime devoted to ballet, which makes Swan Song an artfully anxiety-inducing backstage drama.

Taking flight

Kain’s production draws upon Erik Bruhn’s acclaimed staging of Swan Lake, which she danced at the beginning of her career with the National Ballet at age 19. Beyond refreshing one of the company’s beloved interpretations, Kain injects Swan Lake with a feminist perspective. She sees the dancers as women breaking free from the shackles of the male gaze. Her revisionist take doesn’t come easily, though, since Swan Lake brings the baggage of familiarity. It’s the ultimate artistic test to make one of the most widely performed ballets feel fresh.

Everything points to disaster, but Kain trusts her gut. She knows Swan Lake, having performed the dual role of Odile and Odette many times. A sumptuous tapestry of archival reels and photographs conveys the range of roles that Kain has danced. The sheer scale of the archival work interweaved with the vérité footage illustrates Kain’s contribution to dance over half a century. The film observes Kain’s mastery of the art and willingness to push herself as she listens to collaborators, like choreographer Rob Binet, and takes feedback. She’s determined to let the ugly duckling flourish by opening night. It’s clear why she’s internationally renowned as a dancer and how she managed the National Ballet for 16 years as artistic director. But that could all end with a bellyflop.

“It’s something we were talking about the entire time and it felt like a real possibility at certain points,” says McMullan on the potential for the show’s failure. “This was the most ambitious production in the history of the company, so the pressure, the scale—everything was exponential, but we were committed to seeing it through. Whatever happened, happened.”

Curtain call

“We were shocked when it came together so beautifully on opening night,” agrees O’Neill. “It’s a cliché in theatre that

it sometimes comes together, but sometimes doesn’t. The filmmaker in me was like, ‘If it doesn’t come together, we’ll have an interesting ending.’ But the producer in me was like, ‘I really hope it comes together because we want a great opening-night scene.’”

The opening-night sequence is a triumph. Lensed by cinematographers Tess Girard and Shady Hanna, Swan Song creates an invigoratingly cinematic rendering of the production that gives viewers all the best seats in the house at the Four Seasons theatre in Toronto. One feels the well-earned collective sigh of relief once the final curtain falls and the applause roars.

“We did not want it to feel like a live capture of a ballet,” says McMullan. “You want the essence of what it’s like to watch Swan Lake, rather than literally capturing it. The experience of watching it doesn’t translate in the same way.” From Kain’s anxious perspective amongthe crowd to the dancers enjoying the show in the wings, Swan Song delivers an immersive portrait after the fashion of dance docs like Jody Lee Lipes’ Ballet 422 (2014) and Frederick Wiseman’s La danse (2009).

Learning by doing

Swan Song draws from a whopping 450 hours of footage to create this all-eyes perspective. It builds upon the sensibility for documenting dance that McMullan and O’Neill honed in their 2022 doc Crystal Pite: Angels’ Atlas. That film arose during the production of Swan Song when the duo, having told Pite’s story in an episode of O’Neill’s series In the Making, were asked by the choreographer to record her 27-minute contemporary dance production with the National Ballet after a French team fell through. Angels’ Atlas was commissioned as a live capture of Pite’s performance in full, whereas Swan Song chronicles the makings of Kain’s final run and would need a Wiseman-esque running time for the same feat.

“It was a coincidence that Crystal asked for us when we were developing this project,” says O’Neill, “but it ended up being incredibly useful from a production standpoint because we learned how complicated it is to shoot in these venues and we built trust with the company.”

“We saw an amazing opportunity to teach ourselves how to shoot Swan Lake. We obviously treated it like its own project, but we learned so much that could be applied to Swan Song,” adds McMullan. “I love the challenge of representing an art in another format through cinema. I’m a visual person and my entry point is asking how we use cinema to visually capture another art form.”

Capturing the shows

The production certainly benefitted from the run the team had with Angels’ Atlas. “We had a lot more freedom with Angels’ Atlas in the sense that we shot the performance live and then were able to shoot an additional two days with the dancers on stage where we had both a Steadicam and a Technocrane,” explains McMullan. “I shot-listed that whole performance.”

When it came to Swan Lake, however, McMullan’s team only had one go with a live performance, coupled with additional time filming backstage shots and rehearsals. Eight cameras captured the live show with McMullan calling shots from a booth.

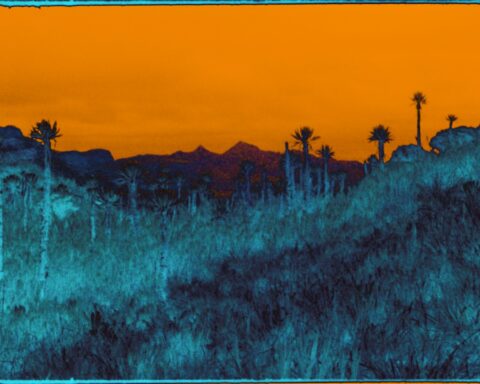

Photo by Christopher Sherman

Other cameras were backstage to record the juicy drama and comments from the ballerinas.

“The language is quite different between the films because Swan Song is about watching the performance and it’s very exciting to see, but it’s also about being with the dancers backstage, feeling the environment, and seeing our characters performing it,” notes McMullan. The “opening night” scene of Swan Song includes portions from a dress rehearsal shot in full for the proscenium angle. Cable-cam shots recorded during the dress rehearsal let the doc flap its wings without obstructing the views of patrons who coughed up Hamilton-level prices for the ballet.

Under Kain’s wing

The doc also capitalizes on the dramatic buildup to opening night and the process of finessing an artistic vision. “We tried a million different versions of the opening-night sequence and then finally we were like, ‘Oh, it’s a battle scene,’” explains O’Neill. “We had to be up close with our characters and then scale back to see it. There needed to be this driving momentum and arc with a deeply felt, character-based emotional journey. Great battle scenes bring you incredibly close to your heroes, and then you can see the spectacle.”

The battle is twofold. On one hand, it’s a fight for Kain’s legacy as creatives reconcile their differences and trust the master’s vision. On the other, the company’s future needs a smooth transition. Kain’s retirement marks a major passing of the torch not only for the National Ballet, but also for Canada’s dance scene as a whole. The future of the ballet looks promising, though, as the dancers and choreographers are well prepared for a post-Kain company.

Drawing inspiration from the Netflix series Cheer (2020–present), which follows a team of cheerleaders, the filmmakers say they envisioned the story as capturing an ensemble. Swan Song gains additional insight from Dronina, who is dancing Swan Lake for the 10th time and, under Kain’s direction, unlearning all that she’s done before. She dances beautifully on opening night, all tension with Kain seemingly resolved. Meanwhile, dancers Shaelynn Estrada and Tene Ward represent the corps—the ensemble of the ballet—along with choreographer Rob Binet and young dancer Genevieve Penn Nabity, who plays Odile/Odette on alternating nights and aligns more closely with Kain’s vision than Dronina.

In a tight spot

These perspectives beautifully illustrate the creative pressures within a field reared on “been there, done that” Swan Lake. Beyond injecting the ballet with a feminist perspective, Kain shakes things up by suggesting that the corps not wear tights. The company, like many organizations post-2020, confronts the racial inequity in its history. Kain acknowledges that she can’t stage Swan Lake with a contemporary sensibility while using costuming that doesn’t match dancers’ skin tones. For Ward, who paints her slippers brown to reflect her mixed Sri Lankan, African American, and Cherokee heritage, the gamble is refreshingly overdue. For Estrada, however, nude legs invite nerve-wracking vulnerability. Taking the stage without tights, she reveals fresh scars on her legs. As Estrada tells the camera, she sometimes feels alienated as a queer performer. The film also gives Estrada a personal interlude in which she explores her mental health struggles through dance.

Besides bringing the company back after COVID-precautionary closures, Kain’s had to shoulder the responsibility of making the ballet relevant. But she’s smart enough to keep the filmmakers at a distance when talks about tights become tense. (Who knew tights could inspire such riveting drama?) In one of Swan Song’s most telling moments, Kain side-eyes the camera and murmurs to her colleague that they’ll chat later when nothing is rolling. Achieving international stardom inevitably entails a lifetime of media training. The ensemble raises issues that the well-spoken Kain often avoids. She’s candid when she needs to be, but chooses her words wisely.

Incubating the eggs

“We were upfront with Karen that we weren’t interested in making a filtered tribute to her legendary status,” explains O’Neill. “That’s not for a lack of admiration, but a desire to get at something deeper, not only in her arc, but also in the arcs of the other characters and in this look at the world of ballet. I think the artist in her found that very appealing. She was willing to talk about her personal struggles, her anxiety, and the fact that the production wasn’t coming together.”

McMullan adds that they were able to get more from Kain thanks to the longitudinal nature of the project—three years—and their immersion in the company across two docs. “Our goal was to build a dynamic so that when we got into the thick of things, it would feel like we were one entity with the ballet,” says McMullan. The director says they had frequent conversations about comfort levels and won the ballerinas’ trust enough to be permitted to affix microphones on each of them. Throughout rehearsals, the mics catch some great verbal eyerolls that evoke passion and frustration in equal doses.

“No one wanted to be mic’d and this is a really intense culture where they can’t start late, but it takes a second to get the microphones on,” laughs McMullan. “We had endless discussions about these microphones. Then they didn’t want us to be so close with the cameras. But through repetition, through being there, we shot every single day and inched closer and closer and closer. They felt more comfortable being themselves and having conflict. That came through shooting so many boring-ass rehearsals where nothing happened so that we could get that level of intimacy.”

Expanding the cast—and the canvas

McMullan adds that their immersion with the dancers began in the earliest stages. They interviewed all 70 dancers in the company over Zoom to find the right characters after researching key players on social media. Other performers who appear briefly in the feature get more airtime in the lengthier TV series. Among them is South African principal dancer Siphesihle November, one of six ballerinos cast as Siegfried, and Argentine ballerina Arielle Miralles, an apprentice who lands a job in the corps. Other topics, like the costumes (a sticking point even in the most positive reviews of Swan Lake), get deeper dives in the series, but the feature nevertheless captures the collective effort to fulfill Kain’s vision.

“What unites our characters is that they are fighting to get to this impossible ideal in ballet that’s wrapped up in athleticism, skill, and artistry, but is historically wrapped up in whiteness, in a certain body type, and in performances of gender,” notes O’Neill. “As the world changed, we found so many people in the company who felt a profound struggle to try to reach that ideal. The characters that we zone in on are the ones who had something powerful to say about the impacts of this culture, why they love it, and why they fight for it.”

Photo by Karolina Kuras. Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada.

Everything comes together

The filmmakers add that exploring two formats was a rewarding process that we’re likely to see more of. (Canadian dramas BlackBerry and Bones of Crows were both released this year in feature-length and series versions.) “We pitched this as a series and it quickly became clear that we would have to cut a feature in order to achieve financing,” O’Neill says. “The idea interested us creatively because they’re two completely different languages. From a craft perspective, it’s an amazing opportunity to take 450 hours and put it into one format and then put that same material into a completely different format.”

While Canadian filmmakers habitually have to compromise their features to make CBC’s 42-minute broadcast slots, Swan Song’s full canvas mirrors Kain’s effort to leave a mark with something new. “We saw it as an opportunity to hone our craft and understand the language,” says McMullan. “You make this film and then you interrogate your entire process. It takes stamina to do them as separate creative entities.”

Fortunately for Kain, her legacy as one of Canada’s greatest performing artists is upheld by the stamina she displays throughout the production. Once performances are over, McMullan joins Kain as she combs through a box of press clippings left at the company. The usually guarded Kain displays great vulnerability as she recognizes a career coming full circle, knowing well that some dancer in the company, perhaps the next Karen Kain, has experienced the same emotional rollercoaster with Swan Lake.

“Sometimes afterwards you can say, ‘That was a really good experience and I really enjoyed it,’” an emotional Kain says, reading an interview she gave at age 27. “But you’re concentrating so hard on what you’re doing that the only time it’s ever really fun is when you’re feeling no pain and things seem to be going well.”

Kain pauses, looking over the articles and photographs that summarize her remarkable career. Suddenly, poignantly, it all hits her.